In 1905, the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station published a supplement to their annual report: two big, hulking, beautifully illustrated tomes called The Apples of New York, Volumes I and II. The nearly 800 pages summed up over two decades of horticultural research, but what the author really wanted to brag about was the pictures—all made under the “personal supervision” of the Station’s head horticulturalist himself.

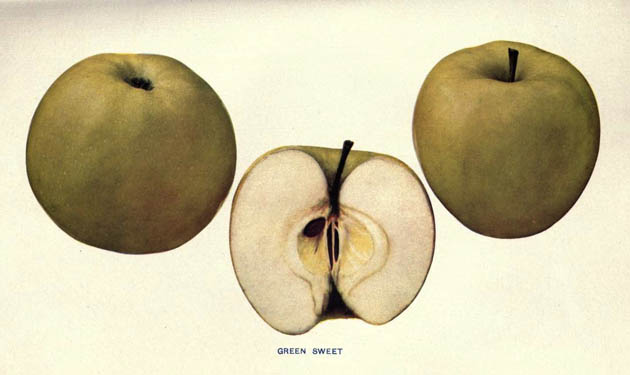

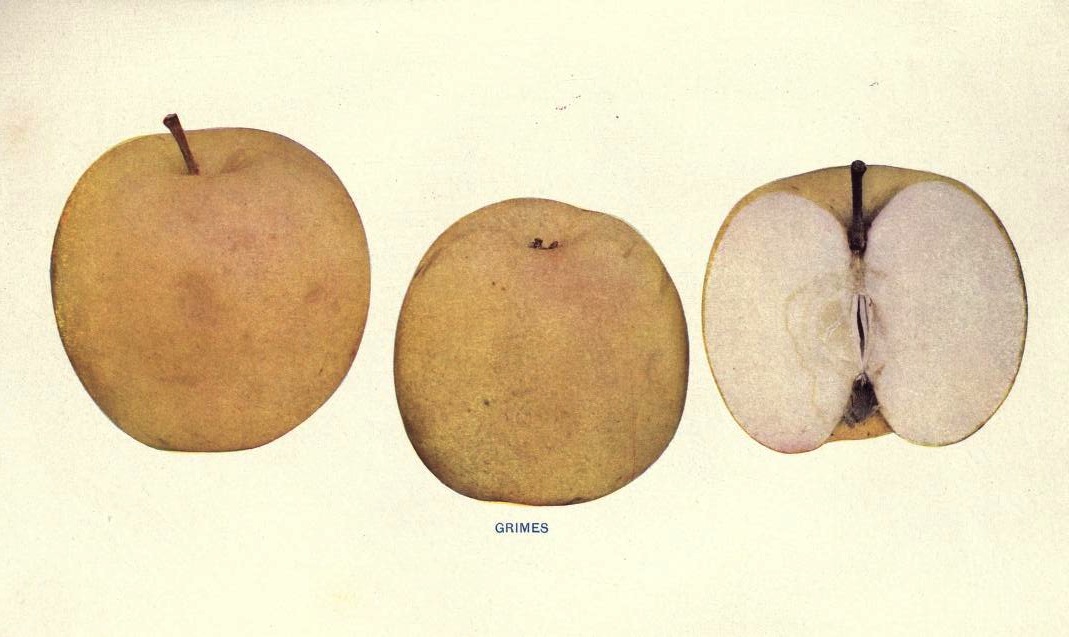

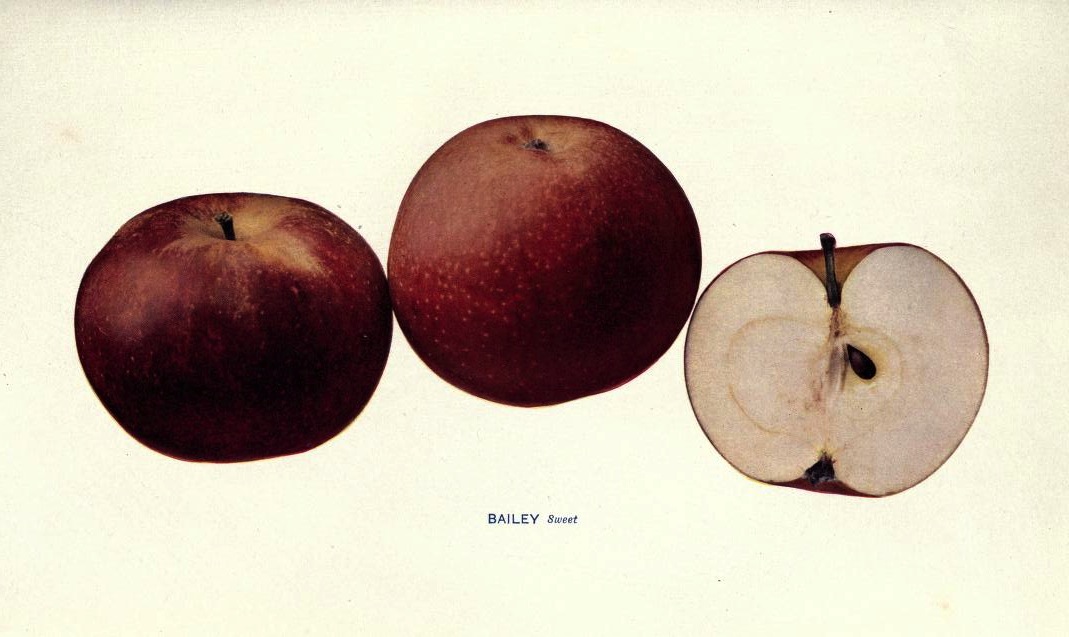

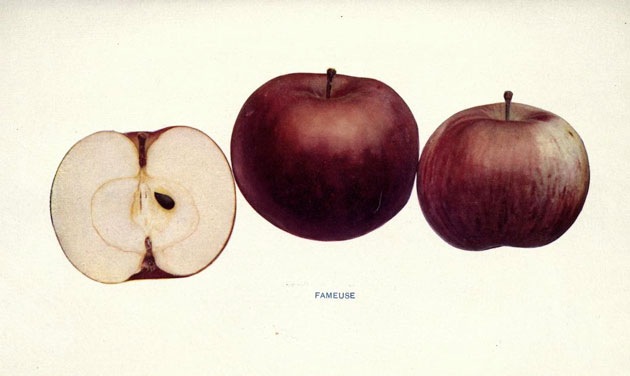

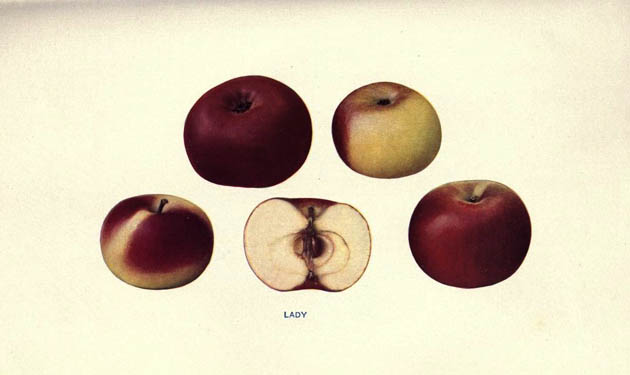

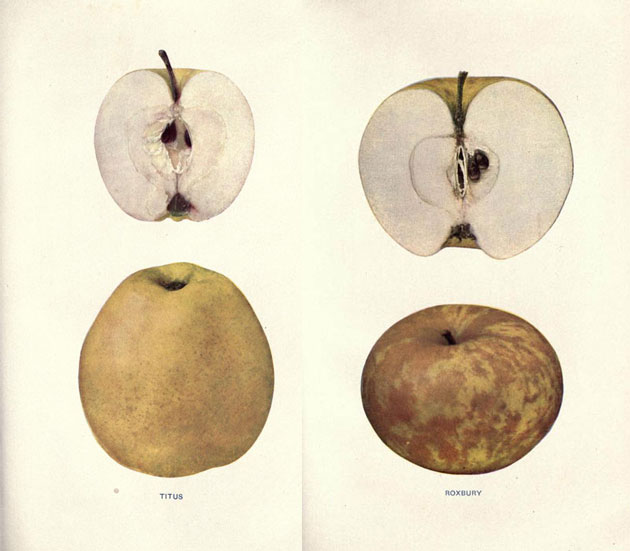

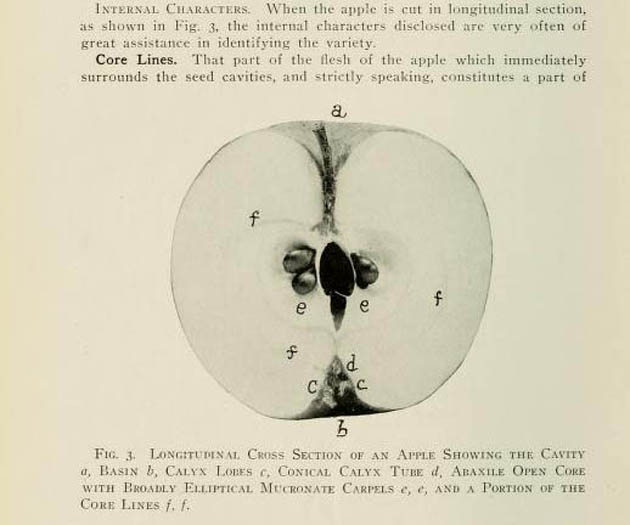

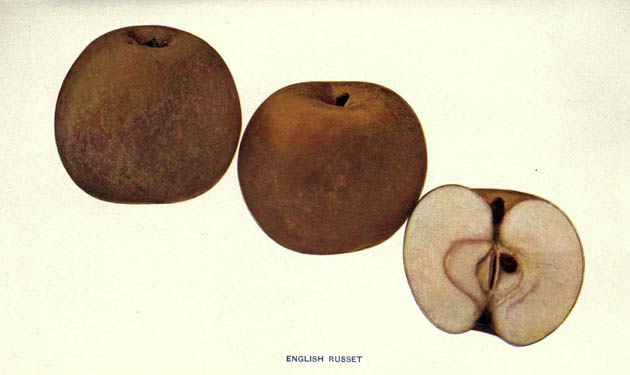

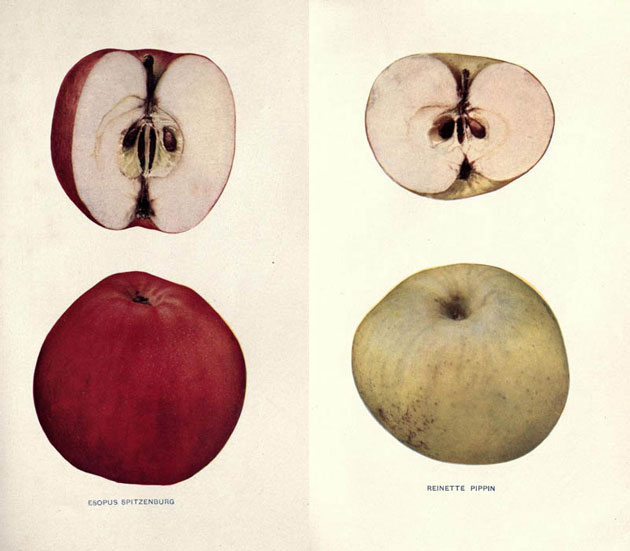

Its nearly 200 illustrations really are worth bragging about, and not just for their scientific value either. They capture the full beauty of apple hues during a time before widespread color photography. On top of detailed historical and scientific scholarship of 800 apple varieties, the books also teaches readers step-by-step how to identify a mystery apple.

