In a recent column about the limitations of data, David Brooks wrote this about the debate over how effective economic stimulus has been: “As far as I know not a single major player in  this debate has been persuaded by data to switch sides.” This got Bob Somerby’s attention. Had he ever changed his mind based on data? He says yes: the first time he actually looked for himself at NAEP testing data on schoolchildren and discovered what it actually showed:

this debate has been persuaded by data to switch sides.” This got Bob Somerby’s attention. Had he ever changed his mind based on data? He says yes: the first time he actually looked for himself at NAEP testing data on schoolchildren and discovered what it actually showed:

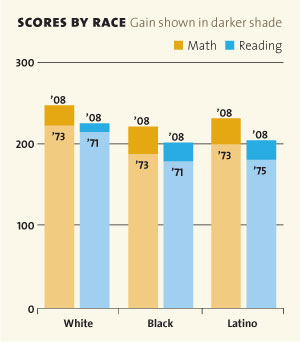

We were stunned by what we saw there. We saw that, according to this gold standard program, black kids had been making large progress in reading and math down through the years. (Hispanic kids too.)

Like everyone else who reads newspapers, we had never heard this. Like everyone else who reads newspapers, we had endlessly heard that our schools were awful and getting worse—that absolutely nothing was working.

….That progress, if real, is astounding. But thanks to the mountain of liberal indifference, the public has never been told. Very few people have ever heard that our low-income and minority kids seem to be doing much better in school.

This is one of the reasons why Obama will face great odds if he tries to sell universal preschool. To this day, the public is constantly told that nothing works. Why would they want to pay for universal preschool if nothing else ever has worked?

I guess I sort of plead guilty to this. Like Bob, I was also surprised the first time I really started to dig into test score data: it showed pretty clearly that we’ve made consistent progress over the past three decades, especially at the elementary school level. It turns out that American schools aren’t in terminal decline. At the same time, years of dipping into the ed reform literature has made me very cynical about faddish interventions. Virtually none of them really seem to hold up when you test them with bigger sample sizes, longer time series, or better studies.

I feel differently about pre-K interventions for a couple of reasons. First, we aren’t talking about marginal improvements to an existing system. In many cases, we’re talking about replacing nothing with something. The returns are much more likely to be large when you’re starting from zero.

Second, the evidence in favor of pre-K seems to be stronger, even though it suffers from some of the same limitations of K-12 programs. It’s true that we won’t know for sure what (if anything) works until we perform rigorous testing on large-scale programs that have been run for years, but the evidence we have so far suggests to me that we’re likely to see measurable benefits. It also, frankly, just seems like the right thing to do. Rich and middle-class parents already provide this kind of thing for their kids, and in a country as wealthy as ours, I see no excuse for not giving poorer parents at least the same opportunities for their kids.

So yes: I suppose that cynicism about K-12 interventions doesn’t help to gain public support for pre-K programs. Mea culpa. But the answer isn’t to lower our evidentiary standards. The answer is to make sure we do rigorous analysis of K-12 and pre-K programs. In the end, the public will never be willing to consistently fund these programs unless we do.