Patrick Pizzella and his former boss Jack Abramoff.Mother Jones

Update: On July 12, President Donald Trump announced on Twitter that Secretary of Labor Alexander Acosta will be replaced on an acting basis by Deputy Secretary of Labor Patrick Pizzella. As Mother Jones reported after reviewing hundreds of pages of billing records and emails, Pizzella worked in the late 1990s with disgraced lobbyist Jack Abramoff to promote a sweatshop economy in the Northern Mariana Islands, a US territory.

This story originally ran on August 22, 2017:

There’s lobbying, and then there’s working with Jack Abramoff to promote the sweatshop economy on remote Pacific islands. If you want to know about that kind of lobbying, you can ask Patrick Pizzella, President Donald Trump’s pick to be deputy labor secretary. Or maybe you can’t.

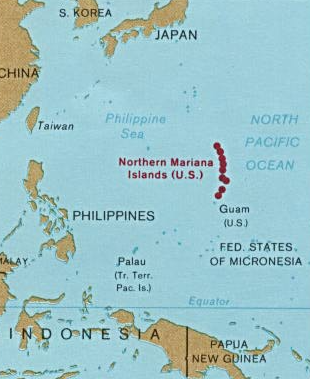

At a July Senate confirmation hearing, Pizzella said he didn’t remember much about the work he did in the late 1990s to help the Northern Mariana Islands—a US commonwealth 1,500 miles from Japan—defeat a bipartisan effort to rein in a guest worker program that the Labor Department found relied on indentured workers. When Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) asked Pizzella whether he knew about reports of forced abortions and routine beatings at the time, Pizzella replied, “I was not aware of any such thing.” Pressed further, he said reports of abuse by multiple government agencies and newspapers were mere “allegations.”

What Pizzella didn’t say was that he helped lead a public relations campaign to rebrand the islands as a paragon of free-market principles. Between 1996 and 2000, emails and billing records reviewed by Mother Jones show that Pizzella and colleagues organized all-expenses-paid trips to the islands for more than 100 members of Congress, their staffers, and conservative thought leaders. When they got back, Pizzella helped them convince colleagues that the Northern Mariana Islands were, as his old boss Abramoff liked to put it, a “laboratory of liberty.”

Now Pizzella is poised to become America’s second-highest labor enforcer. If confirmed by the Senate, he’ll be responsible for holding employers accountable in the Northern Mariana Islands and across the country. (Pizzella, currently the acting chairman of the Federal Labor Relations Authority, a federal agency that handles government employees’ labor disputes, declined to comment for this story.)

Pizzella at his Senate confirmation hearing in July.

Ron Sachs/ZUMA

Pizzella arrived at the law firm Preston Gates in 1996 as Abramoff’s second hire. “Smart, likeable, clever, and hardworking, Pat was a perfect addition to the quickly emerging ‘Team Abramoff,’” Abramoff wrote in his 2011 memoir, Capitol Punishment. Pizzella immediately started reading up on Abramoff’s new lobbying client: the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), a string of 14 tropical islands just north of Guam with a population of about 53,000.

The year before, Abramoff had learned that the CNMI was looking for a lobbyist to fend off increased federal control. During World War II, the islands were under Japanese control until the United States won the Battle of Saipan (the CNMI’s main island) in 1944. After a few decades in limbo as part of a United Nations trust, the Northern Mariana Islands opted to join the United States in 1975 as a commonwealth instead of pursuing independence.

The agreement between the islands and the United States granted two exemptions. First, the CNMI could set its own minimum wage. Second, the commonwealth would be allowed to make its own immigration laws. CNMI officials initially requested control of immigration to ensure that the indigenous population would not be overwhelmed by newcomers. But a decade later, garment manufacturers and the CNMI’s government decided to use the exemption to import unlimited guest workers to make clothes for companies like Brooks Brothers and Banana Republic. The clothes they produced were stamped “Made in the USA” and exported to the United States tariff-free. Between 1985 and 1998, CNMI garment exports grew from almost nothing to more than $1 billion annually—over a third of total CNMI business revenue.

“Things were just completely out of control,” says Allen Stayman, the top Interior Department official assigned to the CNMI from 1993 to 1999. Recruiters illegally required many foreign workers to pay fees in order to land jobs in the CNMI, causing them to go into debt that they’d have to work to pay off. Others signed “shadow contracts” in which they promised their employers not to unionize, date, or practice a religion while working in the CNMI. Some were made to sleep a dozen to a room, with barbed wire surrounding their barracks. If workers complained, the CNMI government, which had close ties to the garment industry, could deport them immediately. In 1992, Willie Tan, a top garment industry baron, paid a $9 million settlement in a Labor Department suit alleging he’d failed to pay workers overtime and the CNMI’s minimum wage of $2.15 an hour—compared with $4.25 elsewhere in the United States. The settlement was the largest in Labor Department history at the time.