Today, the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station has the world’s largest collection of apple varieties—a pomological Noah’s Ark. Its 2500 apple varieties hail from as far away as Kazakhstan, where apples first originated. And the Station’s been noticed before: Michael Pollan profiled the place in his book The Botany of Desire, and Venue recently did a great interview with Jessica Rath, a ceramic artist inspired by the Station’s apple collection.

I first discovered The Apples of New York while fact checking Rowan Jacobsen’s feature about heritage apples—the thousands of apple varieties that used to thrive in the US but largely disappeared with industrial agriculture. In 2013, I fully expected the best apple resource out there to be a shiny mobile app that could identify fruit with a snap of a photo. But no. John Bunker, the Maine apple detective profiled in Jacobsen’s piece, instead directed me to a book published over 100 years ago.

Despite its old age, The Apples of New York remains one of the finest resources for the amateur New England apple enthusiast, in part because it is freely available online. The most easily accessible copy is digitized courtesy of the Internet Archive’s Open Library project. The original physical copy is housed at the Prelinger Library, a privately funded public library tucked away in a San Francisco warehouse. I paid them a visit this week to see the illustrations in person—they look even better not washed out by a scanner’s flash—and figure out how a New York state’s annual report made it to California.

Rick and Megan Prelinger told me that the agricultural reports were printed and often sent to a local politicians, who then gave them away as gifts. One edition I found online carries the stamp of the Hon. Josiah Newcomb, a New York state congressman from the early 20th century. From there, the books’ provenance became murkier. The Prelinger’s edition used to belong to a different (unknown) library, and they said they likely acquired it through a government documents exchange.

But we don’t necessarily need yellowed old books to get a taste of pomological history; even a trip to the ordinary supermarket is a direct line to the apples of yore. A McIntosh apple illustrated and described a century ago in The Apples of New York is exactly the same as one I can buy today in a California supermarket.

That’s because apples of the same variety are all clones. Mix the genes of any two apple trees, and you’re unlikely to get the exact combination necessary for the familiar tart red-and-greenness of a McIntosh. Instead, orchardists cut a twig from an existing tree and graft it onto rootstock, growing a genetically identical apple tree. Occasionally, the offspring of two different trees does produce an apple worth keeping. And that’s when you get a name and photographs and maybe even supermarket fame.