ANDREYGUDKOV/Getty

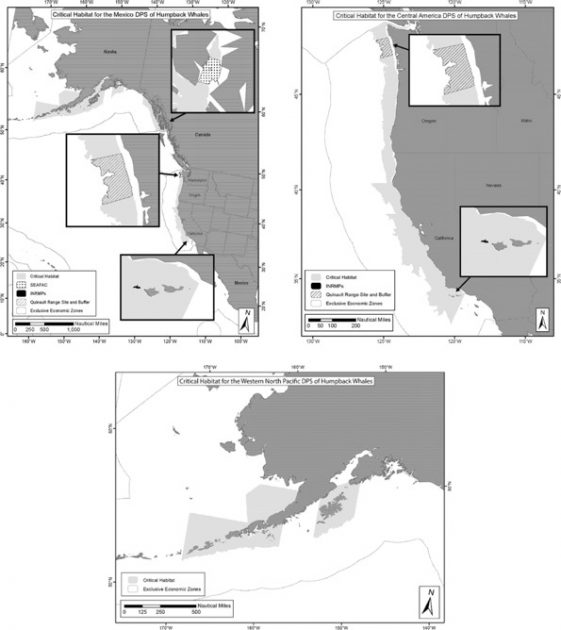

The Trump administration isn’t exactly heralded as a friend to nature’s creatures. It has, after all, rolled back Endangered Species Act protections, shrunk national monuments, and proposed opening the United States’ largest national forest up to logging and construction. But earlier this month, the administration announced it plans to designate more than 300,000 square nautical miles (that’s about 400,000 square miles) off the coasts of Alaska, California, Oregon, and Washington as critical habitat for three vulnerable humpback whale populations.

It’s great news, even if the Trump administration doesn’t seem to be totally acting of its own accord. The administration is required by law to designate critical habitat for endangered and threatened species where it is “prudent and determinable“—but it didn’t do so within the mandated timeframe that expired in late 2017, pushing environmental groups to sue and force the administration to comply with the law.

The designation comes at an urgent time for the whales. Even as most humpback populations worldwide have rebounded, a handful remain endangered or threatened. In 2016, at least 54 humpback whales were found caught in debris like rope or fishing gear off the West Coast, which that year saw its highest number of whale entanglements in recorded history, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Add to that the threats of global warming and noise pollution and the whales are in a precarious position. In one of the populations, for instance, there are fewer than 800 individual whales left, experts estimated in 2017, while other populations are made up of tens of thousands of individuals.

“We’re particularly happy that this critical habitat was proposed,” Catherine Kilduff, a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, tells Mother Jones, “because that population really needs help—if it’s going to persist.”

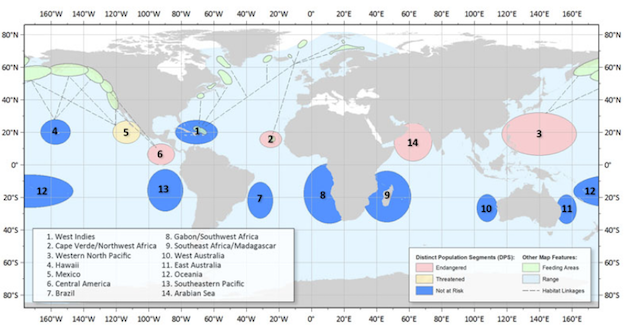

The 14 “distinct population segments” of humpback whales worldwide. The Trump administration plans to designate critical habitat for populations 3, 5, 6.

The humpback whale was hunted over the course of centuries, pushing the species to the point of near extinction; it was listed as endangered in 1973, under the Endangered Species Act, and rebounded in large part due to the institution of hunting bans. In 2016, NOAA found that nine populations no longer warranted protection under the act, but five groups (known as “distinct population segments”) remained vulnerable. The change required the federal government to create and enforce critical habitat areas for the three populations that migrate to US waters and fall under US jurisdiction for protection.

That didn’t happen right away, though. The government, which had one year to act, blew past that deadline, prompting a lawsuit from environmental groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity, in March 2018. “There weren’t any signs that the Trump administration was going to follow through with that required habitat protection,” Kilduff says. (Lisa Manning, fisheries national listing coordinator at NOAA, denied that to Mother Jones, saying that the agency was “absolutely” going to designate critical habitat. She couldn’t say if the lawsuit made the process go any faster: “Getting a critical habitat rule done is really onerous,” she says, and even more so with three separate populations.) Following the suit, in August 2018, the Trump administration reached an agreement with the environmental groups to issue the protections.

“It is unfortunate that it took legal action against the Trump administration to secure protection for endangered humpback whales, but we are pleased to move forward with our efforts to create additional marine protected areas for threatened marine life,” Todd Steiner, an ecologist and executive director of Turtle Island Restoration Network, said in a press release.

The proposed critical habitat regulation was published in early October. It is now open to public comment and the final rule is due in September 2020.

Critical habitat area for the three endangered or threatened humpback populations

NOAA/NMFS

In designating a “critical habitat,” NOAA isn’t creating a special conservation area like a marine sanctuary or marine reserve, in which the government may place strict restrictions on activities. The designation rather simply requires federal agencies to make sure any activity it funds or permits—for example, oil drilling—doesn’t harm those areas of humpback whale habitat. “If there’s a federal action that may be likely to adversely modify or destroy that critical habitat in the area that we drew,” Manning says, “then they have to consult with us.” It’s unclear how the rule will impact the fishing industry broadly, as only federally managed fisheries would be required to consult with NOAA.

Still, for endangered and threatened species, a “critical habitat” label can be, well, critical to survival. According to an analysis led by experts at the Center for Biological Diversity, species with critical habitats are “twice as likely to be improving” than those without them. Mapping out critical habitat also helps agencies in charge of conserving the species to know where to concentrate their efforts.

For marine animal activists, the new rule is a victory, but just one. Groups including the Center for Biological Diversity are still fighting the Trump administration on protections for Southern Resident killer whales, Cook Inlet beluga whales, and ice seals, among others.