sturti/Getty Images

For the past two decades, the alcohol industry has pushed the message that moderate drinking provides a wealth of health benefits, and therefore should be included as part of a healthy lifestyle. As Mother Jones has reported, alcohol companies have promoted and funded studies suggesting that moderate drinking will make people live longer and ward off heart disease, diabetes, and even dementia. The industry is currently funding a $100 million clinical trial overseen by the National Institutes of Health looking at whether moderate drinking can prevent heart disease.

There are lots of reasons to be skeptical of the industry’s health claims, especially given that alcohol has been proven to raise the risk of a wide range of diseases, including cancer. Many of the studies showing that moderate drinking can be beneficial to heart health are deeply flawed. But even if it were true that alcohol could be a health tonic at moderate levels, there’s a problem with the industry’s marketing strategy: Few people who consume alcohol drink it at the level scientists define as moderate.

Surveys show that most drinkers define moderate consumption as however much they usually drink. Scientists have a different measure. The US Dietary Guidelines, published by the Department of Agriculture, define moderate drinking as having no more than one drink a day for women and two for men. (A standard drink is five ounces of wine, 12 ounces of beer, or one and a half ounces of spirits. There is a lot of debate over whether these limits might still be too high for men.) US studies on alcohol and health, including the one NIH is currently running, typically use the US Dietary Guidelines to define moderate drinking.

But most American drinkers aren’t listening to the Department of Agriculture. In 2014, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control published a study finding that two-thirds of drinkers exceeded the government drinking guidelines at least once in the previous month. That’s not surprising, given that women would be counted as exceeding the guidelines if, for example, they once had two drinks in a single day. But what’s perhaps more interesting is where it’s happening and where it isn’t.

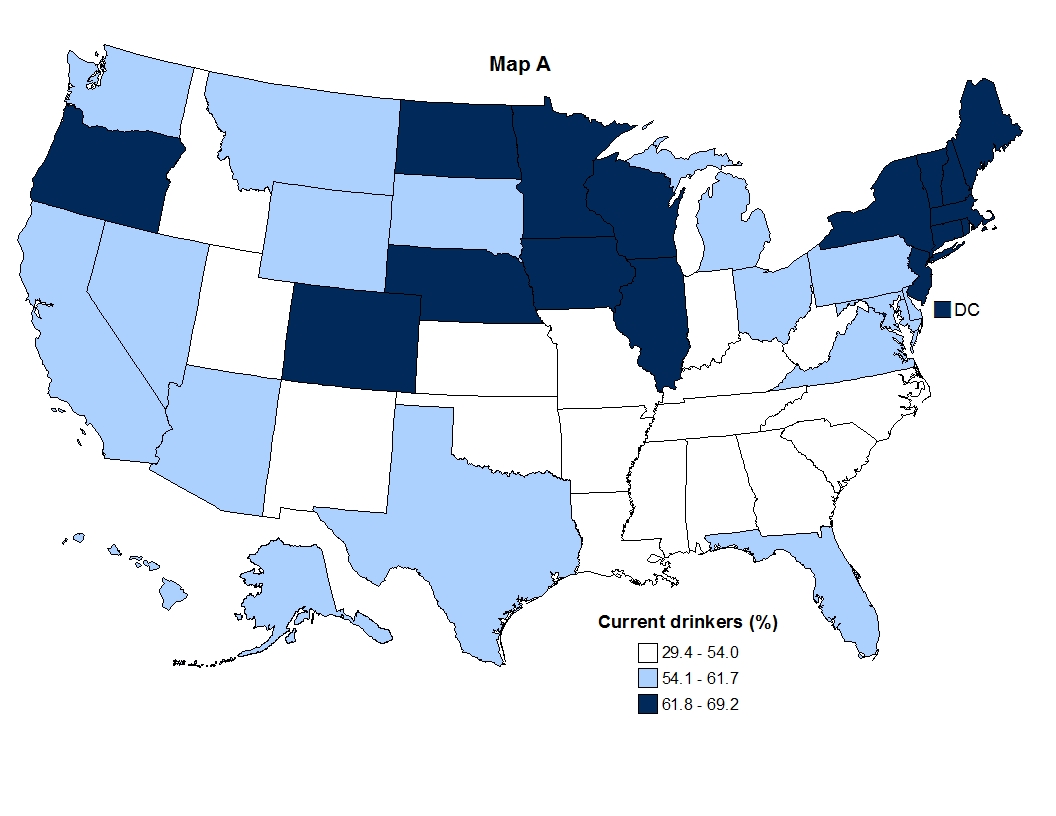

Take a look at these maps. This first one shows the national distribution of people who drink any alcohol. (About 40 percent of Americans don’t drink at all.)

