This Kentucky coal-fired power plant will be updated to continue operation under the new rules. Dylan Lovan/AP

Update, Monday, June 2, 9:45 a.m. EDT: You can check out our live coverage of the announcement and reaction to the proposed power plant regulations here.

Update, Sunday, June 1, 6:30 p.m. EDT: The Wall Street Journal is reporting that on Monday the EPA will announce sweeping new limits on carbon dioxide pollution from the nation’s existing power plants. The plan is said to require a nationwide reduction in carbon emissions by an average of 30 percent over 2005 levels by 2030, with different specific targets for each state. The rules, which will have a one-year public review period before becoming final, could represent one of the biggest actions taken by the US government to slow climate change.

On Monday, President Obama is set to unveil details of the cornerstone of his climate plan: Limits on carbon dioxide emissions from the nation’s fleet of existing power plants. The rules are likely to be the biggest step toward the president’s goal of cutting US greenhouse gas emissions 17 percent by 2020. The rules are already taking heat from the fossil fuel industry and Republicans in Congress, despite having the support of a majority of Americans. So what’s all the hullabaloo about, exactly? Here’s what you need to know:

Why regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants? By now it’s well established that carbon dioxide from human activities is the single biggest driver of climate change. The news this month that severe glacial melting in Antarctica has already nearly guaranteed up to 10 feet of global sea level rise was just the latest reminder of the dire need to slash our carbon pollution. Power plants and vehicles are the two biggest sources of this pollution in the United States, accounting for about 38 and 31 percent of carbon emissions, respectively. The Obama administration has already taken aim at motor vehicles; it placed new emissions limits on cars in 2009 and ordered them for heavy-duty trucks this year. But there are currently no restrictions—at all—on how much carbon pollution the nation’s existing fleet of power plants can produce.

In the United States, as in many countries, the single biggest source of electricity is also the dirtiest: Domestic coal-fired plants produced 1.45 billion metric tons of CO2 in 2012, according to Environmental Protection Agency data, equal to about 305 million cars. That’s more than 67 percent of the power sector’s total carbon emissions, even though coal accounts for just 37 percent of the energy mix. Put another way, coal-burning power plants in America alone exceed the total carbon emissions of Central and South America.

Limiting emissions could also have benefits beyond slowing climate change: A study released this week by public health researchers at Harvard and Syracuse universities found that controlling the amount of carbon released by power plants also cut down on emissions of toxic pollutants like sulfur dioxide and mercury, which contribute to asthma, heart disease, and other serious health impacts—not to mention that sulfur dioxide causes acid rain.

America’s carbon emissions have declined from their 2007 peak, and last fall the EPA issued rules for power plants that could prevent many (or any) new coal plants from being built. (For the time being, thanks to the fracking boom, cheap natural gas has made construction of new coal plants unlikely for economic reasons.) With next week’s rule, the EPA is looking to fill in the deepest part of America’s carbon footprint.

How big an effect will this have? It’s impossible to say exactly without seeing the specific proposed limits; the New York Times is reporting the rules could require cuts in CO2 emissions of up to 20 percent. The middle range of projections from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is a reduction of 544 million metric tons by 2020, equivalent to taking about 114 million cars off the road.

Does the EPA have legal authority to do this? Yes. Based on the 2007 Supreme Court case Massachusetts v. EPA, the EPA has had the authority to treat greenhouse gases as dangerous pollutants, enabling it to use the Clean Air Act to place limits on them. More specifically, the 2011 Supreme Court case American Electric Power v. Connecticut found that the EPA has the authority to regulate carbon pollution from power plants.

That doesn’t mean legal challenges aren’t lining up already, from coal industry groups, the US Chamber of Commerce, state Republican attorneys general, and others. “I’m ready to get it over with,” says Paul Bailey, vice president for federal affairs at the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE). “I want to see what this looks like, and whether it’s something we’ll have to push back hard on.”

