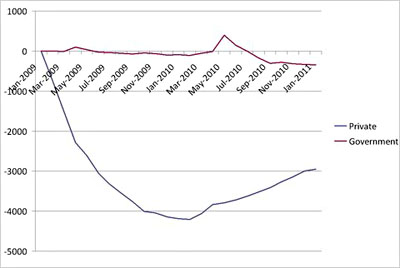

Ezra Klein reprints this chart from David Leonhardt, which shows that there’s been no surge in government employment over the past two years (the short blip in 2010 is from temporary census hiring), and makes this comment:

Ezra Klein reprints this chart from David Leonhardt, which shows that there’s been no surge in government employment over the past two years (the short blip in 2010 is from temporary census hiring), and makes this comment:

But I also think the chart above speaks to what’s driving the events in Wisconsin: a perception that people in the “real” economy have suffered greatly, while public workers have been cosseted by their union contracts, their lobbying might and stimulus dollars. And there’s some truth to that. The public sector basically sat out the first year of the recession.

Unfortunately, Ezra is almost certainly right that this perception informs the way a lot of people think about economic downturns. It’s an unfortunate example of the way we like to view recessions as morality plays rather than macroeconomic events to be dealt with as efficiently as possible.

Start with the private sector. Why did companies shed so many workers? Answer: not because their workers were slothful layabouts, but because business was bad. If your widget sales decline by 10%, you don’t need as many sales people, you don’t need to run as many shifts in the factory, and you don’t need as many accounts receivable clerks. So you lay them off. You don’t really have any choice if you want to stay in business, but it’s still unfortunate since people without jobs don’t buy widgets, which just makes your situation even worse. If you could manage it, it would be pretty helpful if no one got laid off at all.

Now how about the public sector? It’s exactly the opposite because the public sector isn’t in the business of selling things. If the economy tanks, that doesn’t mean there are fewer fires, less crime, or a smaller number of kids in school. That’s why cops, firefighters, and teachers don’t get laid off. Not because they’re a bunch of cosseted union goons, but because the demand for their services is just as high as it was before the recession. In some cases, in fact, it might be higher. There’s actually more demand during recessions for clerks to handle unemployment applications or Medicaid reimbursements than there is during boom times.

And it’s a good thing, too, since, as Ezra says, “The worst thing for an unemployed person is another unemployed person. It means more competition for job openings, lower wages and less job security.” The best outcome for everyone would be for government to employ more people during recessions and to keep their wages high. This would reduce competition for jobs and help keep consumption from falling, which is why, in a perfect world, the federal government would be running big deficits in order to fund the ability of states to keep the lights on.

But the fact that this makes sense doesn’t mean most people see it this way. We’re biologically wired to be envious of anyone who has things better than us, and there’s never any shortage of demagogues to stoke that envy. So we demand that if we’re going to suffer, then everyone has to suffer. And guess what? That’s exactly what happens.