When Abramoff signed the CNMI government as a client in July 1995, the US Senate had already unanimously passed a bill to strip the islands of its minimum-wage exemption, setting up what looked to be an uncontentious vote in the House. The year before, representatives from the Interior and Labor departments and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service had testified at a Senate hearing about mistreatment of foreign workers. CNMI Gov. Froilan Tenorio joined them to say he was “disgusted” and “ashamed” by the stories of human rights abuses. “Unfortunately,” he added at the hearing, “they are generally accurate.” Still, the workers kept coming. According to a 1998 federal government report, “indentured alien workers,” mostly from Bangladesh, China, and the Philippines, made up 91 percent of the CNMI’s private-sector workforce. The majority of citizens, on the other hand, worked in better-paid government jobs. Immigration laws that were supposed to protect the CNMI’s indigenous population had made many citizens into overlords who were outnumbered by their guest workers.

A garment factory on Saipan in 1997

Charles Hanley/AP

But Tenorio argued that the CNMI could fix the problems without eliminating the exemptions. Other lobbyists, Abramoff wrote in his memoir, told Tenorio that preserving them was a lost cause. Abramoff disagreed. To save them, Abramoff wrote, he told the governor’s chief of staff that the CNMI just needed to convince the conservatives running Congress that the fight was about defending a free market.

In a 1995 pitch letter to Tenorio, Abramoff argued that personal tours could help sway public officials. Pizzella led this effort. By his second month on the job, Pizzella was spending more than 100 billable hours per month on the CNMI account, about as much as Abramoff. The centerpiece of Pizzella’s work was organizing all-inclusive junkets for members of Congress and their wives, congressional staffers, and conservative influencers such as pollster Kellyanne Fitzpatrick—who now goes by her married name, Kellyanne Conway, and advises President Donald Trump—with first-class airfare and lodging at the beachfront Hyatt Regency on Saipan. “Pat’s very effective,” a former consultant to the CNMI told The New Republic in 2001. “Visitors to the island seemed to get all the right information.”

Pizzella’s first trip, in 1996, included meetings with the governor and the Saipan Garment Manufacturers Association and a tour of a garment factory; some later trips included meetings with human rights activists. Later that year, Abramoff wrote in an email to Herman Guerrero, a CNMI official, that “the recent Congressional staff trips have done more good for the CNMI than almost anything we have done in the past.”

The leisurely aspect of the trips seemed to help. “[S]ome of the group plans to play golf at LaoLao on monday afternoon and Kingfisher on Tuesday afternoon,” Pizzella emailed Guerrero, “please arrange for that authorization letter to the managers at each course indicating we will be renting clubs etc…that worked very, very well last visit.” Another trip included a weekend layover in Hawaii on the way back, according to an email from Pizzella. The New York Times summed up the trips with the headline “They Came. They Saw. They Golfed.”

The view from the Hyatt on Saipan where Pizzella’s guests usually stayed.

After they got back, they wrote. Clint Bolick, a co-founder of the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public-interest law firm, reported shortly after returning that the CNMI boasted “perhaps the most vibrant economy in the United States. The secret: largely unregulated markets that in two decades have created out of almost nothing head-spinning economic growth, productivity, and prosperity.”

Bolick, who is now a state Supreme Court justice in Arizona, and others were particularly impressed that Gov. Tenorio supported conservative priorities like school vouchers. That wasn’t an accident. The year before, Pizzella had discussed vouchers and a flat tax with the conservative Heritage Foundation and the libertarian Cato Institute on behalf of the CNMI’s government. “Our travelers ate this up,” Abramoff wrote in his memoir. “The conservative groups in Washington had found a new hero in this Democratic governor of our least populated territory.”

Another Abramoff tactic, according to a Senate Finance Committee investigation, was to have the CNMI funnel money to a front group, which helped the trips appear independent. Before a 1996 junket, Preston Gates billing records show, Pizzella met with Amy Moritz, president of the National Center for Public Policy Research (NCPPR), a conservative group that funded several trips for Abramoff, to discuss a “CNMI trip and possible funding arrangements.” After he got back, Pizzella explained in an email to Abramoff how a report by Cato fellow Doug Bandow would be paid for. “[T]hat leaves basically the fees for Bandow’s services and report; and the reimbursement for the bills he accumulated,” Pizzella wrote to Abramoff. “…That should come to about $10,000. That is the amount CNMI should provide as a grant to NCPPR. Then they can cut check to Bandow.” Preston Gates billing records include an $8,000 invoice for Bandow’s trip expenses that lists NCPPR as the vendor.

After the trip, Bandow started writing a report for the libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute. Pizzella had about a dozen discussions with Bandow and Marlo Lewis, a CEI executive, about the report, according to billing records. As the publication date got closer, Pizzella, Abramoff, and Michael Soussan, a junior Preston Gates lobbyist, also edited and provided comments on drafts. The final report called the CNMI a “center of policy innovation” and “laboratory of liberty” that could serve as a model for the rest of the country. (Bandow would later lose his position at Cato for accepting money from Abramoff to write favorable op-eds about the CNMI and other clients; he subsequently returned to the think tank and is now a senior fellow there. Bandow did not respond to requests for comment.)

