Our story so far: Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff have been telling us for the past few years that high levels of government debt are bad for future growth. But is that true? There’s certainly a correlation between debt and growth, but is there causation? Or is there some third factor that causes both high debt and low growth?

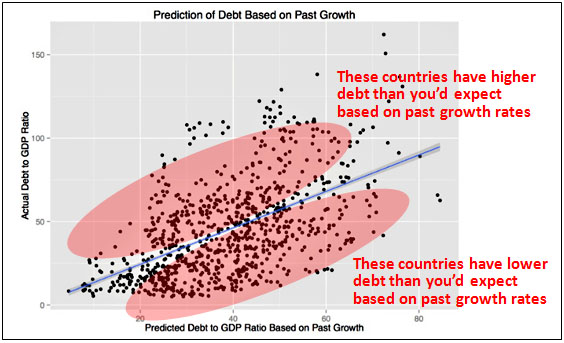

There’s already some evidence from UMass economist Arindrajit Dube that R&R get the causality backward: It’s not that high debt causes low growth, but that low growth causes high debt. Today, Miles Kimball and Yichuan Wang of the University of Michigan take a closer look at this and try to tease out what’s causing what. To start with, using R&R’s dataset, they plot past growth rates vs. present debt for various time periods. This allows them to produce a formula that predicts debt levels based on past growth. Then they plot actual debt vs. predicted debt. The regression line running through the middle of the data tells us the average level of national debt you’d expect based on past growth rates:

Obviously some countries have higher debt than you’d expect based on their past growth, and some have lower debt. So the next question is: Do countries with higher than expected debt levels at a particular point in time have lower future growth than countries with lower than expected debt? If debt truly has an independent effect on growth, you’d certainly think so.

But it turns out this isn’t the case. Not even slightly. Debt simply doesn’t matter. Basically, low growth in the past predicts low growth in the future. That’s all there is to it. However, low growth in the past also predicts high debt, which can fool you into thinking it’s the debt that’s causing low growth in the future. But it’s not.

Now, Kimball and Wang are still no fans of high debt. If your debt is high compared to other countries, the bond markets will probably punish you. What’s more, “the big problem with debt is that the only ways to avoid paying it back or paying interest on it forever are national bankruptcy or hyper-inflation. And unless the borrowed money is spent in ways that foster economic growth in a big way, paying it back or paying interest on it forever will mean future pain in the form of higher taxes or lower spending.” It’s possible, of course, to spend money in ways that foster economic growth, but they believe that most conventional stimulus spending isn’t spent that way and therefore isn’t very useful.

Nonetheless, it isn’t harmful either. “Our bottom line from this analysis, and the thinking we have been able to articulate above, is this: Done carefully, debt is not damning. Debt is just debt.”