Coal miners wave signs at Trump's May 5 rally in Charleston, West Virginia.Steve Helber/AP

This story was originally published by New Republic and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

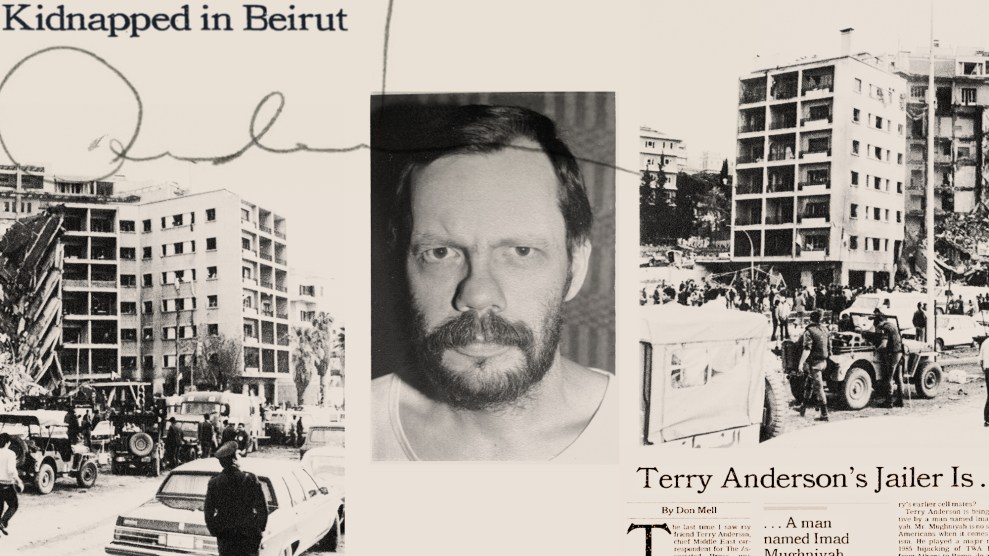

Of all the scenes of devastation in Puerto Rico caused by Hurricane Maria, one video has stood out. Shot from a balcony or rooftop, it depicts six seconds of horror: the city of Guayama, on the island’s southern coast, engulfed by a violent river. Deep, fast-moving water rushes through the streets, slipping over cars and picking up debris. The images would be jarring in any city, but they are particularly terrifying in this one. Guayama is home not just to 42,000 people, who are now struggling to survive, but also to a five-story-tall pile of toxic coal ash—another environmental catastrophe in the making.

Weeks after Hurricane Maria’s landfall, the status of Guayama’s coal-ash pile remains unclear. How much of this waste—the leftovers from burning coal—got into the floodwater or into the air? The company that owns the pile, AES Puerto Rico, did not respond to requests for comment. But scientific researchers have long raised concerns that the coal ash, which contains high levels of arsenic, mercury, and chromium, represents a massive health hazard—one that Maria has now likely exacerbated.

This is hardly an isolated issue. There are more than 1,000 coal-ash storage sites across the United States, from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Denver, Colorado. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the coal industry generates 130 million tons of ash each year, making it one of the largest sources of industrial waste in the country. According to the Sierra Club, this waste has contaminated more than 23,000 miles of waterways—including nearly 400 bodies of water used for human consumption. Duke University scientists have found that coal-ash storage ponds consistently contaminate nearby water sources, threatening both wildlife and people.

The consequences for human health can be serious. Families living near a coal-ash pond in Belmont, North Carolina, for example, have reported abnormally high rates of cancer, and in 2015, the state advised residents not to drink tap water or cook with it. The coal industry hotly disputes the idea that coal-ash ponds are responsible, but environmentalists argue that the link appears clear. “We’ve had really high spikes in arsenic in our main drinking water source in the region, and it’s because for years we didn’t have enough regulation,” says Sam Perkins, the program director at the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation, a nonprofit group based in Charlotte, North Carolina. “The last thing we need to be doing is adding any more coal ash to these sites.”

