With more than two-thirds of the patients the hospital sees on Medicare or Medicaid, Lincoln Community Hospital often doesn’t get full reimburDaniel Brenner/High Country News

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

When the virus that causes COVID-19 began to spread in the Western US in March, medical centers started preparing. Hospitals cleared elective surgery schedules, stocked up on supplies and retrofitted facilities to care for patients with the novel coronavirus.

But in preparing for the immediate crisis, rural hospitals worsened an ongoing one: They were running out of money, fast. Soon, they started cutting pay and laying off workers. On the rural coast of southern Oregon, almost 200 workers from the local health-care district were laid off, furloughed or had hours cut in early April. In Clarkston, Washington, 80 employees are at least temporarily out of work as the local hospital faces budget shortfalls driven by COVID-19. So far, more than 200 hospital systems in the United States have reduced staff.

For years, rural hospitals have been on the brink of financial ruin, thanks to declining rural populations and inadequate funding. Since 2010, nine Western communities, from the US-Mexico border town of Douglas, Arizona, to coastal Sitka, Alaska, have lost hospitals, leaving some rural Westerners hours from live-saving care. Without a steady influx of federal funding or an overhaul of the system, the economic consequences of the coronavirus could devastate rural health care.

Hospitals primarily make money treating privately insured patients. But with elective surgeries and specialist visits canceled and beds reserved for potential coronavirus cases, much less money is coming in. “I’ve been getting texts from hospital CEOs telling me that, by July, they’ll have no cash on hand,” said Benjamin Anderson, vice president of rural health and hospitals for the Colorado Hospital Association.

