Justin Wolfers points us today to a paper by Eric Chyn, one of his PhD students, that investigates the benefits to children of moving away from bad neighborhoods. In order to avoid contaminating effects, Chyn followed children whose families had been forced out of public housing projects when the buildings they lived in were demolished. Then he compared them to families who stayed put.

This is a genuinely random selection since some families were forced to move, and others weren’t, based solely on whether their building happened to be scheduled for demolition. Chyn found a substantial effect: when they grew up, children who moved were 9 percent more likely to be employed and had average annual earnings 16 percent higher than children who stayed.

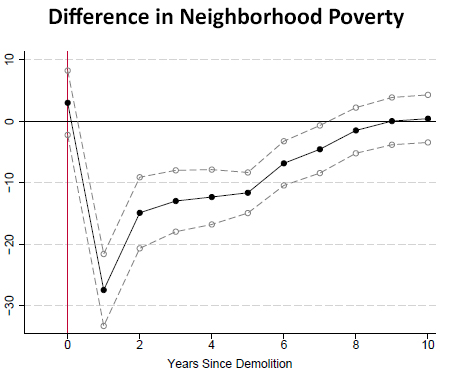

But there are a couple of interesting charts in his paper that bear further study. The first one shows the level of neighborhood poverty for movers compared to stayers:

Immediately after moving, families end up in neighborhoods with considerably less poverty than the housing projects they came from. But within five years the effect is nearly gone, and after eight years it’s completely gone. In one sense, this is bad news: it means that even families that move to better neighborhoods eventually just drift back into high-poverty areas. But in another sense it’s good news: the effect on kids is substantial even though they typically spend only about five years in a better neighborhood.

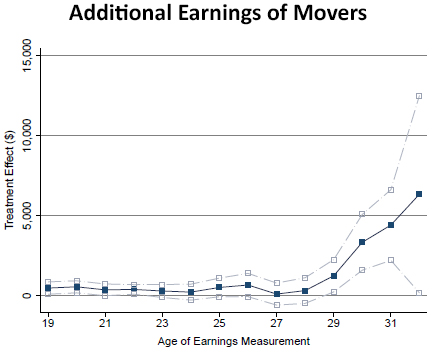

Next up is a chart that shows the adult earnings of children who moved out of bad neighborhoods:

The odd thing here is that there’s essentially zero effect up through age 28. Then there’s a sudden uptick, and by age 32 the movers are earning upwards of $5,000 more than stayers. But why? A higher starting point, or a steady increase, would be understandable. But why a sudden and dramatic change right at age 28? If this is really true, and not just an artifact of sample size or study design, it deserves further study.