A coronavirus patient in Tehran, Iran.Rouzbeh Fouladi/ZUMA

The bigger the scientific study, the stronger the findings. That’s why nations are teaming up to launch a worldwide research project called SOLIDARITY to find a treatment for the deadly coronavirus. The study, announced by the World Health Organization last week, will include thousands of patients in several countries in an effort to determine if any existing drugs can safely treat the coronavirus.

“We commend the researchers around the world who have come together to systematically evaluate experimental therapeutics,” WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said while announcing the trial. “Multiple small trials with different methodologies may not give us the clear, strong evidence we need about which treatments help to save lives.” He added that “this large international study is designed to generate the robust data we need.”

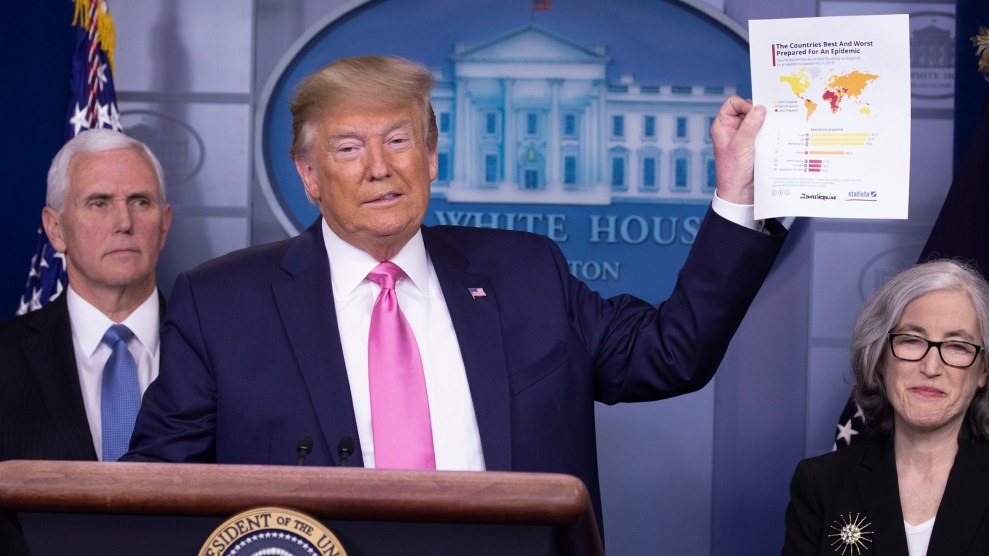

With a vaccine expected to be a year or more away, scientists and doctors are looking for existing treatments that can target the virus. While developing new drugs can take years—and testing their general safety years more—the medical community hopes that medications already on the market or in research can help, including drugs designed to treat HIV and ebola. The WHO panel that crafted the trial is focusing on four treatments that its experts believe are the most promising, according to Science. These include the malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, drugs that President Donald Trump has been hyping despite Science calling the data supporting their use both “murky” and “thin”; WHO initially decided there was “insufficient evidence” to investigate chloroquine, but agreed to include it after noting a need for a decision on its use after it received “significant attention” in several countries.

The trial makes it easy for patients anywhere to quickly become a part of the research. With a subject’s consent, physicians simply enter the data from a confirmed COVID-19 case into a WHO website, taking note of any underlying conditions such as HIV or diabetes. The physician next inputs which drugs are available in their area, and the website will assign the patient one of the experimental treatments. As Ana Maria Henao Restrepo, a medical officer at WHO’s Department of Immunization Vaccines and Biologicals, explained to Science, all that’s then left is for the physician to record when the patient left the hospital or died, how long the patient was in the hospital, and whether they required oxygen or a ventilator. “It will be important to get answers quickly, to try to find out what works and what doesn’t work,” she said. “We think that randomized evidence is the best way to do that.”

Thus far ten countries around the world have joined the trial, and researchers in Europe have announced a complementary study called Discovery that will exclude chloroquine. The United States was not among the countries that first pledged to participate.