Stories about problems in the eurozone often compare the “industrious” north to the “carefree” south. Or maybe the “easy-going” south. Or the “sun-drenched” south. The word lazy is seldom actually used, but it’s almost always implied. They’re just a bunch of sluggards down in Italy and Spain and Greece and Portugal!

As it happens, this isn’t true. According to OECD figures, Italians average about 34 hours of work per week. Portugal clocks in at 33 and Spain at 32. The industrious French, by contrast, work an average of only 30 hours per week. Germans punch in 27 hours per week and the Dutch 26.

The problem isn’t laziness, it’s lack of productivity. Italians simply don’t produce as much per hour as Germans, which means that in order to be competitive they have to be paid less. But over the past decade, thanks to hot currency flows into the south, inflation in Europe’s periphery has been high and wages have risen. A currency devaluation could take care of this, but since Germans and Italians all use the euro  these days, that’s not possible. Nonetheless, one way or another, labor costs need to go up in Germany and France and down in Italy and Spain.

these days, that’s not possible. Nonetheless, one way or another, labor costs need to go up in Germany and France and down in Italy and Spain.

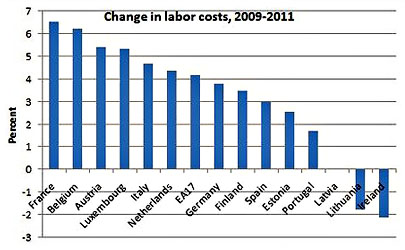

Unfortunately, as Paul Krugman points out this morning, that’s just not happening. Not nearly fast enough anyway. Labor costs in Italy have actually risen more than in Germany, and even in Spain and Portugal, which have risen less, the difference is tiny. Spain has made up less than one percentage point on Germany and only about three percentage points on France. At that rate, relative labor costs won’t get to where they need to be for decades.

“You can argue that adjustment is happening here,” says Krugman, “but it’s painfully slow — and not remotely fast enough to avert catastrophe on the current course.” This is true. At the same time, it’s also true, as Tyler Cowen points out, that “There does not exist any coherent, workable, political incentive-compatible plan whereby [periphery] governments borrow more, spend more, and ‘invest for growth.'” Something along the lines of Jay Shambaugh’s plan might work, but nothing along those lines is yet on offer, and Europe simply doesn’t have decades before something gives and the eurozone collapses. The question is, how long do they have?