<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-196462532/stock-photo-dead-honey-bee-isolated-on-the-white-background.html?src=j1_cBS5QY8prPdoDrq2azA-1-0">Protasov AN</a>/Shutterstock

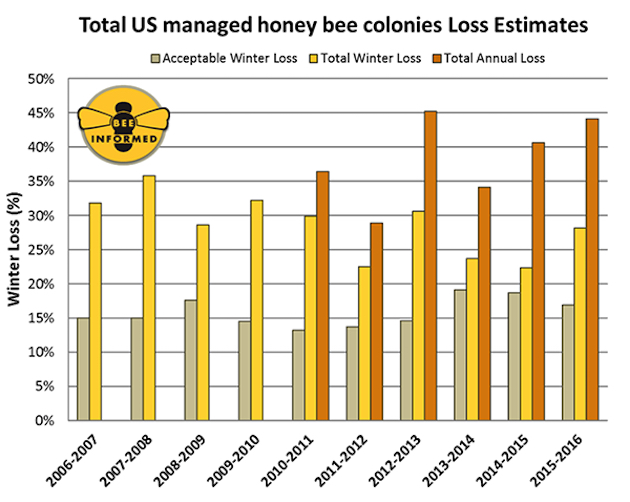

About a decade ago, beekeepers began noticing unusually steep annual hive die-offs. At first, they’d find that bees had simply abandoned hives during the winter months—a phenomenon deemed “colony collapse disorder.” In more recent years, winter losses have continued at high levels, and summer-season colony collapses have spiked. The Bee Informed Partnership, a US Department of Agriculture-funded collaboration of research labs and universities nationwide, tracks this annual beepocolypse, and the latest results, for the year spanning April 2015 to April 2016, are a real buzzkill:

“Acceptable winter loss” measures what beekeepers consider normal attrition. Last season, total losses were nearly triple the acceptable rate—forcing beekeepers to scramble to form new hives, an expensive and time-consuming process. They’re not the only ones with a big problem on their hands: About a third of the US diet comes from crops that rely on pollination, the great bulk of which comes from these beleaguered hives.

So far, researchers have not come up with one definitive reason for the dire state of bee health. Suspects swarm like characters in a drawing-room murder mystery. “A clear culprit is the varroa mite, a lethal parasite that can easily spread between colonies,” the report states. “Pesticides and malnutrition caused by changing land use patterns are also likely taking a toll, especially among commercial beekeepers.”

As I’ve written about in the past, neonicitinoid pesticides and a new class of fungicides likely share much of the blame for the vast honeybee die-offs; more here, here, and here. Unfortunately, these chemicals are still widely used on farm fields, and hotly promoted by agrichemical companies.