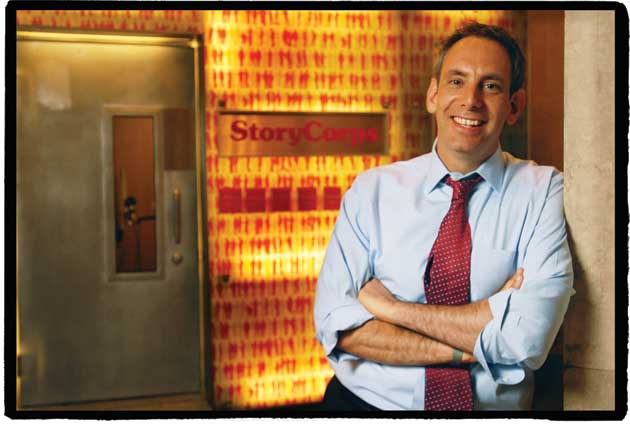

Dave IsayCourtesy Harvey Wang/Storycorps

Radio producer Dave Isay first made his mark with stories like Ghetto Life 101, for which he enlisted a pair of precocious eighth-graders to document their lives in a Chicago housing project. He saw how putting the kids in charge of the recording gear gave them license to ask questions they might never have asked otherwise—and how the mere act of participating in these very personal interviews “could transform people’s lives.”

In 2003, he launched a project called StoryCorps, setting up a booth in New York City’s Grand Central Terminal where anyone could walk in and interview a relative, a friend, or even a complete stranger for 40 minutes. The project’s mobile recording booths have ambled through 174 American cities to date, helping collect more than 50,000 interviews involving 90,000 people. The recordings are archived in the Library of Congress, and choice bits are broadcast weekly on NPR’s Morning Edition. For its 10th anniversary this month, StoryCorps is releasing a greatest hits book, Ties That Bind, and throwing a gala hosted by Stephen Colbert.

StoryCorps has also launched initiatives to capture the voices of special demographics: ethnic minorities, teachers, seniors, people with memory loss, even one dedicated to preserving Alaskan heritage. The archive is a paean to unsung heroes—people like Ted Weaver, a janitor and chauffeur in pre-civil-rights era Knoxville, Tennessee, who stayed up late to teach himself algebra so he could help his son Lynn with homework. (Lynn tells of his father’s modest feats in a recording embedded in the box above.)

Isay, the recipient of six Peabody awards—radio’s highest honor—and a MacArthur “genius” grant, calls these recordings “poems of the human voice,” but artistic merit is hardly the point. “People know that their great-great-great-great-grandkids are going to get to hear their voice someday, and this will be maybe the only thing they leave behind,” he told me recently. “There’ll be pictures and other things, but the soul is contained in the voice.”

Mother Jones: I’ve read that StoryCorps was inspired by the oral history projects that came out of the New Deal.

Dave Isay: I used to go to the American Folklife Center in DC and listen to those interviews. There may have been less than 100 recorded on these discs—a bunch of them by John Lomax. I remember a recording of guys in a pool hall right after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and you can hear the balls, people shooting pool in the background and these guys, very beautifully and clearly recorded, talking about about what was about to happen. It just kind of transported me back in time.

MJ: I gather some academics don’t consider StoryCorps true oral history?

DI: Yeah, I think because the people who are asking questions aren’t academics, and there’s a time limit. And that’s fine. We feel like we walk in the footsteps of oral historians and Studs Terkel, who loved StoryCorps! I’m not so concerned about what people call it, I’m just kind of concerned that people take the time to have these conversations.

MJ: Did you set up StoryCorps this way in the hope of eliminating the biases an outside interviewer brings into the process?

DI: No. It was more that when you’re interviewing someone whom you know very well, you have so much more at stake. That was kind of the electricity.

MJ: As more people hear these pieces, have you run into problems where people try to tell their stories similar ways?

DI: When it started, I didn’t think there was going to be a broadcast component because I thought stories were going to start to repeat, and because I figured there were a finite number of interactions that a grandparent and a grandkid could have. One of the many miracles that StoryCorps has had is that the stories have not only not repeated, but they seem to get better as time goes on. There are all these stories about love and birth and death. But the variety and the scope and the power of the stories that come out of these themes never cease to amaze me.

MJ: You’ve always been interested in voices on the margins. What have you done to ensure that a wide variety of people take part?

DI: Half of our slots are for the general public. The other half we call “outreach” interviews, where we partner with nonprofits—they suggest their clients go into the booths to record their stories. I think the power of the StoryCorps interview is that having someone listen to you in this quiet booth and asking who you are and how you want to be remembered tells people that they matter. A bunch of years ago on the Bowery, I did a radio documentary and a book about guys who lived in these prison-size cubicles with chicken wire on the top. I remember bringing the galley up into one of the flophouses and showing it to one of the guys who was in the book. He stood there for a couple of seconds and then he yanked the book out of my hands and he started running down the hall with the book over his head shouting, “I exist! I exist!”

MJ: Do certain geographical areas have a disproportionate number of great storytellers?

DI: There are sweet spots. Like Rust Belt towns, industrial towns that are having a rough time—people who feel like they don’t matter so much.

MJ: Can you talk about some of StoryCorps’ specific initiatives, where you focus on certain groups, like the families of veterans, or African Americans.

DI: Our current one is post-9/11 military and their families. The next one we’re going to launch, in June 2014, is called Out Loud, and it’s LGBT folks across the country. It’s going to focus on making sure people who lived before Stonewall have a chance to leave a record of their lives. And also memorials to people who died before the AIDS epidemic. But there will be people who lived outside of San Francisco and New York, in smaller towns in the South and so forth, to get the full panoply of voices and stories out there.

MJ: Is there any demographic you’ve found especially hard to reach?

DI: If you were going to do interviews in a penitentiary, it takes a lot of work and a lot of planning. But everyone wants to participate. Alex Kotlowitz—a great guy who wrote There Are No Children Here—and I were talking about this idea that you’ll do an interview with someone, specifically people who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan, and it’ll be this very powerful story. At the end, you’ll be like, “Have you ever told this story before?” And they’ll say no. And you’ll say, “Why?” “No one ever asked.”

MJ: Was Ghetto Life 101 inspired by Kotlowitz’s book?

DI: I wanted to do something that was based on the book in spirit, but it was not the same kids.

MJ: How did you find LeAlan Jones and Lloyd Newman, your young producers-slash-subjects?

DI: I sent out faxes and letters to social services agencies and schools all over Chicago for suggestions of kids who were atypically eloquent but lived in typical situations—able to verbally and vocally talk about their lives in self-reflection. One of the people who wrote back to me was [Secretary of Education] Arne Duncan’s mom actually, and I didn’t make the connection until a year ago, but I remember the letter. She said: “I have 28 kids in my class and told them what you were doing and asked if they wanted to be a part of this, and 28 hands shot up.”

MJ: Now that you’ve reached 100,000 participants—what’s it going to take to get to 320 million?

DI: We’re just getting started! It’ll be a long time until we get into the millions, but I think it’ll happen. We will be able to turn this into an institution long after we’re gone, and people won’t necessarily understand what this archive contains for hundreds of years from now.

MJ: So, what’s in the future for Dave Isay?

DI: A lot more hard work, hopefully—StoryCorps is the hardest thing I’ve ever done. And hopefully being a good dad. I have two kids at home.

MJ: Have they interviewed you for StoryCorps yet?

DI: They’re too young. I have a five-year-old and a two-year-old. StoryCorps doesn’t really work until you’re 10.