Public health officials test for COVID-19 in Livingston, Montana, in December 2020.William Campbell/ Getty

This story was originally published by Undark and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

One afternoon this past December, a package arrived at Mora Valley Community Health Services in northern New Mexico. The rural clinic, which serves a county of 4,521 people, is nestled beside a pasture with a flock of chickens and a few goats. A mile up the road sits the town of Mora — a regional hub just big enough for a trio of restaurants, two gas stations, and a single-building satellite office for a nearby community college.

Shortly after the package arrived, clinic staff received an email explaining that this “ancillary convenience kit” was a test of the system designed to transport SARS-CoV-2 vaccines from the state’s warehouse to Mora and other rural communities across the state. While this package contained supplies for administering the vaccine — syringes, needles, alcohol swabs, and more — the real challenge would occur the following week. That’s when 100 doses were scheduled to be delivered, and the clinic’s staff would have 30 days at most to administer the doses before they spoiled.

As promised, the vaccine arrived on Dec. 21. Staff worked in phases, stationing patients in exam rooms in numbers to match the doses coming from each vial. Each patient completed a health questionnaire, received a shot, and then was monitored for 15 minutes to be sure the vaccine did not trigger an adverse reaction. Within a few weeks, all 100 shots were in arms.

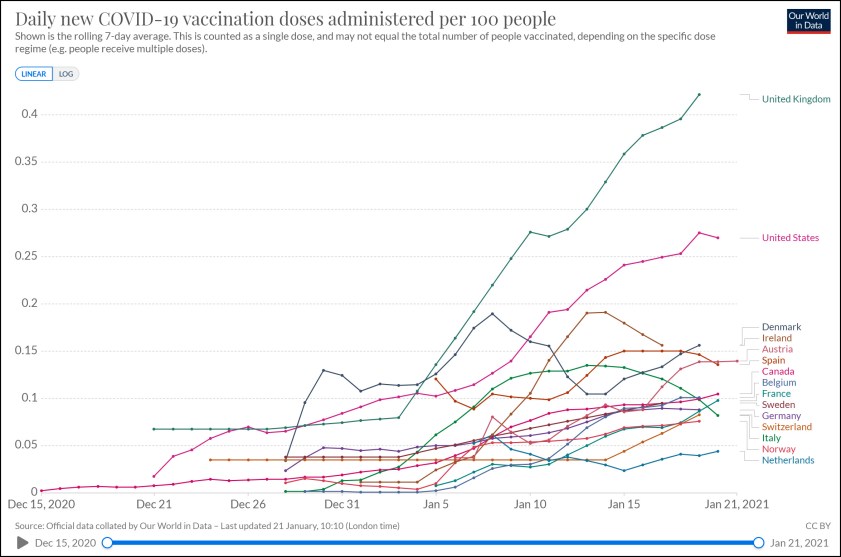

As the United States begins its massive vaccine rollout, health departments across the country are scrambling to plan and adjust, often while simultaneously managing a surge in new Covid-19 cases. “Just trying to keep up and stay alert of what new things are coming down the line is pretty critical,” said Jessica Martinez, a Mora Valley nurse. Rural clinics face unique challenges in getting highly perishable vaccines to residents who often live many miles away. “We’re kind of out here on our own,” she said.

Additionally, data show that rural residents are less likely to receive a flu shot than residents of metropolitan areas. This trend, combined with the reluctance of rural communities to embrace coronavirus mitigation measures, has some experts worried: “Think about a person who needs to drive one hour for a shot, then do the same 20 days later for a second shot,” said Diego Cuadros, a professor of health geography and disease modeling at the University of Cincinnati. “If it’s a person who maybe doesn’t think this is too important, or has some misperception or misinformation about vaccines, this is going to be extremely challenging.”

Ultimately, Cuadros and others worry that the virus might linger in pockets of rural America, from which it could reemerge into the broader population, compromising efforts to get the virus under control. To prevent this, health care workers are starting with a public information campaign, while state health departments are encouraging pharmacies to run outreach clinics and set up new sites for vaccinations. Currently, the most pressing issue facing less populated areas is how to store and administer vaccines before they lose their effectiveness.

The messenger RNA technology used to develop the two vaccines that have received approval in the U.S. so far — one developed by the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer and German drugmaker BioNTech and one by the biotechnology startup Moderna — requires that they both be kept cold. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine needs to be kept at a temperature between –112 and –76 degrees Fahrenheit, while Moderna’s lasts longest if kept between -13 F and 5 F.

Because of its large and far-flung rural population, New Mexico was selected by Pfizer as one of four states of varying demographics and geographies to participate in a pilot program for refining the deployment of its vaccine, both in the U.S. and around the world. The company designed a temperature-controlled shipment container the size of a carry-on suitcase that weighs about 70 pounds when filled with dry ice and up to 975 vials of the vaccine and can keep the vaccine viable for up to 10 days, or up to 30 days if the dry ice is refilled. As the first round of 17,550 doses of Pfizer vaccine was being moved around New Mexico in mid-December, 75 had to be discarded after a gauge indicated they’d become too warm, either a failure in the cold-storage system or in the data-logging device. After the losses, a state official said the devices’ temperature settings were recalibrated and an alarm set to go off if they began to warm.

Purchasing super-cold storage equipment is costly and demands a higher-voltage outlet, said Eric Tichy, vice chair of supply chain management for the Mayo Clinic. Stock of that equipment—particularly of the size that would be appropriate for smaller pharmacies and clinics—is also simply sold out. That may leave many of them leaning on Pfizer’s container and dry ice refills.

