Ezra Klein on the new recommendations suggesting women should start getting mammograms at age 50, not age 40:

You could hardly imagine a better example of why cost control is so hard: This was a recommendation from an institution with no actual power that was based entirely on accepted medical evidence. Cost was not a component in the analysis. This is simply the data on whether mammograms make sense for most women between 40 and 50, not whether they’re “worth” doing as opposed to other expenditures.

And the political outcry has been deafening.

Beyond the purely scientific aspect of the debate, one of the notable things about the reaction to the new mammography guidelines is the way it highlights how passionate minorities drive so many public debates. The USPSTF recommendation is based on large-scale costs vs. large-scale benefits, but the conversation that followed has been based mostly on personal stories. And you’ll never hear any personal stories about the costs. Only the benefits. Virtually all of the personal testimony over the past few days has been from women who either contracted breast cancer in their 40s and were saved by a mammogram, or who have unusual conditions that require unusual monitoring. Obviously, if you fall into one of these categories you’re going to feel very, very strongly about the benefits of early mammography.

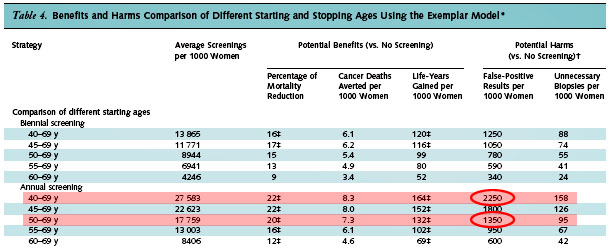

And the millions of women who (if the USPSTF is to be believed) got mammograms in their 40s and suffered ill effects of one kind of another? For the most part those effects were relatively minor, so nobody feels motivated to write op-eds about them. But they’re surprisingly widespread: the report suggests that the cumulative risk of a false positive result is over 50% for women who get annual mammograms between 40-49. That’s a lot of false positives, a lot of extra biopsies, and a lot of unnecessary panic.

It’s a close call, and annual testing may still be worth it. (The USPSTF continues to recommend it for women with a family history, genetic prediliction, or environmental risks.) That’s a largely personal choice. But as with most political arguments, the public debate on this is being driven mostly not by dispassionate science, but by a passionate minority. That’s democracy for you.

UPDATE: Via comments, it turns out that women who get false positives are occasionally motivated to write op-eds about the experience after all. Here’s one from Andrea Stone.