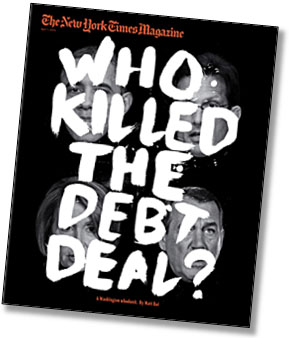

In the New York Times Magazine this weekend, Matt Bai has yet another gigantic story about what really happened last year to kill the “grand bargain” deficit deal between Barack Obama and John Boehner. When I saw it, I sighed. Do I really want to read another one of these things? Luckily, I can now easily  download monster pieces like this to my iPad and then read them in the comfort of my easy chair, so I ended up reading it after all. There was, as near as I can tell, one genuinely significant new item of information in the piece.

download monster pieces like this to my iPad and then read them in the comfort of my easy chair, so I ended up reading it after all. There was, as near as I can tell, one genuinely significant new item of information in the piece.

First, a nickel summary. Last July, after several weeks of on-again-off-again negotiation, Boehner and Obama reached a kinda-sorta handshake agreement on a deficit deal that would raise $800 billion in revenue (though this part of the deal was shaky) and cut $1.7 trillion in spending. But then the Gang of Six, a bipartisan group of Democratic and Republican senators, announced a deal of their own that included about $2 trillion in extra revenue. A substantial number of Republican senators expressed support for this package, and Obama immediately understood that Democrats in Congress would revolt if he asked them to approve a package with far smaller revenue increases than even a lot of Republicans were willing to concede. So he went back to Boehner and asked for a deal that included both more revenue and deeper spending cuts. At that point the deal fell apart.

So what happened? Boehner’s story is that Obama reneged on a handshake deal. Obama’s story is that no final deal had ever been agreed to. It’s true that he pushed for more revenue concessions all the way to the end, but he was also willing to go back to the original deal if the bigger package turned out to be a nonstarter. In the end, though, the problem was that Boehner couldn’t get his own caucus to agree to any deal that included additional revenue.

So who’s right? Some of both, of course. Obama did push for extra revenue after the Gang of Six announcement, but it turns out that Boehner wasn’t quite as shocked by Obama’s proposal as he later pretended:

By the next morning, both men were facing rebellions on the Hill. The Times’s Carl Hulse and Jackie Calmes had written a front-page article disclosing the existence of the new round of talks and asserting that a deal was very near….And yet, even then, as powerful contingents in both parties rose up to oppose a deal that was already tenuous, negotiations were proceeding amiably and apace. At the White House that Thursday morning, July 21, Jackson, Loper, Nabors, Sperling and Lew, among other aides, agreed to set aside the revenue question and focus on hammering out some of the smaller discrepancies in the two offers.

….The speaker’s story about this moment in the negotiations has always been remarkably consistent….The additional revenue that Obama demanded was a “nonstarter,” he says….Boehner had no choice but to walk away from the negotiations….[But] Boehner wanted a deal badly enough to stay at the table for 48 hours after Obama “moved the goal posts,” which casts doubt on his claim that this breach of trust was an obvious dealbreaker.

….As part of a broader proposal, which has remained until now a closely held secret, Boehner was apparently open to meeting the president at the new, higher revenue target — a concession that most likely would have meant abandoning the idea that no taxes would have to be raised. Had that counteroffer ever made it to Obama’s desk, it’s not hard to imagine that the grand bargain would have gotten done within 24 hours, at great political risk to both men….What happened, instead, based on extensive reporting, was this: Boehner raised the possibility of his counteroffer with Cantor on that Thursday afternoon, and Cantor dismissed the suggestion out of hand.

….Boehner talked to Obama a short while later. The president laid out the options as he would later relay them to Reid and Pelosi: more revenue and a bigger package, or the $800 billion and a smaller one. Boehner heard him out, but by then he must have known, from his discussions with Cantor and others, that neither option was going anywhere in his own caucus. It was one thing to risk your speakership on a grand bargain, which Boehner had without question been willing and even eager to do. It was another thing to throw that speakership away with little chance of success, which is what Obama was now asking of him.

Bai makes it pretty clear that although the Gang of Six really did throw a monkey wrench into the negotiations, it was Eric Cantor who definitively killed the deal, making it clear to Boehner that the Republican caucus would flatly not be willing to support any deal that had even a hint of additional revenue. Toward the end, when Obama famously put a call into Boehner that went unanswered for an entire day, it wasn’t because Boehner had “run out of time” and felt that Obama was unlikely to budge, as he now says:

Boehner didn’t want to talk with Obama because he feared exactly the opposite — that Obama would respond by offering him the original terms from the previous Sunday, and that Boehner would then find himself trapped. He had to now know that, despite his sense of himself as a persuasive statesman who could get his caucus to follow his lead, he couldn’t get any deal past even his own leadership. It was safer for Boehner to walk away and accuse Obama of having sabotaged the deal than to risk that Obama would retreat to the earlier terms on which they had agreed, forcing the speaker to backtrack himself.

So there you have it. There are enough moving parts to give both sides a decent story to tell, but the real story is the one that’s been obvious all along: the current Republican caucus in the House flatly won’t support any budget deal that includes even a cent in new taxes. Boehner kept hoping maybe he could fudge that, but eventually Eric Cantor put the hammer down and told him in no uncertain terms that he was living in a dreamworld. That’s what killed the debt deal.