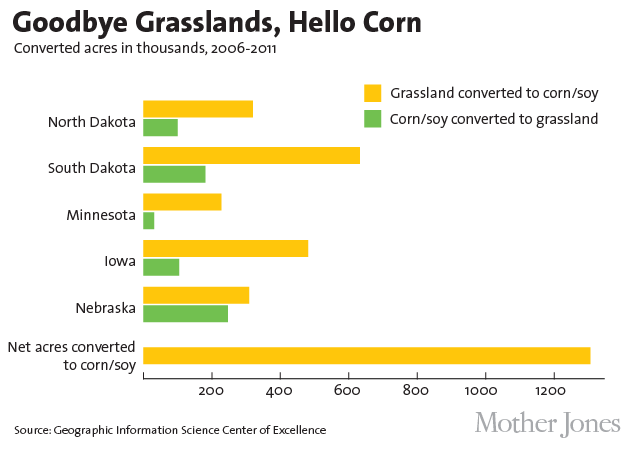

Corn and soy fields are rapidly swallowing up grassland in the western corn belt.

In a post last year, I argued that to get ready for climate change, we should push Midwestern farmers to switch a chunk of their corn land into pasture for cows. The idea came from a paper by University of Tennessee and Bard College researchers, who calculated that such a move could suck up massive amounts of carbon in soil—enough to reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture by 36 percent. In addition to the CO2 reductions, you’d also get a bunch of high-quality, grass-fed beef (which has a significantly healthier fat profile than the corn-finished stuff).

Turns out, farmers in the Midwest are doing just the opposite. Inspired by high crop prices driven up by the federal corn-ethanol program—as well as by federally subsidized crop insurance that mitigates their risk—farmers are expanding the vast carpet of corn and soy that covers the Midwest rather than retracting it. That’s the message of a new paper (PDF) by South Dakota State University researchers published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

They looked at recent land-use changes in what they call the “western corn belt”—North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska—between 2006 and 2011. What they found was that grasslands in that region are being sacrificed to the plow at a clip “comparable to deforestation rates in Brazil, Malaysia, and Indonesia.” According to the researchers, you have to go back to the 1920s and 1930s—the “era of rapid mechanization of US agriculture”—to find comparable rates of grassland loss in the region. All told, nearly 2 million acres of grassland—an area nearly the size of Rhode Island and Delaware combined—succumbed to the plow between 2006 and 2011, they found. Just 663,000 acres went from corn/soy to grassland during that period, meaning a net transfer of 1.3 million acres to the realm of King Corn.

The territory going under the plow tends to be “marginal,” the authors write—that is, much better for grazing than for crop agriculture, “characterized by high erosion risk and vulnerability to drought.”

So why would farmers plow up such risky land? Simple: Federal policy has made it a high-reward, tiny-risk proposition. Prices for corn and soy doubled in real terms between 2006 and 2011, the authors note, driven up by federal corn-ethanol mandates and relentless Wall Street speculation. Then there’s federally subsidized crop insurance, the authors add. When farmers manage to tease a decent crop out of their marginal land, they’re rewarded with high prices for their crop. But if the crop fails, subsidized insurance guarantees a decent return. Essentially, federal farm policy, through the ethanol mandate and the insurance program, is underwriting the expansion of corn and soy agriculture at precisely the time it should be shrinking.

And the stakes are high. Earlier this month, the US Department of Agriculture released a 186-page report (PDF) called “Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States.” The authors mainly concerned themselves with the question of whether our current system of corn-and-soy-dominated agriculture can be sustained in the context of rising temperatures. The answer is less than comforting. In the short term, the authors conclude, the US agricultural system is “expected to be fairly resilient to climate change.” But by mid-century, when “temperature increases are expected to exceed 1°C to 3°C and precipitation extremes intensify,” the authors expect to see significant yield declines for major US crops.

The most-major US crops, of course, are corn and soy, which now blanket nearly half of US farmland. Tragically, the USDA report never analyzes how this reliance on two crops makes us more vulnerable to climate change—or entertains the idea of making the nation more resilient and food secure by diversifying away from them.