Yurok tribal attorney Amy Bowers, a friend of the author, watches her gill net while fishing for salmon on the Klamath River earlier this year.Brook Thompson

This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

For those who live on the Klamath River, its health reflects the people, positioning us on the precipice of life or death. The Klamath is magical and meandering, a river surrounded by towering redwoods and mountains. But the controversy over its water has lasted for decades, and the big questions—whether to remove four dams, who gets the water during drought years—often put farmers and Natives at odds. Meanwhile, blue-green algae blooms make the river unsafe for swimming and spread deadly diseases among fish. To outsiders, the tribes’ desire to have water for salmon survival and ceremonies might seem almost frivolous, a mere “want” compared to the “practical needs” of agriculture. Most media coverage fails to express the implications of dam removal for Indigenous people.

I grew up on the Klamath in Northern California, a member of the Yurok Tribe, canning fish with my father and grandfather, pulling in salmon and basking in the thought of doing what my ancestors did, thousands of years before me. But those days faded as the dams and drought took their toll. I was seven during the 2002 fish kill, a day forever ingrained in my mind—the eye-watering, nose-puckering stench of thousands of dead rotting salmon in the sun along the rocky shoreline of my homeland. It was the largest West Coast salmon kill in history: Over 30,000 salmon died from diseases that spread in warm waters. I learned what it felt like to lose those close to me.