But in the name of ending the so-called “war on coal,” the Trump administration has been loosening environmental regulations designed to keep coal ash in check. The EPA has repealed restrictions on toxic waste from mountaintop-removal mining, which sends dangerous heavy metals tumbling into streams and rivers. And it has put on hold a regulation that restricted the levels of mercury, arsenic, and other pollutants coal plants can produce and prohibited certain types of chemical-laden waste from being discharged into bodies of water. The EPA estimated that the policy would have decreased coal waste by 1.4 billion pounds each year—a huge benefit to public health. But the rule would also have cost the coal industry $480 million annually, due to the new treatment systems and other equipment coal plants would need to install.

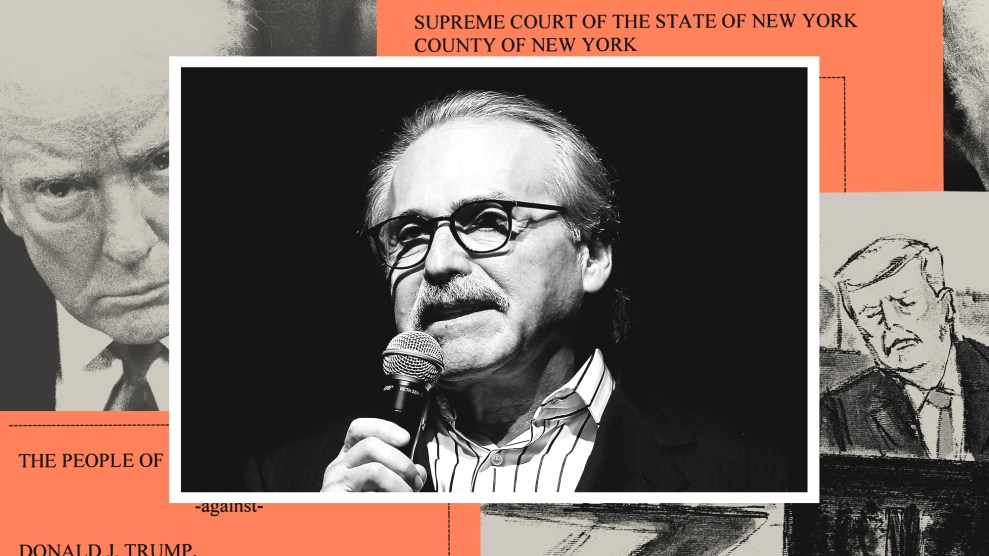

In fact, one of the administration’s most recent decisions came via a request by AES Puerto Rico. Earlier this year, the company asked EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt to pause a regulation regarding the monitoring and storage of coal ash. And in September—before Hurricane Maria hit—AES got what it wanted: Pruitt announced he would reconsider the Obama-era rule, which would have required coal companies to make sure their waste pits are not leaking or otherwise threatening human health. The regulation would have meant an existential threat for the industry. Forcing companies to monitor the pollution from their coal waste would have revealed just how great a health hazard coal ash truly represents—potentially exposing coal companies to costly class-action lawsuits that could result in payouts in the millions.

Environmentalists have consoled themselves with the knowledge that Trump can’t actually prevent coal’s downfall. Most analysts agree that coal can’t compete with alternative energy sources like natural gas, wind, and solar, which are easier and cheaper to produce. “The long-term prognosis for the coal industry in every region from now through 2050 is poor,” the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has concluded. Even Robert Murray, the founder and chief executive of America’s biggest coal firm, Murray Energy, has said that Trump should “temper his expectations” when it comes to resuscitating the coal industry. “He can’t bring them back,” Murray has said of mining jobs.

But as the crisis in Puerto Rico suggests, even a short-term surge in coal production may have lasting repercussions. By dismantling regulations that limit the amount of waste these companies produce and that enable the government to hold them accountable for polluting, Trump is compounding a public health disaster that every powerful storm surge will compound further—and that will continue long after the last coal-fired power plant shuts down.