The key legal question is whether the courts will validate the EPA’s approach of including “outside-the-fence” measures (see below) in its assessment of how much a state can be expected to cut emissions. Bailey says the Clean Air Act doesn’t provide for anything except regulations on the plants themselves, so the EPA can’t set a standard that requires states to do anything else. But environmentalists Doniger and Ceronsky argue that because the power system is, in fact, a system with many moving pieces, there’s no legal reason why regulators and utility companies should look just at power plants and ignore things like efficiency standards and the overall energy mix.

Doniger adds that companies already use a cap-and-trade system (one of the primary “outside-the-fence” approaches) to comply with Clean Air Act regulations on the sulfur dioxide emissions that cause acid rain: “We think this can be done in a very sound legal manner.”

“The fact that [power plants] are still the largest chunk, and there are no limits, is an unreasonable and irresponsible state of affairs,” said Megan Ceronsky, an attorney with the Environmental Defense Fund. “This moment in time when we can accelerate the transition away from higher-emitting sources of power is hugely important.”

So what is the EPA gonna do about it? We won’t know the details of the EPA plan until it is announced on Monday. Policy watchers in Washington expect it to draw heavily on a proposal from the NRDC, which recommends using the Clean Air Act to limit CO2 emissions in a somewhat different way than the law has been used in the past to limit other hazardous pollutants.

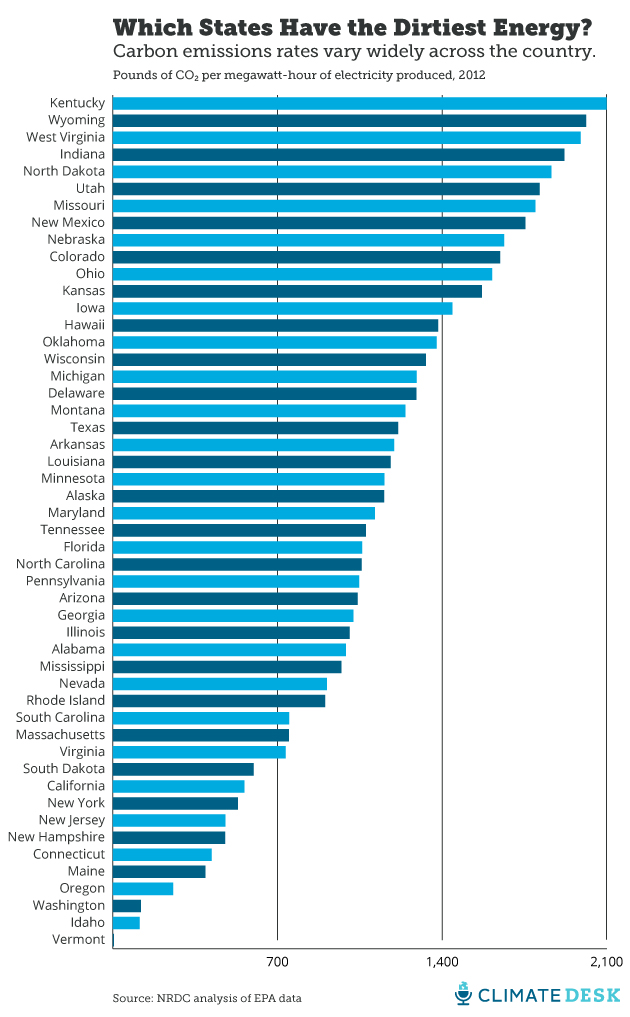

The previous strategy typically involved setting a standard for individual power plants. Under the NRDC plan, the EPA would conduct an analysis of the potential emissions reductions each state could achieve in a best-case scenario using existing technology at reasonable cost. In other words, each state will get a reduction target based on what it could reasonably be expected to achieve if it started taking carbon pollution very seriously on its own. For a state like California, which is way out front on clean energy, energy efficiency, and other emissions-reducing schemes, that goal might not be very different from what’s already in place. But coal-reliant states such as Kentucky, West Virginia, or Indiana, which have relatively high emissions relative to the energy they produce, will have much more aggressive goals—even though their emissions rates will still end up higher than other states.

The chart below shows which states will likely be most affected by the new policy:

Because the benchmark is different for each state, the EPA will allow each state to draft its own plan for how to achieve it. This could include so-called “inside-the-fence” measures, like installing carbon-scrubbing technology on existing plants and “outside-the-fence” measures like investing in renewable energy and energy efficiency, participating in a carbon pricing system, or shifting more of its electricity production to cleaner plants.