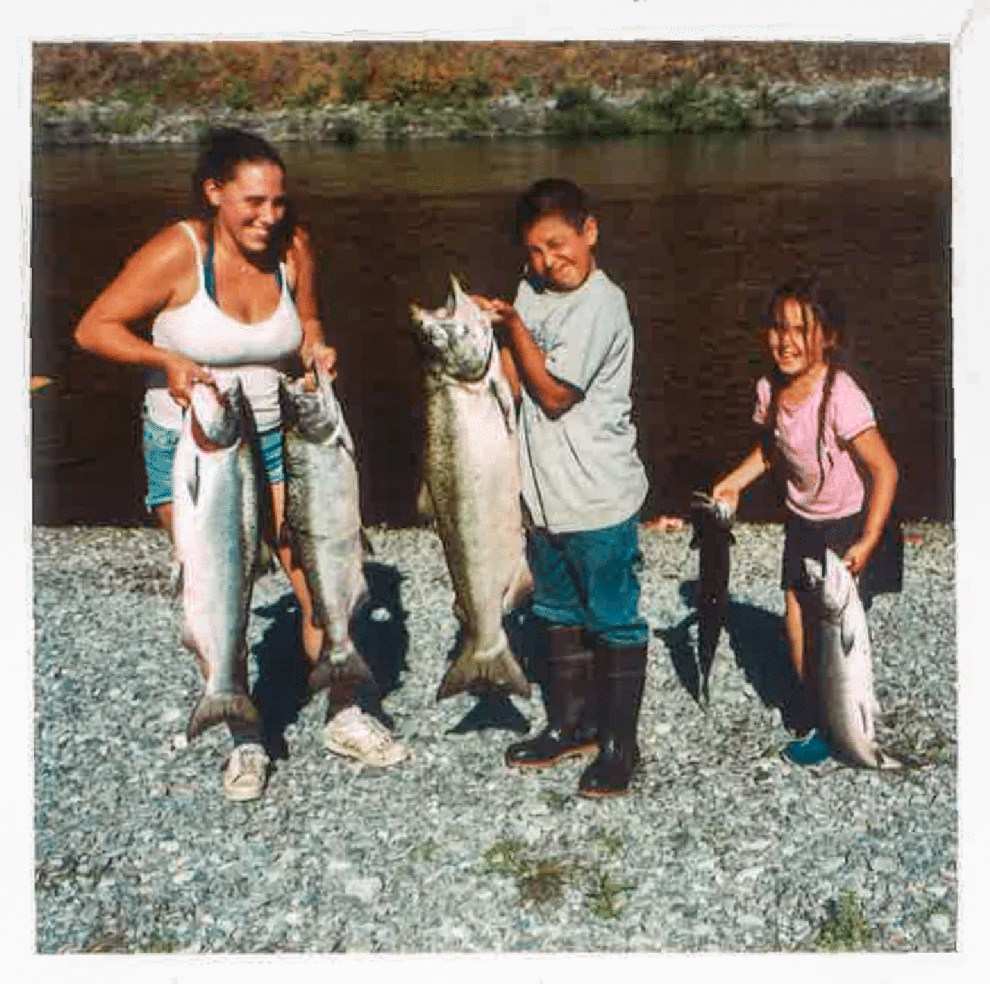

Melanie Thompson (Brook’s stepmother), Mike Carlson. and Brook Thompson with their salmon.

Courtesy of Brook Thompson

After that fish kill, everything changed; life along the river became more somber. This July, I had the privilege of catching salmon with my family again, after three years of setting my nets in vain. My dad was sick, so he wasn’t with me, but my cousins were there. My work as an environmental engineering graduate student focused on water resources has helped me respond directly to the problems on the Klamath. My greatest desire is to be a part of the solution.

My formal education took place off the reservation. I learned that the non-Indigenous world measures health solely by physical markers. But the Indigenous concept of health considers community, mental and spiritual well-being in addition to the physical factors, and it relies on people’s direct contact with land and water.

Growing up at the mouth of the river, I often had a salmon patty, scraped from the backbone, with an egg for breakfast. I snacked on the salmon my dad canned earlier that week, and several days a week had fresh salmon for dinner, fried or on a stick. A 2005 research paper described how Karuk people traditionally ate approximately 450 pounds of salmon per person per year. That 450 pounds was reduced to only five by the early 2000s. I was born in 1995, so I’ve seen a drastic reduction in my lifetime. Now, eating salmon at all is a rarity.

The nearest grocery stores are two hours to a full day away from the Klamath Reservation, and most locals cannot afford to buy fresh food there. We used to sell our salmon for $2 to $5 per pound. Today, that same salmon in the store would cost $30 to $50 per pound, meaning I could not afford the salmon I once caught. Tribal members must rely on buying processed food with a long shelf life. We believe that our intentions have real-world implications: Think about a warm, home-cooked meal prepared by someone who loves you, compared to a frozen, store-bought meal manufactured by a machine. The difference can be tasted, and the love can be felt.

The opposite is also true; food prepared by someone we don’t like can make us feel bad or sick. Even if we could afford the salmon in the supermarket, the taste is different, and it would not have the same effect on our spiritual health and well-being as fish that is caught by a friend.

The dams were built between 1911 and 1962, about the time diabetes first appeared in the Karuk Tribe. The 2005 study showed that Karuks were 21 percent more likely to have diabetes than the average U.S. citizen. And when tribal members cannot fish, hunt and gather wild food, it further reduces their daily exercise.

When Yurok people fish, we’re taught to give to others first. Sport fishermen sometimes say we are greedy, catching all the salmon; they don’t see that many of those fish will be given to our elders, the disabled and those who are sick. As my uncle, Dave Severns, a Yurok redwood canoe builder, says, it is a cultural value to give fish to your elders first; no fish ever tastes as good as the one that you provide to someone who needs it.

For Severns, salmon is less about the tasty meat than about passing down our values. We depend on each other, knowing we will not prosper individually until we all succeed as a community, strengthening our connection and mutual trust. Severns says he knows he will always have a place to stay or eat on the river, because there will always be a family willing to offer a bed and share a warm meal, however little they may have. Uncles and aunts act more like parents in the traditional tribal community, and cousins are more like siblings. It takes a community to raise a Native child.

