Back when Proposition 8 — the anti-gay marriage initiative — was in court, one of the arguments made against it was that it represented a fundamental revision to the California constitution, not a mere amendment. As such, it  should have required two-thirds approval from both houses of the legislature plus a majority of the public.

should have required two-thirds approval from both houses of the legislature plus a majority of the public.

Gay rights supporters lost that argument, but Charles Young, the former chancellor of UCLA, had a brainstorm. Maybe Prop 8 wasn’t a fundamental revision, but how about Proposition 13?

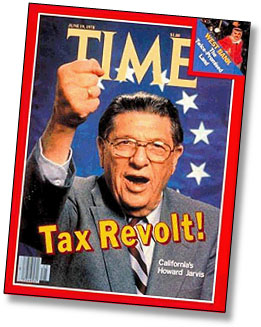

Passed at a time when property taxes were sharply on the rise and California was running a surplus, Proposition 13 limited property taxes to 1% of a property’s value and restricted the annual increases on assessed values. Those provisions seem like a traditional amendment — they change or add specific rules within a larger constitutional set of provisions. But Proposition 13 also required that “any change in state statute which results in a taxpayer paying a higher tax” must be approved by two-thirds of both houses of the Legislature.

That language has had a profound impact on the power of the executive and the Legislature. The power that it constrains — the authority to raise public funds — is among the most fundamental of government. And the requirement gives more weight to some legislators — and, by extension, their constituents. As the lawsuit notes, “legislators opposing a tax increase are given the functional equivalent of more votes than those legislators who favor such proposals.”

Young and William Norris, a retired U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals judge, have filed a lawsuit making exactly this case. Merits aside, I’d be pretty surprised if any court were willing to overturn Prop 13 after more than 30 years on the books. But then again, the merits of the case, frankly, seem pretty strong. Moving from majority rule to supermajority rule strikes me as a pretty fundamental revision of the basic plan of government, especially when it applies to a core function of government like raising money to fund itself. Californians may be in for a surprise once Young and Norris get their day in court.

Not an entirely unpleasant surprise, either. Sure, everyone likes having their property taxes capped. But Prop 13 has had a helluva lot of unintended consequences aside from simply making it hard to raise revenue efficiently. It’s also fundamentally changed the relationship between the state and local communities, putting far more power in Sacramento than in the past. It’s created permanent special treatment for businesses, which tend to own property for a long time and therefore pay lower average property taxes than the rest of us. And since revenue has to come from somewhere, it’s created an insane crazy quilt of “fees” that often make little sense but can be put in place by majority vote. Getting rid of all that would be no bad thing, even if it does mean that a few people might see their taxes raised more easily than before. Stay tuned.