With 237 vaccines in development on the World Health Organization’s list of candidates, the future will likely include vaccines that tolerate warmer temperatures. Johnson & Johnson is expected to release information later this month on a candidate that needs only refrigerator storage and a single dose. “A lot of people are focused on that one,” Tichy said. “Especially for worldwide distribution, that’s a big deal.”

It’s also possible ongoing testing will show the two vaccines already in circulation remain stable at less cold temperatures, Tichy said. Initially, Moderna’s vaccine seemed to require super-cold storage, but it’s been shown to remain effective for up to 30 days in a refrigerator at up to 46 F.

The bigger challenge Tichy sees is that once a vaccine vial is opened, staff have just six hours to use all five or 10 doses it contains. “It’s a precious resource,” he said, “You don’t want to just give it to two people and have to throw out the rest of the contents. You want to get five people vaccinated.”

The first wave of inoculations targets health care workers and residents in long-term care facilities, so there’s a central location at which vaccines can reach them. For vaccinating the public at large, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has partnered with large national pharmacy chains, as well as networks of small regional chains and independent pharmacies. The incoming Biden administration has signaled it will continue with this strategy, noting in the outline of its vaccination plan that nearly 90 percent of Americans live within five miles of a pharmacy, while also acknowledging that more will be needed to reach those who live in more isolated areas.

The Rural Policy Research Institute at the University of Iowa found 750 counties nationwide with no partnership pharmacies, and another 334 with just one such pharmacy. The majority of states have at least one county without a partnership pharmacy, and large swaths of Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Texas, and smaller chunks of Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah, reported no partnered pharmacies.

“We need to be alert to the fact that it’s not as simple as thinking you’ve got a contract with 19 franchises and that’s going to cover the nation because Walgreens and CVS are everywhere — well, no they’re not,” said Keith Mueller, director of the Rural Policy Research Institute. “It doesn’t mean you can’t figure out a way. It just means you have to get to the next level of planning.”

In some states, that hasn’t presented much of a hurdle. Independent pharmacies have procured doses of the vaccines and done well administering them, but rates vary widely from state to state.

Rural communities often run short on resources, whether it’s cold storage facilities or a population of retired nurses and doctors to tap to help administer vaccines, he added. The geography can also compound the disparities in access that affect racial minorities.

Kim Atwater, who owns two pharmacies in rural New Mexico towns, decided that for now, it doesn’t make sense to order doses of the vaccines. “We don’t have refrigeration facilities to keep it,” she said. “We’re just a very, very small community.”

In rural areas, the lack of pharmacies and major medical centers means that much of the vaccination effort is falling to local health clinics like the one in Mora. “We know it’s a cardinal sin to waste a dose, and we are not trying to be wasteful,” Martinez said.

Unwillingness to get vaccinated may also present a hurdle. While some national surveys report growing numbers saying they will take a Covid-19 vaccine when it becomes available to them, Cuadros said he hasn’t seen that data broken down between rural and urban respondents. Data that tracked vaccination rates for influenza shows them much lower in rural areas.

Atwater’s conversations with locals suggest that pattern may carry over to the new vaccines. “There’s a lot of people who are just saying, ‘Oh, I’m not getting that,’” she said. “We hear a lot of, ‘That? No, no, not until there’s more testing done on it.’”

Mora bucked trends this fall by making flu vaccination more convenient, Martinez said. Her clinic offered drive-through clinics, welcomed walk-ins, sent staff to patients’ homes, and even invited a UPS driver to receive a shot after dropping off packages at the clinic. As a result, they administered 400 flu vaccines compared to roughly 250 last year.

But when it comes to the new Moderna vaccine they were set to receive, Martinez said, she still heard reluctance. A poll showed only 29 of about 86 clinic staff were immediately interested in taking the vaccine. In addition to providing those staff more information to ease any concerns, she reached out to the local ambulance service, the school nurse’s office, and even a long-term residential facility to add names to the list, rather than see doses go to waste. After ramped-up education efforts and a new mandate for employees, 80 staff members were vaccinated, according to Martinez.

The plan New Mexico submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention forecasts this need for flexibility, pointing out that if more doses arrive in a community than there are health care workers interested in taking it, the rules around who is first in line may need to relax.

The clinic has already worked to make it easier for residents to get a SARS-CoV-2 test. On a recent weekday afternoon, staff put out flags where the dead-end gravel road named for the clinic meets the highway that announced “Covid testing” and “flu shots.” By the time blue-gowned, masked, and face-shielded staff stepped outside, a line of vehicles threaded through the parking lot. Staff reached in the window of the first pickup truck in line, took a swab, and the driver pulled away and back onto the highway. Staff have bundled up to administer these tests even on days with below-freezing temperatures and frigid winds, and when snow has shut down other testing sites.

But with the CDC recommendation to watch people for 15 minutes after they receive a vaccine for adverse responses to it, Martinez said, a drive-through approach would be risky. Staff would have to try to keep an eye on patients through windshields, then rush into the gravel parking lot with a crash cart and epinephrine if someone had an allergic reaction. They’d considered erecting an insulated tent, but given the prioritization of elderly, potentially frail or vulnerable patients who wouldn’t do well in the winter weather, the private medical information elicited by the questions preceding a vaccine, and the need to have emergency equipment on hand, they decided to book people for 20-minute appointments inside the clinic. Now, they’re on standby for the second doses, getting “slammed with calls” from people wanting to get in line, and helping people who rushed to pop-up clinics in one town sort out how to get their second dose on time.

“It’s just going to take a lot of planning, and of course, trial and error,” Martinez said. “It is a little bit draining sometimes to try and make everything — the community — a better place and healthy and be committed to the organization and to our patients first and foremost, so we just try and tell people, ‘Wear your mask, wash your hands.’”