As a child, living with my grandfather, Archie Thompson, we often had family stay over for days without warning. We believe in a type of cosmic karma described as luck. Last July, my Uncle Bobo gave me a salmon and a hug without a second thought, because he knows I seldom get to be home to fish anymore, and that my dad was not doing well. That same fish was given to him by my cousin, Toni Ray, who caught it earlier that morning. Later that day, I went down to the river. I didn’t have a boat or a net, but my cousin Pete, without hesitation, let me go in the boat with him. My family, my community, have my back, and I do anything I can for them.

Tribal communities have coexisted in managing the salmon population since time immemorial. Many of our ceremonies revolve around salmon. Most tribes on the Klamath had a First Salmon Ceremony to honor the salmon for the coming year. But they were forced to stop practicing this ceremony: Until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, such Indigenous practices were considered illegal. Meanwhile, the salmon were disappearing because of the dams, logging, overfishing and pollution.

Our ceremonies are incomplete without our salmon. The chinook and coho in this river return from the sea to their birthplaces. My people have lived on the Klamath for thousands of years, and I know that the salmon today are the descendants of those my ancestors managed. These salmon are a direct tie to my ancestors—the physical representation of their love for me. The salmon are my relatives. When the elders in the tribe are sick, they often ask for traditional foods like acorn soup and salmon. When my dad was ill recently and his family came together to bring him salmon, I knew he would benefit mentally and spiritually, as well as physically.

Despite the happiness of being with my family on the river this summer, I remember the 2002 fish kill—the salmon massacred because of decisions made by people who do not understand our connection to the water here. Each summer brings the fear that I will see more piles of dead salmon. And that fear grows with the increasingly frequent droughts. Even tribal youth who never saw that fish kill are anxious. I keep a jar of unopened canned Klamath salmon in my refrigerator. I don’t dare eat it; I’m afraid it might be my last. There’s no guarantee we’ll be able to catch salmon next year.

In 2016, the Yurok Tribe declared a state of emergency for tribal mental health. The loss of our fish contributes to our poor mental health. Many of us rely on commercial fishing for economic stability, either through selling fish or through sport-fishing tourism. Youth who cannot participate in cultural activities become depressed and turn to drugs and alcohol. Tribal members are haunted by epigenetic trauma—from the fish wars in the 1970s, when Native people were banned from fishing on the river, and from previous generations, when our grandparents were taken away to boarding schools and their culture was beaten out of them. The devastation of the river has added to the colonial impact on tribal mental health. Our problems are not inherent to our culture; Native people prospered for thousands of years. The trauma stems from generations of oppression, the loss of our water and our sovereignty.

Removing the dams will lessen the stress on the salmon, and therefore it will ease the stress we feel.

The author poses with a catch from the Klamath, c. 2006.

Courtesy of Brook Thompson

When I returned home in July, I saw the sky-blue dock that my father was married on, which I helped paint and maintain every year. Now, it’s only half its former size, with just fragments of the faded blue paint remaining. I could not even reach the fishing cabin on my family’s property, with our nets, buoys, and anchors; its door was grown over with prickly blackberry bushes that stretched up to the roof.

I wonder if my younger cousins will experience the joy of collecting salmon to give away, and the pleasure of taking a break from a long day to swim in the cool crisp water. I consider myself to be a water protector, not by choice but necessity. Instead of spending time with my family, practicing basket weaving, singing songs in Yurok and Karuk, and canning salmon, I spend my time arguing with people who do not understand the basics of Indian law and culture, people who simply cannot understand the depth of the issues I address. Even so, I know I must participate to protect my people’s right to live. My vision of protecting a healthy river and community keeps me motivated. Education, for my allies and myself, is the first step, but it’s never the last.

The Yurok people recognized the personhood of the Klamath River, but we could not give it a vote. Therefore, we must speak on behalf of the Klamath. Dam removal is the beginning of a much greater effort to restore the health of the Klamath River, the salmon and my people. After the dams are removed, there will still be issues to resolve—sedimentation and water allocation, the complicated questions around beneficial use, rights and priorities. A healthy river will require organization by those affected and support from allies. Together, we must bring Indigenous voices to the forefront to make change possible and to keep the river alive.