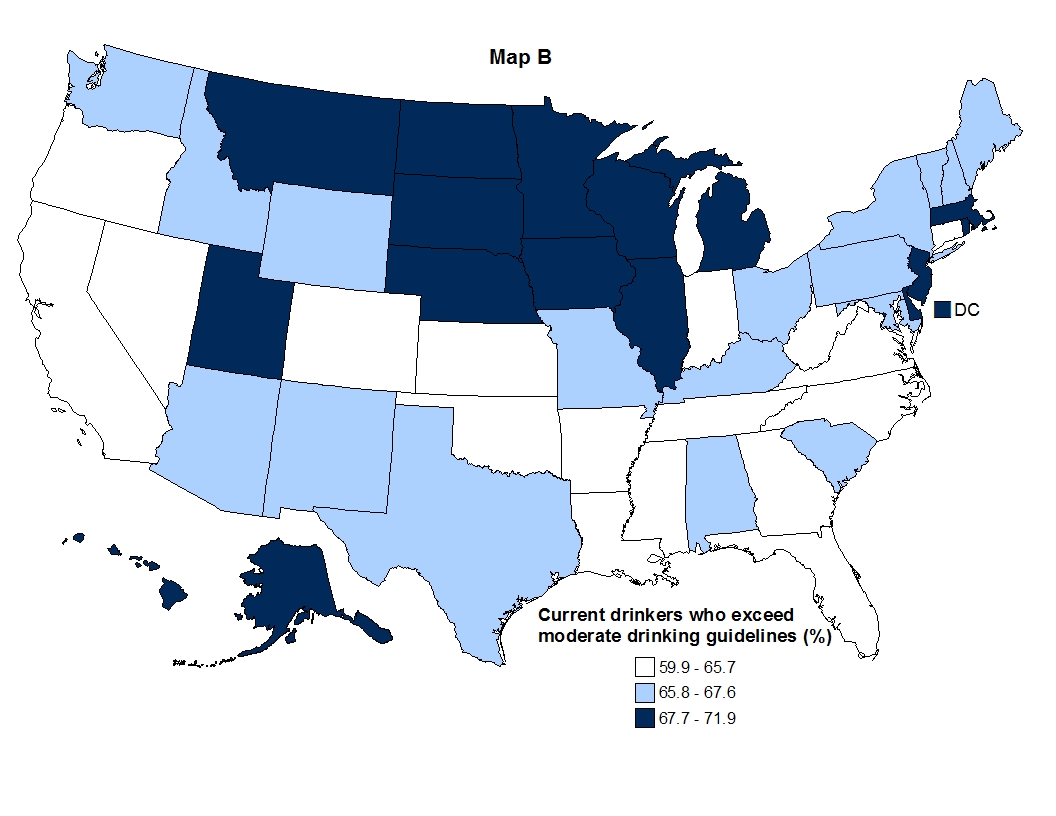

States with a lot of Mormons, like Utah and Idaho, and much of the Bible Belt in the South have low numbers of drinkers. But those figures can be deceptive. I grew up in Utah and know from experience that non-Mormons there drink enough to make up for the teetotalers next door. As this map shows, drinkers in Utah routinely bust the moderate drinking guidelines, drinking on par with those of us in DC:

Meanwhile, in nearby Colorado, where there are far more drinkers, fewer of them are drinking excessively (and not just because they’re now getting high instead; weed wasn’t legal there when the survey was conducted). In addition to geographic differences in drinking patterns, the study found big demographic variations as well. Men exceeded moderate drinking guidelines more than women, and the people most likely to exceed the guidelines were whites, college graduates, and those with household incomes over $75,000.

The study has significant implications for all of the factors that can make drinking deadly, including drunk driving, domestic violence, accidents, liver disease, and, particularly, cancer. The cancer risk from alcohol is linear: The more you drink, the more your risk goes up. Even low levels of alcohol, like those in the moderate drinking guidelines, can raise the risk of breast cancer slightly, and 15 percent of all breast cancer deaths in the United States are related to alcohol consumption.

Overall, the CDC study suggests that the public health world has a long way to go to start reducing alcohol-related cancer. The federal government funds comprehensive cancer control programs in all 50 states, DC, and a number of tribal areas. These programs craft detailed plans to help state policymakers implement evidence-based anti-cancer efforts. The plans include things like expanding access to mammography to reduce breast cancer deaths, or increasing the number of venues that ban smoking. The CDC researchers found that although most of the plans recognized alcohol as a risk factor for cancer, fewer than half included any specific proposals or even aspirations for reducing consumption. Not surprisingly, the states with the most current drinkers and the most drinkers exceeding the moderate drinking guidelines were most likely to ignore alcohol in their public health planning to combat cancer.