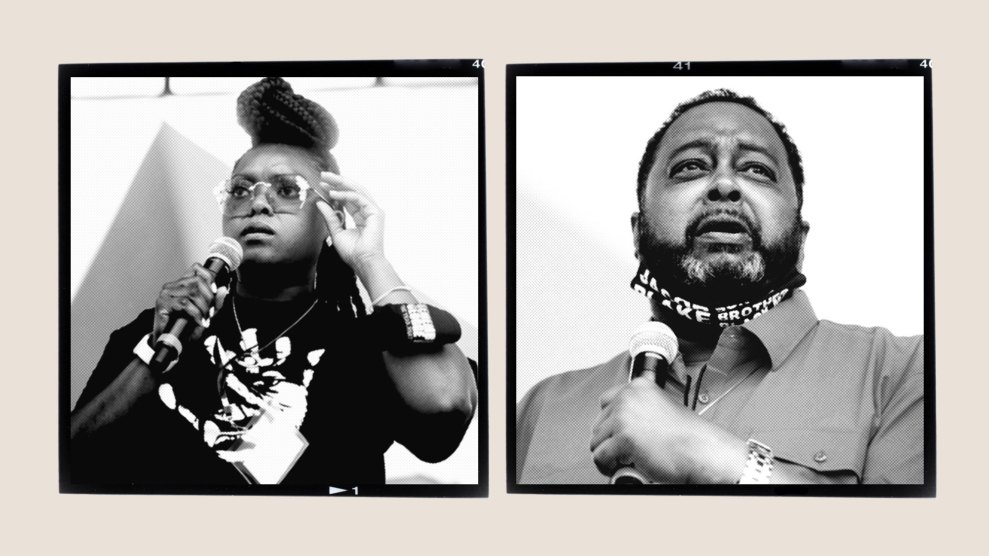

An image of Breonna Taylor during an event in Louisville, Kentucky, one year after her death. DeeCee Carter/MediaPunch /IPX/AP

More than two years after police barged into Breonna Taylor’s Kentucky home in the middle of the night and shot her dead, a former cop involved with the case has finally been convicted.

Kelly Goodlett, an ex-detective for the Louisville Metro Police Department, was not present during the March 2020 raid. But she admitted on Tuesday in federal court that she helped a colleague lie to convince a judge to sign off on the no-knock warrant that allowed officers to enter the home in search of drugs. To get the warrant, detectives allegedly claimed to have evidence that they did not have. Taylor, who had been in bed when officers entered, was a 26-year-old EMT. No drugs were found on the premises.

The conviction is the first in a case that spurred massive nationwide protests and inspired lawmakers in multiple states to ban or restrict no-knock raids. Federal prosecutors have also charged two other Louisville officers for their role in acquiring the search warrant, and a fourth officer for violating Taylor’s civil rights and the civil rights of her neighbors by blindly firing 10 bullets through two apartments during the raid. The two cops who actually shot Taylor have not been charged. Federal prosecutors said those officers, Jonathan Mattingly and Myles Cosgrove, did not know their colleagues had lied to obtain the warrant. State prosecutors also previously declined to press charges against them.

Taylor is not the first person to die after police misled judges to obtain search warrants. In fact, cops commonly lie to justify their raids, according to scholars who study the issue. The New York Times recently highlighted other cases in Houston, Baltimore, and Atlanta. “The disturbing ease with which one can find examples of falsified warrant applications,” Stephen Gard, a professor emeritus at the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, wrote in a legal journal back in 2008, “provides powerful evidence of the serious problem of police perjury in our society.”

And as cops use false information to obtain warrants, the number of raids they pursue has skyrocketed around the country. As I previously reported, officers in the United States conduct an estimated 60,000 no-knock and quick-knock raids each year, compared with around 3,000 back in 1981. Black and Latino people are disproportionately targeted. And no-knock raids like the one in Louisville are especially dangerous, because of the confusion they cause: When the cops barged into Taylor’s home, her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, mistook them for intruders and fired a weapon toward them. The cops returned fire, striking Taylor multiple times.

In Taylor’s case, federal prosecutors allege that the cops lied repeatedly to justify their raid. Goodlett, the ex-detective who was convicted this week, said she did not stop her colleague Joshua Jaynes when he falsely claimed on a warrant application to have proof from a postal inspector that a drug dealer was sending packages to Taylor’s apartment. (Jaynes has pleaded not guilty.) According to prosecutors, the warrant application also stated that the drug dealer, Taylor’s ex-boyfriend Jamarcus Glover, used her address as his own, even though the detectives knew he did not live there.

The lies continued after the raid. As public backlash grew over Taylor’s death, according to prosecutors, Goodlett and Jaynes met in Jaynes’ garage to scheme how they could cover up the false statements they had made. “During the garage meeting,” according to a Justice Department statement, “the other detective told Goodlett that they needed to get on the same page because if he went down for the false warrant, she would go down too.”

Goodlett faces up to five years in prison and a $250,000 fine.