Don't worry, some small animals should be kept around as clickbait.<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-238590562/stock-photo-puppy-and-kitten-and-rabbit-and-bird-and-rat.html?src=dt_last_search-7">gurinaleksandr</a>/Shutterstock

When it comes to food, humans gravitate to the biggest item on the menu: overstuffed turkeys, 1,000-pound sturgeons, the fattest burger. But a new study in Science shows how our obsession with taking down the biggest prey is damaging the world’s wildlife.

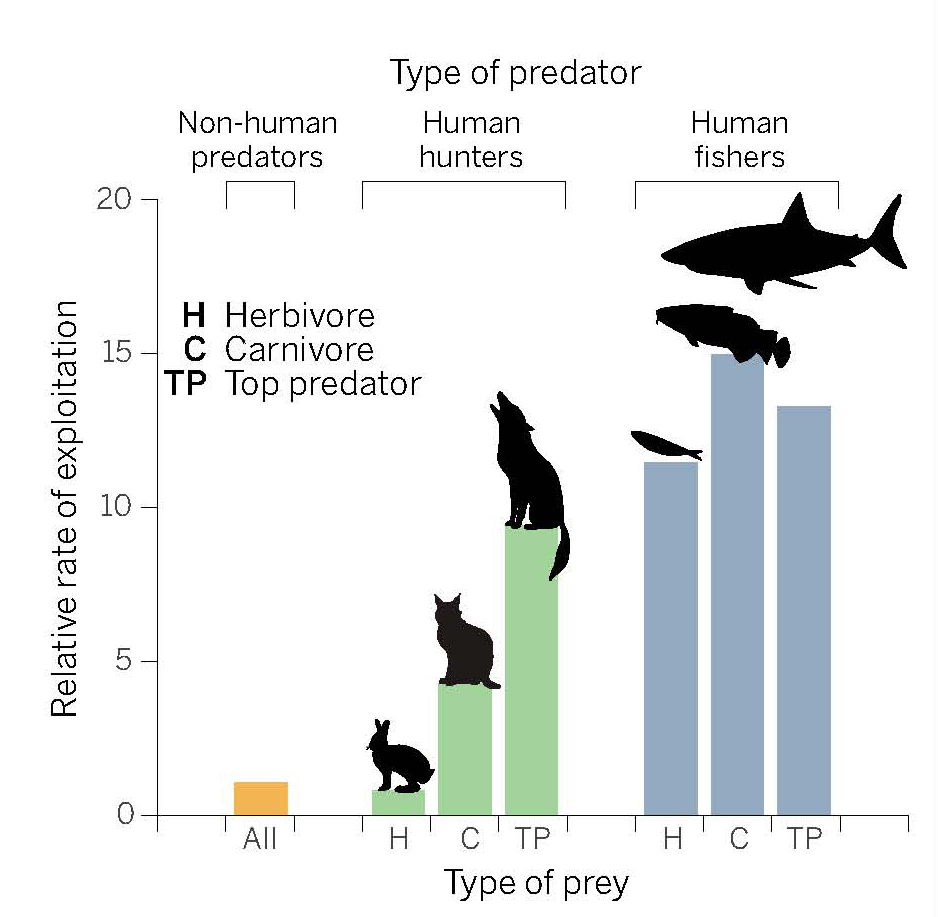

Looking at 282 marine species and 117 terrestrial mammals, researchers at the University of Victoria found that human hunters and fishers overwhelmingly target adult animals over juveniles. Driven by the prestige and financial payoff of a trophy kill or gargantuan catch—and an aversion to killing young animals that might be seen as cute—humans consume up to 14 times the amount of adult animal biomass as other predators. And that’s contributing to the swift decline of populations of large fish and land carnivores, the researchers say.

Thanks to advanced hunting tactics and tools that allow us to kill without getting too close, humans have long been able to take down massive prey (e.g., the Ice Age mammoths). But with modern advancements such as guns and the automated dragnets of industrial-scale fishing, we’ve turned into “super-predators,” the researchers write. That’s just one reason, along with the ravages of climate change and habitat destruction, we’re currently in the process of losing one in six species on Earth.

These findings go against the assumption that it’s better to target mature animals and spare younger ones. “Harvesters typically are required by law to release so-called under-sized salmon, trout, or crabs, or to set their rifle scopes on the 6-point elk and not the calves,” explained Chris Darimont, one of the study’s authors, in a call with reporters. Those regulations are in line with the paradigm of “sustainable exploitation,” the idea that killing off big adult animals that dominate a habitat will allow the young to flourish and reproduce.

The authors argue that this approach causes undesirable reverberations in the food web and, eventually, the gene pool. While the loss of the largest predators may be a boon to their prey in the short-term, ballooning populations of herbivores can devastate vegetation and have been linked to festering illnesses. While humans may raise increasingly large domesticated animals—whether by pumping cows with steroids or breeding only the fattest hogs—exploiting the largest animals in the wild can lead to tinier animals. For example, as bigger, stronger fish are plucked from the oceans, survival of the fittest undergoes a strange inversion: Smaller fish are more likely to reproduce in their absence, producing fewer, smaller offspring that are less resistant to further threats.

The authors suggest that human hunters start thinking small. In the case of fisheries, they suggest focusing on smaller catches—a process of narrowing entrances into traps and nets and using hooks to allow larger fish to evade capture. To preserve top carnivores on land, Darimont and coauthor Tom Reimchen say that tolerance—and a decreased emphasis on prized trophy kills—is the best way to bolster dwindling populations.