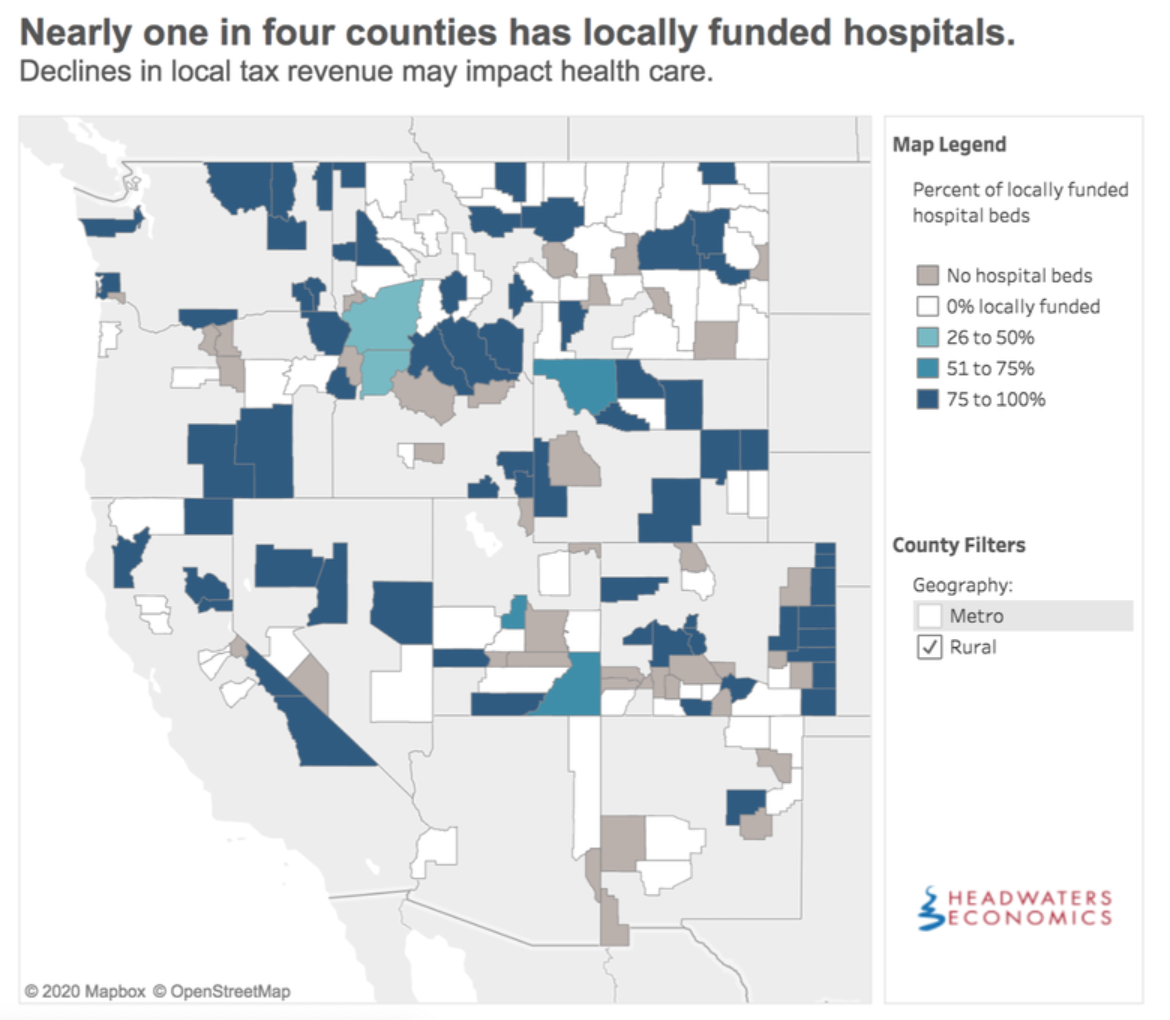

Some rural hospitals have better backstops than others. Those that are part of larger networks, like the St. Luke’s Health System in Idaho, are more resilient: When the COVID-19 outbreak hit Blaine County, Idaho, the local hospital, St. Luke’s Wood River, was able to move patients and staff around to balance the burden of what was then one of the nation’s worst per capita outbreaks. Other small hospitals are locally financed—a precarious arrangement if tax payments are delayed and revenue plummets.

While the coronavirus has intensified the economic pain rural hospitals are feeling, the underlying symptoms of the problem have been there for decades. Since the 1980s—a heyday of deregulation and cuts to the social safety net—there have been “relentless” slashes to spending, said Scott Walters, a consultant who advises hospitals on how to cut costs. An early squeeze came in 1983, when Congress changed how Medicare reimburses hospitals: New flat-rate payments from the program contributed to a wave of rural hospital closures in the 1980s and 1990s.

Congress has since tweaked payment structures and funded a new program to help rural hospitals, stanching some of the bleeding, but Medicare and Medicaid still pay only a fraction of the fees private insurers provide. That payment differential is especially felt in rural areas with older populations and higher rates of unemployment.

At Lincoln Community Hospital in Hugo, Colorado, it’s hard to make the numbers add up. At the 15-bed hospital, Medicaid payments cover only about 70 percent—and Medicare, about 85 percent—of the cost of treating patients, according to CEO Kevin Stansbury. With more than two-thirds of the patients the hospital sees on Medicare or Medicaid, Stansbury said, “We’ll struggle into the future unless we fundamentally change how rural hospitals are taken care of.”

Critics of the privatized health-care system advocate for wholesale change and nationalized universal health-care coverage. Such a system, often called Medicare for All by campaigners, would likely require a total realignment of how health care is funded, as well as major investments to keep rural hospitals running.

Still, even without sweeping changes, hospital executives and medical policy experts see ways to shore up rural hospital finances. One option is to keep medical care local by offering, and publicizing, consistent services, said Dave Mosley, a health-care policy expert for the consulting firm Guidehouse.

Some economic solutions are a direct response to the coronavirus. Lincoln Community Hospital, for example, is bringing in patients — and generating much-needed revenue —by absorbing overflow from urban hospitals. When Denver and Greeley, Colorado, faced strained resources in early April, Stansbury asked them to send patients recovering from COVID-19 to his hospital rather than to a makeshift field hospital or hotel. In the mountain town of Silverthorne, Colorado, a new walk-in orthopedic clinic opened in mid-April for patients who have injuries but aren’t sick. And many health-care providers have increased their telemedicine efforts to enable patients, especially those managing chronic diseases, to meet with their health-care providers.

In rural areas facing the pandemic without a local hospital, the situation is even tougher. It’s been 5 years since the hospital in the mining town of Tonopah, Nevada, shut down, leaving residents 100 miles from the closest emergency room.

Eljena Marie Peterson, who was the director of nursing at the Tonopah hospital and now runs a primary care practice in town, said that not having a hospital creates constant challenges. Patients have to wait for lab results that get shipped out of town, and anyone who runs out of medication on the weekend has to wait until the pharmacy reopens on Monday. When residents delay medical care, treatable diseases sometimes turn into critical conditions.

But the biggest problem is the lack of an emergency room. “In rural environments, emergencies happen,” Peterson said. She can stabilize patients at her clinic, but from there it takes a helicopter or airplane trip or an hour-and-a-half ambulance ride to reach the nearest hospital. “Anything life-threatening now, they have to be flown out,” she said. “And hopefully, they’ll make it.”