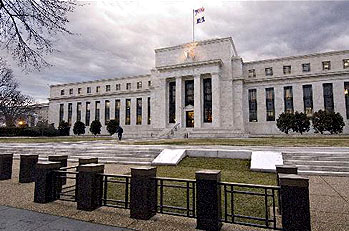

Via Tyler Cowen, Randall Kroszner writes in the Financial Times about the delicate role the Fed has to play as we (hopefully) exit the current recession. If they keep monetary policy loose too long, they risk long-term inflation. But if they tighten too fast, they risk cutting off the recovery too soon, as they did in 1937. What to do?

Via Tyler Cowen, Randall Kroszner writes in the Financial Times about the delicate role the Fed has to play as we (hopefully) exit the current recession. If they keep monetary policy loose too long, they risk long-term inflation. But if they tighten too fast, they risk cutting off the recovery too soon, as they did in 1937. What to do?

Just last autumn, Congress gave the Fed a new tool that will play a crucial role as it exits from its unusually accommodative monetary policy: the ability to pay interest on reserves. Previously, a recovery would mean more opportunities for banks to lend and so they would draw down non-interest-bearing reserves and expand credit and hence the money supply. Interest on reserves, however, can cut that logic short by providing incentives for banks to hold reserve balances rather than lend them out, as the Federal funds rate target rises. The Fed now has a greater control over the reserve choices of banks because it can raise the return on reserves relative to banks’ lending opportunities, and thereby better manage credit and money growth in a recovery.

The basic idea here is simple: if the Fed raises the rate it pays on bank reserves, banks will park money at the Fed. That reduces the amount of money they lend out. Cut the rate and banks will pull their money out and find a better use for it. Lending will increase.

Fine. That makes sense and always has, as long as you trust the Fed to handle this particular monetary knob properly. But what I still don’t get is why you’d turn this knob up during a crisis, as the Fed did last year. That reduced bank lending at a time when credit had already dropped off a cliff and was threatening to choke off the economy completely. Is there some triple bank shot (no pun intended) here that I’m not getting? Did the Fed figure that banks just flatly weren’t going to loan out funds no matter what, so they might as well pay them interest as a backdoor way of recapitalizing them? Or what? I’m still confused.