Adam Ozimek points today to a study of KIPP charter schools that finds good outcomes for KIPP students and concludes that none of it is attributable to “skimming.” That is, it’s not the case that KIPP schools are getting  good scores because poor students are prodded to leave at higher rates than good students.

good scores because poor students are prodded to leave at higher rates than good students.

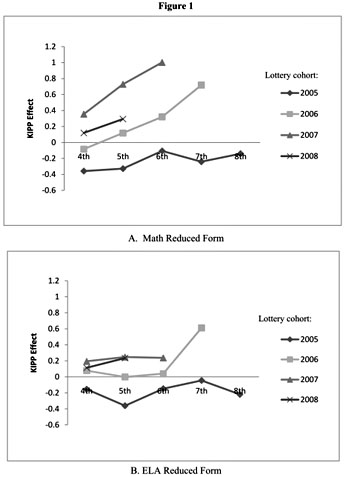

This is obviously good news, though, as usual, there are reasons to be cautious. For one thing, the sample size of this study is extremely small: one school. For another, although the math results seem to be very good and very robust, the reading scores are much less certain. As the chart on the right shows, the 2005 cohort of kids actually shows a negative reading result at every grade level, and the more recent cohorts show positive but modest results with the exception of a single data point (the 2006 cohort’s fourth year). Still, the results overall are generally positive and they confirm other studies that have also found good results from KIPP schools. What’s more, KIPP’s effectiveness, if anything, seems to be higher for low-income kids than for higher-income kids.

But something has been on my mind for a while about these studies, and this is a good chance to toss it out. This isn’t related to my longstanding skepticism that the KIPP model can ever be scaled enough to be a broad-based solution, and it’s not really meant to be a criticism of KIPP at all. In fact, all the evidence I’ve seen suggests that KIPP really does work well.

Rather, it’s about the way these studies are done. Basically, you want to compare test results of charter kids to test results of public school kids, but first you want to make sure the kids themselves are similar. If charter kids, on average, are just smarter than public school kids, then good test results don’t mean anything. One way of doing this is to control for the kinds of things that we think matter for success in school: income level, gender, race, English proficiency, etc. The problem is that no matter how many variables you control for, you never know for sure if you’re really controlling for everything important.

Because of this, the gold standard for charter school research is to study schools that rely on lotteries to decide who gets in and who doesn’t. Since selection is random, there’s no difference between the kids who get in and the kids who don’t. Nor are there systematic differences between the parents: all of them care enough about their children’s education to apply to a charter school in the first place. So if the charter kids do better than the public school kids, it’s almost certainly due to the schools themselves, not some inherent difference in either the children or their families.

But ever since seeing Waiting for Superman, I’ve had a nagging question about this. That documentary, if it’s accurate, made it clear that parents who apply to charter schools are almost desperately anxious for their kids to get in. In fact, many of them view it as practically their only chance to escape their local schools and get their kids a real education. The ones who lose the lottery are profoundly deflated.

So here’s my question: is it possible that the mere act of losing out in a charter school lottery changes some parents’ behavior? With their hopes dashed, do they give up? Do they gradually stop taking an interest in their child’s education? Do they become fatalistic about the prospect of success and stop prodding their kids to do their homework, behave in class, and get to school on time? And if some substantial fraction of them do, how much overall impact does this have on the aggregate test scores of the lottery-losing children?

I know this is a virtually unanswerable question, and I don’t mean to use it as some kind of all-purpose, non-falsifiable objection to charter schools. I’m just curious. It never really occurred to me before I saw Superman, and I understand that the film may have overdramatized things for effect. Still, the losing parents sure did seem crushed. I have no idea how you could study this effectively, but I’d sure like to know whether the mere act of losing a charter school lottery has a negative effect on kids all by itself.