Niall Ferguson thinks that if deregulation is to blame for our recent financial collapse, then financial deregulation should also get the credit for the preceding 27 years of economic growth. Matt Yglesias takes a look at income growth over that period and isn’t so sure:

Niall Ferguson thinks that if deregulation is to blame for our recent financial collapse, then financial deregulation should also get the credit for the preceding 27 years of economic growth. Matt Yglesias takes a look at income growth over that period and isn’t so sure:

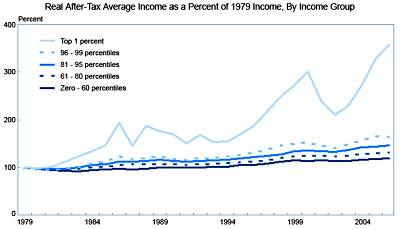

For the top one percent, that’s a pretty impressive period. For the next 19 percent, there’s something happening. But for the bottom 80 percent, there’s just very little going on in terms of real income growth. There was, however, pretty robust consumption growth fueled by the credit boom and declining savings rates. The current downturn is now threatening that and calling into question the sustainability and worth of the overall growth throughout the period.

This is a kissing cousin to the question everyone is raising these days about financial innovation. It goes like this: the basic benefit of all the financial innovation we’ve seen over the past few decades has been to make credit more easily available, and that clearly had something to do with the credit boom and subsequent bust. This in turn begs the obvious question: was it really a good idea to make credit so easily available? If the answer is no — if the only result was to mask stagnant wages and produce a fake consumption boom — then maybe all that innovation wasn’t such a hot idea in the first place.

This is rapidly becoming conventional wisdom, and Matt’s point deserves more attention as part of it. For good or ill, the modern economy is driven by middle-class consumption. If middle class wages are rising, everything is fine. They’ll consume more, debt will stay tolerable, and rich people will benefit from the growing economy. But if middle class wages are stagnant, then vast pools of money are increasingly directed toward the rich, who have a limited ability to spend it. So they end up loaning it back to the middle class, collecting economic rents along the way, and the middle class laps it up, figuring that their wage stagnation is just temporary and they’ll eventually pay all the money back.

But they don’t, of course, because today’s rich have no intention of ever allowing wage growth among the middle class. The result, eventually, is disaster.

I realize that most economists will never believe this until someone says the same thing accompanied by several dozen pages of equations with lots of Greek characters. So can someone please get cracking on that?