Tu ren/ZUMA

This story first appeared on the Guardian website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The Virgin entrepreneur, Sir Richard Branson, has been a leader on the environment, putting up a $25 million prize to encourage new technologies that scrub carbon dioxide from the air, and supporting sustainable safari resorts in Africa.

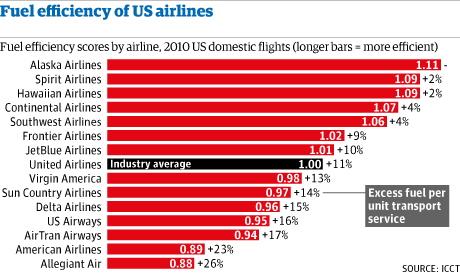

But the US branch of Sir Richard’s aviation empire, Virgin America, fell below the industry average on fuel performance standards, a new study of the US domestic air industry said on Tuesday.

Virgin America scored below the industry average for fuel efficiency among 15 airlines operating on domestic US routes in 2010, the report by the International Council for Clean Transport found.

The top spot for fuel efficiency went to Alaska Airlines, and the worst performer, Allegiant Airlines, came in at 26 percent, the report found.

But the sub-par performance for Virgin America—which means that its fleet on average produced more greenhouse gas emissions per passenger than other domestic US carriers—took even the research team by surprise.

Aviation is the fastest growing source of the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change, and the United Nations is scheduled to meet later this month to try to reach a carbon-cutting deal for global aviation industry.

Sir Richard has been a champion of low-carbon fuel alternatives for the aviation sector as well as for shipping, and Virgin five years ago flew a plane to the Netherlands on coconut fuel.

“Virgin America is only partially explainable to us,” said Dan Rutherford, aviation and marine director for ICCT and an author of the report.

Virgin America’s new fleet of A319 and A320 Airbuses were certified about 20 years ago. “This is a best guess. But just because an aircraft is new doesn’t necessarily mean it is technologically advanced,” he said.

Rutherford also noted that Virgin was using relatively small planes for its long cross-country routes compared to other airlines, which hurt its fuel efficiency. It also offered more spacious seating, or fewer passengers per plane.

The company said it had built sustainable practices into its operations since launching Virgin America in 2007.

“Although our fleet is one of the most fuel efficient in the industry, we are continually looking for new ways to reduce our footprint through operational practices and technologies,” Virgin America spokesman Madhu Unnikrishnan said in an email.

He said the company’s newest planes were equipped with wing-tip devices, known as Sharklets, which make aircraft up to 8 percent more fuel efficient.

Virgin America did come out on top in fuel efficiency on one of its main US routes, from Los Angeles to New York City.

But it was firmly in the middle for fuel performance on other routes included in the study, and on the San Diego-San Francisco run, Virgin America came in last of the three airlines serving that sector for fuel performance, the study found.

The Virgin Group is a minority shareholder in Virgin America, under US regulations which limit foreign ownership of airlines to 25 percent.

The ICCT report, based on fuel consumption records provided by the airlines, found a wide spread in performance between the airlines—even in some instances on the same routes.

Alaska Airlines, the cleanest carrier, was 26 percent more fuel efficient than the dirtiest airline, the budget carrier Allegiant Air, the study found. Spirit Airlines, also a budget carrier, came in second, and Hawaiian Airlines third. The cleanest “legacy” carrier was Continental.

The performance gap was even more striking on some individual routes. In one case, the researchers uncovered an 87 percent difference in fuel efficiency between Southwest, the most efficient carrier, and Delta, the least, on the Chicago-New York route.

Most of the difference was due to the technology of the aircraft, with those equipped with wing-tip devices achieving greater fuel efficiency. “Technology is a big part of the puzzle,” Rutherford said.

For long-haul journeys, direct flights were greener than more circuitous routes.

On short hops, turbo-props were cleaner than the smaller regional jets with 50-110 seats, Rutherford said.

Also read: “Jet Blues,” in which the daughter of a commercial pilot decides to forsake flying and stick within 100 miles of home.