A security light in a Tres Piedras, New Mexico, parking lot. "If you look closely, there's a shielded light in the background lighting the post office parking lot," Paul Bogard says. "The bright light is totally unnecessary."Paul Bogard

A country whose capital, Paris, made history with its “City of Light” glowing streets is suddenly trying to dial them down. Starting this summer, a French decree mandates that public buildings and shops must keep lights off between 1 a.m. and 7 a.m in attempt to preserve energy and cut costs, and “reduce the print of artificial lighting on the nocturnal environment.”

As France’s move suggests, civilization’s ever-growing imprint on the night sky has more than just stargazers concerned. In his new book, The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light, writer Paul Bogard bemoans how our last dark spaces are slowly being devoured by the “light trespass” of artificial rays. A team of astronomers recently projected that while the US population is growing at a rate of less than 1.5 percent a year, the amount of artificial light is increasing at an annual rate of 6 percent. It’s more than just a nostalgia for primordial darkness that’s eating at Bogard: Too much light causes animals to go haywire, derails natural cycles, and damages human health.

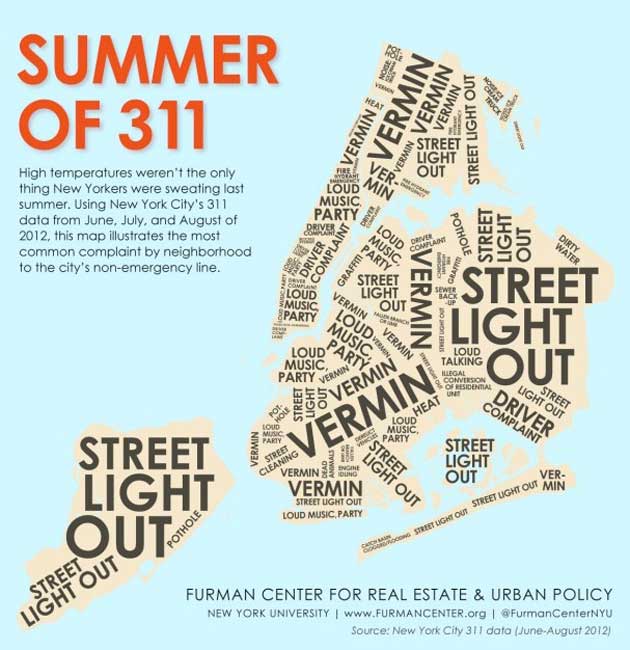

The greatest sources of light pollution in cities worldwide are street lamps and parking lots, partially because we’ve been bred to believe that public lighting equals safety. Take this recent map of the number one 311 complaint of New Yorkers during the summer of 2012; people wig out when there’s a dark bulb on their block.

But there’s a chance we have it all wrong, argues Bogard. In the late ’70s, a US Department of Justice report found no statistical evidence that street lighting reduced crime. More recently, similar findings—such as this 2008 review by California’s public utilities company—have been largely ignored by the general public.

Optometrist Alan Lewis, former president of the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, argues in the The End of Night that the glare of poorly designed street lamps (“probably eighty percent of street lighting”) can even make it harder to see things at night. Our eyes don’t have a chance to adjust to darker areas, and the extreme contrasts make our night vision poor.

It gets much worse than not being able to see in the dark. Scientists have unearthed troubling links between artificial light and our most feared diseases: obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular risk, and cancer. Apart from preventing people from getting adequate shut-eye, electric light at night has been shown to suppress the body’s production of melatonin, which is thought to play an important role in keeping certain cancers, such as breast and prostate cancer, from growing. Potent “blue” lights—such as those used in certain energy-efficient LEDs, and on tablets, cellphones, computers, and TVs—may be the worst culprits. “It turns out that the wavelength of light that most directly affects our production of melatonin at night,” writes Bogard, “is exactly the wavelength of light that we are seeing more and more of in the modern world.”