The next year, Soussan traveled to the CNMI with Pizzella, according to his memoir and billing records. As usual, the guests toured a garment factory. “The point of my presence at the scene,” Sousann wrote in the memoir, “was to help these factory owners get away with exploitation.” Without specifically naming Pizzella, he wrote that “Pat, the team leader of the Congressional delegation,” put a different spin on it, saying, “See? Working conditions are not as horrible as the press would have us believe.” On the way out, he recalled, they got a “special treat”: discounted clothes. “The pride I felt for my job at that moment made me want to put a bullet through my head,” Soussan wrote. (Soussan did not respond to requests for comment.)

When Stayman, the Interior Department official, went to the CNMI with Sens. Daniel Akaka (D-Hawaii) and Frank Murkowski (R-Alaska) in the mid-1990s, he says, they attended the usual meetings arranged by local government officials, before feigning jet lag and returning to their hotel. Then, in the evening, they left the hotel and got a different tour from Labor Department investigators and Christian human rights activists. “They were quickly persuaded,” Stayman says. “Like I said, it was all Potemkin village.” Murkowski later told PBS that calling the conditions “unacceptable” was “putting it mildly.”

But Abramoff’s close relationship with House Majority Whip Tom DeLay, who visited the CNMI for New Year’s in 1997, ensured that Murkowski and Akaka’s attempts to revoke the CNMI’s immigration and minimum-wage exemptions met a certain death in the House. DeLay called the islands “a perfect petri dish of capitalism,” adding, “It’s like my Galapagos Island.” (Abramoff could not be reached for comment.)

As Abramoff’s clout expanded, Preston Gates’ payments from the islands rose from $100,000 in 1995 to more than $3 million in 1997. (In 2001, The New Republic reported that Pizzella made $175,000 per year.) Then Tenorio’s uncle ousted him from the governorship as the islands’ tourism industry tanked during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The next year, Preston Gates’ CNMI income dropped by more than half. To cover the shortfall, Abramoff turned to Willie Tan, the garment magnate. In a 1998 memo to a Tan Holdings official, Abramoff laid out a six-part strategy for representing Tan and the government. Pizzella was tasked with running the trips program—the importance of which “cannot be overstated,” Abramoff wrote.

Jack Abramoff leaves a federal courthouse after entering a plea agreement on three felony charges.

CQ Roll Call/AP

In 2001, Abramoff moved on to the lobbying firm Greenberg Traurig, where he continued to work on behalf of the CNMI. Instead of following him, Pizzella joined the George W. Bush administration as the chief of staff in the Office of Personnel Management. But Pizzella had made his mark as a lobbyist for the CNMI. By 2001, more than 100 thought leaders and lawmakers had made the journey to the CNMI, according to reporting by the Wall Street Journal and other outlets. “If you were a conservative intellectual and you didn’t get invited, you just knew you weren’t cool,” a source told The New Republic’s Franklin Foer in 2001. In 2007 and 2008, after Abramoff and Pizzella had stopped lobbying for the CNMI government, Congress overwhelmingly passed bills revoking the islands’ wage and immigration exemptions. Following a World Trade Organization agreement eliminating tariffs on US apparel imports from abroad in 2005, the CNMI’s garment industry all but disappeared.

Hardly anyone seemed to notice when Pizzella was unanimously confirmed by the Senate to be an assistant labor secretary a few months into the Bush administration. “Wait, exactly who is this guy again?” the textile union’s legislative director asked Foer at the time. Six months removed from lobbying, Pizzella was already calling his CNMI work “ancient history.” “I don’t want to go down memory lane,” he said in the June 2001 story. (President Barack Obama’s nomination of Pizzella to the Federal Labor Relations Authority in 2013 was similarly uncontroversial.)

At Greenberg Traurig, Abramoff took his influencing to new, and frequently illegal, levels. In 2008, he received a four-year prison sentence for charges including corrupting public officials, tax evasion, and conspiracy. The fraud Abramoff perpetrated against Native American clients got most of the attention, but in Abramoff’s plea deal, a January 2000 trip to the CNMI was included as one of many examples of how Abramoff provided golf and other “things of value” in exchange for “official acts and influence.” Twenty-one people were ultimately found guilty in the Abramoff scandal. Pizzella was not charged.

At Pizzella’s July confirmation hearing, Franken mentioned the people convicted in the Abramoff scandal. Pizzella was careful to point out, “I was not one of them.” Franken didn’t seem particularly impressed. “I understand that,” he deadpanned. “Congratulations.”

Image credit: Pizzella: Ron Sachs/ZUMA; Abramoff: Pablo Alcala/ZUMA