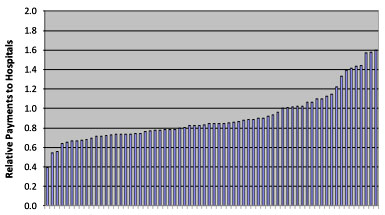

Martha Coakley may have lost her Senate race against Scott Brown last January, but she’s still attorney general of Massachussetts. So a couple of weeks ago she released a report about the wide variance in prices for medical services throughout the state, which the chart on the right illustrates in a nutshell. It’s for one of the state’s major insurers (Harvard Pilgrim) and it shows astonishing variation in payment rates. There’s a 4x difference from the lowest paid to the highest paid hospital.

Martha Coakley may have lost her Senate race against Scott Brown last January, but she’s still attorney general of Massachussetts. So a couple of weeks ago she released a report about the wide variance in prices for medical services throughout the state, which the chart on the right illustrates in a nutshell. It’s for one of the state’s major insurers (Harvard Pilgrim) and it shows astonishing variation in payment rates. There’s a 4x difference from the lowest paid to the highest paid hospital.

Why is this? We’ll get to that, but first let’s walk through all the things that don’t explain the differences. Here’s what the report found:

- Wide disparities in price are not explained by differences in quality of care.

- Wide disparities in prices and total medical expenses are not explained by the relative sickness of the population being served or the complexity of the care provided.

- Wide disparities in prices are not explained by the extent to which a provider cares for a large portion of patients on Medicare or Medicaid.

- Wide disparities in prices are not explained by whether a provider is an academic teaching or research facility.

- Wide disparities in prices are not explained by differences in hospital costs of delivering similar services at similar facilities.

So this astonishing variation isn’t explained by quality of care, older/sicker patients, Medicare rates, or even differences in underlying costs. What could possibly be left?

Answer: leverage. If a hospital group owns most of the hospitals in an area, it’s got the whip hand and can demand higher payment rates. Insurers can’t afford to be  shut out of entire market, so they have to pay up. Conversely, if a single insurer is dominant in an area with lots of providers, it can squeeze the local hospitals, who can’t afford to be dropped.

shut out of entire market, so they have to pay up. Conversely, if a single insurer is dominant in an area with lots of providers, it can squeeze the local hospitals, who can’t afford to be dropped.

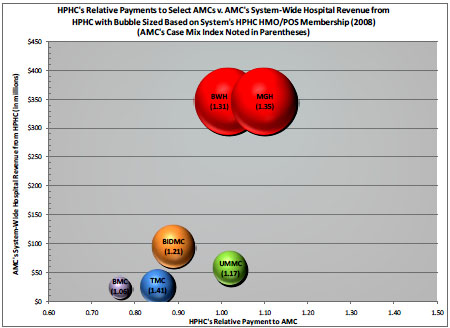

The chart on the right demonstrates the relationship. It’s also for Harvard Pilgrim, and it shows payment rates to six similar adult academic medical centers. The small ones get low rates, the big ones get high rates. What’s worse, there’s a vicious cycle in which high-cost hospitals use their higher rates to fund more expansion, giving them even more leverage:

Higher priced hospitals are gaining market share at the expense of lower priced hospitals, which are losing volume….[Highly paid hopspitals] are able to build new buildings, purchase new equipment and technology, and add to their cost structure. In contrast, hospitals with lower prices are unable to put comparable resources toward building maintenance or equipment acquisition….This results in a loss of volume to better capitalized, more expensive hospitals.

….As patient volume shifts from lower-priced to higher-priced hospitals, overall health care costs increase because those patients are now receiving their care in the higher-priced setting….[Low-cost] providers continue to lose volume to higher-priced hospitals, making it increasingly difficult for them to remain competitive, or sometimes even viable.

This is, obviously, just one study in one state — and just as obviously, it’s not the whole story. But it’s suggestive of a widespread problem, and one that’s not just confined to hospital bargaining power. Coakley’s report, for example, showed that a big part of her state’s increase in medical costs was due to rising prices, not increased utilization of services. At the same time, a recent study in Health Affairs shows that doctors who own a stake in outpatient surgery centers operate on twice as many patients as non-owners. In both cases — whether it’s extracting higher prices or driving up utilization of questionable surgery — it’s money that’s motivating healthcare choices, not good medicine.