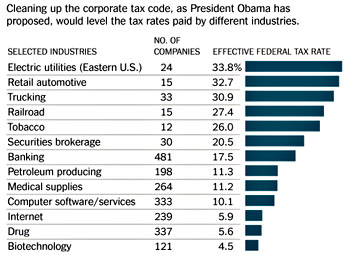

The New York Times has a pretty good primer on corporate tax reform today, and it includes the chart on the right showing the different rates that various industries pay thanks to the tax breaks, subsidies, and loopholes that they’ve lobbied for over the years. Jon Chait comments:

The New York Times has a pretty good primer on corporate tax reform today, and it includes the chart on the right showing the different rates that various industries pay thanks to the tax breaks, subsidies, and loopholes that they’ve lobbied for over the years. Jon Chait comments:

Guess what? The interest of the companies benefiting from loopholes outweighs the interest of the companies that would like lower rates. If nothing else, loss aversion will drive the loophole beneficiaries to lobby harder than non-beneficiaries. My prediction: nothing happens.

He’s probably right, and this is a profound demonstration of just how far right the Republican Party has moved over the past couple of decades and how much more power the business community has amassed. After all, as Bruce Bartlett reminds us today, the idea of lowering rates but eliminating loopholes in the corporate tax code managed to get bipartisan support as recently as 25 years ago during the administration of conservative hero Ronald Reagan. Today, though, it’s a nonstarter:

Republicans claim they are for it, but they steadfastly refuse to name a single existing tax provision that is worth getting rid of; they are only for tax rate cuts and that is the sum total of their contribution to the tax reform debate….The other factor in Republicans’ thinking is just cynical politics….Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and the man who, more than anyone else, lays down the Republican line on all tax issues, told me this when I asked him about coming up with offsets to pay for tax reform: “I recommend taking the corporate rate to 25 percent. The Dems can suggest tax hikes if they believe they need to ‘make up’ revenue. That is a bipartisan division of labor.”

The political trap is obvious. Any actual reform that would increase revenue will be relentlessly attacked by Republicans as a tax increase and they will quickly send out fundraising letters to whatever group or industry is affected, requesting campaign donations to prevent the Democrats from raising their taxes. No mention will be made by Republicans of the idea that the reforms would be coupled with tax rate reductions in a revenue-neutral manner that neither raises nor lowers net tax revenue in the aggregate. Unfortunately, this strategy will doom any hope of tax reform. No Democrat is going to put forward any revenue-raisers under these circumstances.

I’ve always been cautious about taking any lessons from the passage of corporate tax reform in 1986. It was, in some ways, sui generis, a sort of miraculous bipartisan stand against corporate interests that’s just very, very rare. And yet: it happened. Twenty-five years ago conservative Republicans were willing to team up with Democrats to do something that was good for the country, and neither side backed down because of either corporate pressure or an unwillingness to allow the other side a victory. It was, in a way, an existence proof that this kind of thing was once possible.

In theory, there’s no reason it couldn’t happen again. Democrats are probably willing to go along, and base broadening is, officially anyway, something that conservatives favor. But in real life, Republicans are less willing to work across the aisle these days and Democrats are far more responsive to corporate pressure than they were in the 80s — which is, I suppose, just a longwinded way of saying that American politics is broken and big business reigns supreme. But it’s a very concrete way of saying it, and it lends itself to an almost quantitative assessment. The fate of corporate tax reform is sort of a bellwether for the state of our political system, and I suspect our system is so broken that it will die without even getting a serious hearing.