If our hyper-luminous cities put human health at risk, they may have even bigger repercussions for the animal world. Thirty percent of vertebrates and more than 60 percent of invertebrates are nocturnal, and artificial illumination screws up their pollination, breeding, feeding, and migration patterns. In 2011, for example, upwards of 1,500 grebes migrating over Utah died after crashing into parking lots they mistook for ponds after being confused by city lights bouncing off of clouds.

Drawing on memoir, literature, science, and history, The End of Night makes a compelling (if sometimes long-winded) case for turning down the national dimmer switch. As it turns out, people have been experimenting with ways to do that, from policies to products, for some time now. A roundup of a few bold ideas for cutting light pollution:

1. Make laws against excess light.

France isn’t the only place attempting to control light pollution. The Czech Republic made headlines in the early aughts for being the first to have a countrywide light pollution law, largely due to the efforts of the country’s astronomers. Because of their city’s proximity to the Lowell Observatory, astronomers in Flagstaff, Arizona, have been trying for decades to tamp down nocturnal glow, and their efforts paid off: In 2001, Flagstaff was declared the first International Dark Sky City.

In the ’90s, New Mexico’s Heritage Preservation Alliance starting arguing that the dark night sky was part of the state’s cultural heritage, resulting in the Night Sky Protection Act in 1999, which regulates outdoor night lighting. In 2009, Gov. Bill Richardson added a $25 fine for violations and an enforcement clause to bolster the law’s effect.

According to a roundup by the British parliament, at least 10 US states and several other countries have proposed related legislation. So far, the biggest obstacle to such laws still tends to be enforcement. “You can have a statewide ordinance, but there are no light pollution police,” Bogard tells me over the phone.

2. Install fixtures that don’t shine into the sky.

On his visit to the region of Lombardy in Northern Italy, Bogard walked past unusual streetlights:

Although they were in the shape of a regular carriage light, with four rectangular sides, there was no glass—and, um, no lamps. Actually, there were…but the lamps were housed up inside the top of the fixture.

The lights he describes are referred to as “full cut-off” fixtures, designed to prevent light from escaping horizontally and upwards. According to an Italian dark sky organization, more than 30 percent of public illumination is dispersed towards the sky. Full cut-off lights are said to minimize this scattered light while still emitting just as bright of a glow—and saving energy. When Calgary, Canada, experimented with retrofitting its city lights with full cut-offs starting in 2003, it estimated energy savings of C$1.7 million a year.

3. Make lights that can talk to the moon.

San Francisco-based design collective Civil Twilight turned heads in 2007 with a proposal for “lunar-resonant street lamps,” which would use bulbs that respond to ambient moonlight. The LED bulbs combined with a sensitive photo-sensor cell would dim and brighten each month depending on the lunar phases as well as cloud cover and other environmental factors. One of the project’s designers said in an interview that she hoped the lights could “alter our perception of cities at night” as well as encourage “moon-based activities.”

4. Engineer glowing plants.

A group of biotechnologists have begun to experiment with synthetic biology to make plants glow, “potentially leading the way,” as the New York Times puts it, “for trees that can replace electric streetlamps and potted flowers luminous enough to read by.” Aiming to fund $65,000 through its Kickstarter campaign, Glowing Plants ended up with almost half a million in its coffers after thousands of backers eagerly dished out for the experiment earlier this year.

MoJo food and ag blogger Tom Philpott isn’t so sure. “Big agrichemical, pharmaceutical, and life-sciences firms will quietly take over, eventually dominating the research and deployment” of “wondrous toys” like Glowing Plant, he predicts in a recent post.

5. Drive electric cars.

Say there’s finally a mass movement towards electric cars: “Once we’re paying to charge our cars at night,” Bogard says, “there’s no way we’re going to be able to keep buying as much electricity.” Outdoor lighting—such as that used for marketing purposes at gas stations and malls—might become more of a treasured commodity. The good thing about the energy crisis, a British astronomer told Bogard, is that it may get people to notice all the energy wasted on lighting.