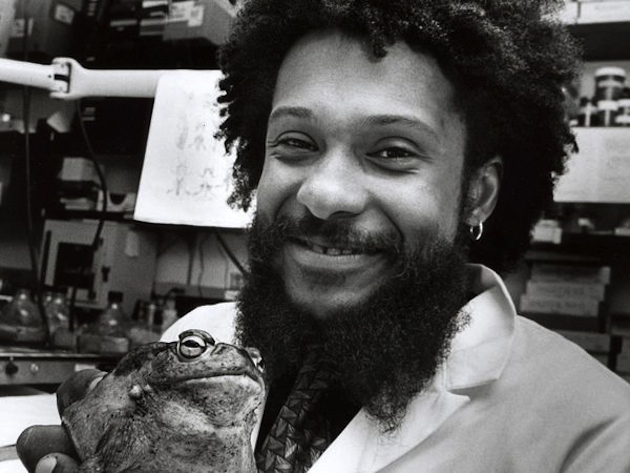

Tyrone HayesPhoto: UC Berkeley

Darnell lives deep in the basement of a life sciences building at the University of California-Berkeley, in a plastic tub on a row of stainless steel shelves. He is an African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, sometimes called the lab rat of amphibians. Like most of his species, he’s hardy and long-lived, an adept swimmer, a poor crawler, and a voracious eater. He’s a good breeder, too, having produced both children and grandchildren. There is, however, one unusual thing about Darnell.

He’s female.

Thus began Dashka Slater’s feature in the Jan./Feb. 2012 Mother Jones on Tyrone Hayes, the University of California/Berkeley biologist who has done groundbreaking research suggesting that atrazine, a widely used herbicide, can literally change frogs’ gender, even at at tiny exposure levels—a finding atrazine’s maker, Swiss agrichemical giant Syngenta, vigorously denies. This week, Darnell and other frogs under Hayes’ care have suffered another indignity, according to Hayes: he reportedly told The Chronicle of Higher Education (paywall-protected) that the university has cut off funding for his Berkeley lab. “We’re dead in the water,” Hayes told the Chronicle. He is now without funds “needed to pay for basic functional operations, such as the care of test animals,” the magazine reports. The university denies it has taken any action to defund Hayes—a spokesperson “suggested the possibility that he simply ran out of money,” the Chronicle reports.

Slater’s MoJo piece provides essential background into Hayes’ saga: the long, twisted tale about how atrazine’s maker, the Swiss agrichemical giant Syngenta, has engaged in an effort to discredit Hayes and his work. Since the publication of Slater’s blockbuster, an Illinois court has released documents shedding more light on Syngenta’s campaign against Hayes and other atrazine critics, which the pesticide maker undertook in an attempt to fight off a lawsuit by several Midwestern towns seeking redress for atrazine residues in their drinking water. (Syngenta settled that suit in 2012 by agreeing to pay out a total of $105 million to more than 1,000 communities, without admitting to culpability.)

According to an Environmental Health News piece published in June, the documents revealed an “aggressive multi-million dollar campaign that included hiring a detective agency to investigate scientists on a federal advisory panel [and] looking into the personal life of a judge.” As for Hayes, the documents showed that Syngenta had conducted research on his personal life, commissioned a psychiatric profile of him, and considered launching an investigation of his wife, Environmental Health News reports. The company’s most ironic idea, considering the news that came down this week: Syngenta entertained offering to “cut him [Hayes] in on unlimited research funds,” presumably if he iagreed to lay off on the atrazine research.

Rather than basking in unlimited research funds, Hayes now finds himself with no funds at all. He sees a possible link to the Syngenta controversy, the Chronicle reports:

Mr. Hayes said he believes some Berkeley officials, including Graham R. Fleming, vice chancellor for research, may have joined in efforts to penalize him out of a desire to protect a $25-million, five-year research agreement between Berkeley and Novartis, a parent company of Syngenta.

Berkeley officials deny this allegation—and they claim that the university hasn’t moved to cut funds from Hayes at all. I plan to dig a bit deeper into this story next week.

UPDATE: Dan Mogulof, executive director of the Strategic Communications team at Berkeley’s Office of Public Affairs, reached out to comment: “I can state categorically that the university has taken no actions against Prof Hayes.” He adds that the university’s contract with Novartis, mentioned in the Chronicle of Higher Education piece, “expired about ten years ago and was not renewed” and that “the university has no institutional ties with Syngenta.”