With many more options on the table than simply shuttering coal plants, the rules look less like an Obama “war on coal” and more like an opportunity for states to chart their own course in a less carbon-intensive economy. One Midwestern utility company has already proposed creating a regional price on carbon that would make electricity from coal more expensive than electricity from other sources, thereby decreasing demand for these plants. Even in coal states, achieving the goals might simply mean adopting basic clean-tech standards that are commonplace elsewhere. Indiana, for example, has “a lot of low-hanging fruit that California has already picked,” says David Doniger, director of NRDC’s Clean Air Program.

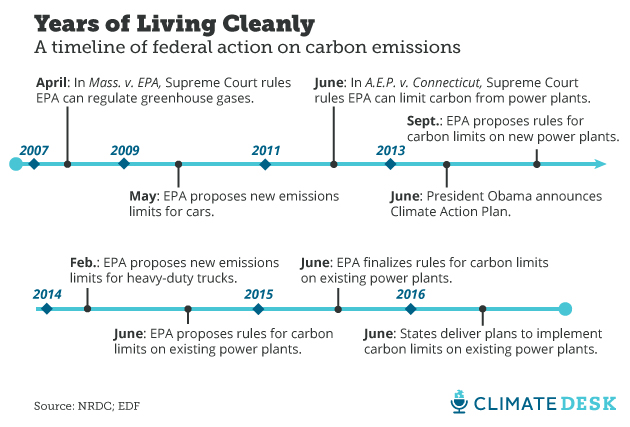

What’s the timeline? Glad you asked:

What else are critics saying? The US Chamber of Commerce released a report Wednesday predicting that the new rules could cost the economy $1 billion a year in lost jobs and economic activity. The National Mining Association is running radio spots claiming they will lead to an 80 percent jump in electricity bills. The pro-coal group ACCCE conducted its own study, and concluded that the rules could run up $151 billion in additional energy costs for consumers by 2033.

The trouble with such predictions, counters the Environmental Defense Fund’s Ceronsky, is that the economic impact of the rules will depend entirely on how states chooses to implement the standards. “They have the flexibility to make this as cost-effective as they can,” she says. British Columbia’s carbon-tax system, for example, has netted more than $5 billion in revenue since 2008, while carbon emissions plunged seven times more than they would have otherwise. And although the NRDC predicts that full implementation of the most rigorous version of the rules could cost up to $14.6 billion nationwide, it predicts savings of up to $53 billion in avoided health and climate impacts, and $121 billion in energy efficiency and renewable energy investments pumped into local economies.

The ACCCE’s Bailey admits that giving states flexibility to make their own plans was a more agreeable option than a top-down dictum, but adds that he’d rather carbon not be regulated at all. “I think the right way is to go back to Congress and see if we can work something out there,” he says. “But I don’t see anything happening on that anytime soon.”

Why should the United States bother to act if China, India, and other big polluters aren’t? For one thing, China isn’t sitting on its hands, either. Over the last several years, it has rolled out a series of municipal cap-and-trade schemes for carbon and power plant standards for other pollutants.

Still, Chinese energy policy analysts will be watching this rollout closely, says Ella Chou, a senior research assistant at the Brookings Institute’s China Center. One important question will be whether decreased demand for coal in the United States as a result of the new rules will lead to increased exports to China, potentially lowering coal prices there and increasing the country’s already severe dependence on it. In that case, America would simply be offshoring its emissions, which would make the rules good for domestic health, but a wash for climate change. “That would be good for Chinese industry, but bad for the Chinese environment,” Chou says.

Robert Stavins, an environmental economist at Harvard and an expert on international climate negotiations, says the new rules will probably not sway other industrialized nations to sign on to a new global climate treaty at the planned UN conference next year in Paris. But it could at least lessen the harsh criticisms of the United States from developing countries. At the very least, says the NRDC’s Doniger, the announcement will be a signal that Obama is serious about tackling climate change. “Every big country needs to know that every other big country is in the game,” he said. “This is the US’s way of showing that it’s in the game.”