It’s not really worth writing very much about the whole Harris-Biden busing hoo-ha. Forced busing for purposes of addressing discrimination is 50 years in the past and no one seriously thinks it’s going to make a comeback. But today is a dex day, so I’m feeling energized to write about a couple of things that maybe haven’t gotten enough attention. In one sense, none of it is important because it’s so long in the past, but in another sense that’s exactly why it is important. Even a lot of people my age have forgotten about this stuff, and people younger than me never knew it at all.

The first thing to remember is that busing was primarily a Southern thing. The South fought it for a long time, but eventually court rulings forced them to integrate their schools and busing was a part of that. This happened in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Elsewhere, for all the brawling and backlash it produced, forced busing barely even happened. There were several high-profile cities that adopted busing—Boston and Los Angeles most famously—and the opposition in these cities was savage. This opposition made lots of headlines and created powerful political movements, but the truth is that not all that many kids were ever bused. Outside of the South, the number of cities with forced busing programs was small, and most of those programs lasted no more than a decade. In Los Angeles it lasted only three years.¹ And even many whites who were sympathetic to busing eventually came to the conclusion that it was ineffective. If you used a technical definition of segregation that merely compared school populations to the overall population of school-age children, you could say it worked, but the acceleration of white flight was so pronounced that most school districts weren’t any more integrated in a real sense even after years of busing. Here’s an example from Minnesota:

In August, 1981…Minneapolis Tribune writer Greg Pinney reviewed the progress and the changes in Minneapolis public schools since August, 1971: “No longer does the city have ‘minority schools’ in the center and ‘white schools’ everywhere else. Minority and white students have been spread around to such an extent that it is difficult to put those labels on any school anymore.” There were other major changes in the district as well. Total enrollment of whites declined from 58,000 students in 1971 to 29,000 students in 1981, a decline of 50%; and minority enrollment increased from 8,700 in 1971 to 13,000 in 1981, an increase of 70%.

In terms of actual interracial exposure—i.e., significant numbers of whites and blacks attending the same schools—this chart shows what happened across the country:

This comes from an article in the William & Mary Law Review written in 1995, when scholars were first trying to make sense of what had happened once busing was mostly in the past. What it shows is that desegration genuinely worked in the South: interracial exposure increased substantially over just a few years in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Conversely, nothing happened outside the South. Literally nothing. In fact, over time schools became slightly less integrated. The effect of white flight overwhelmed the effect of busing and other anti-discrimination measures.

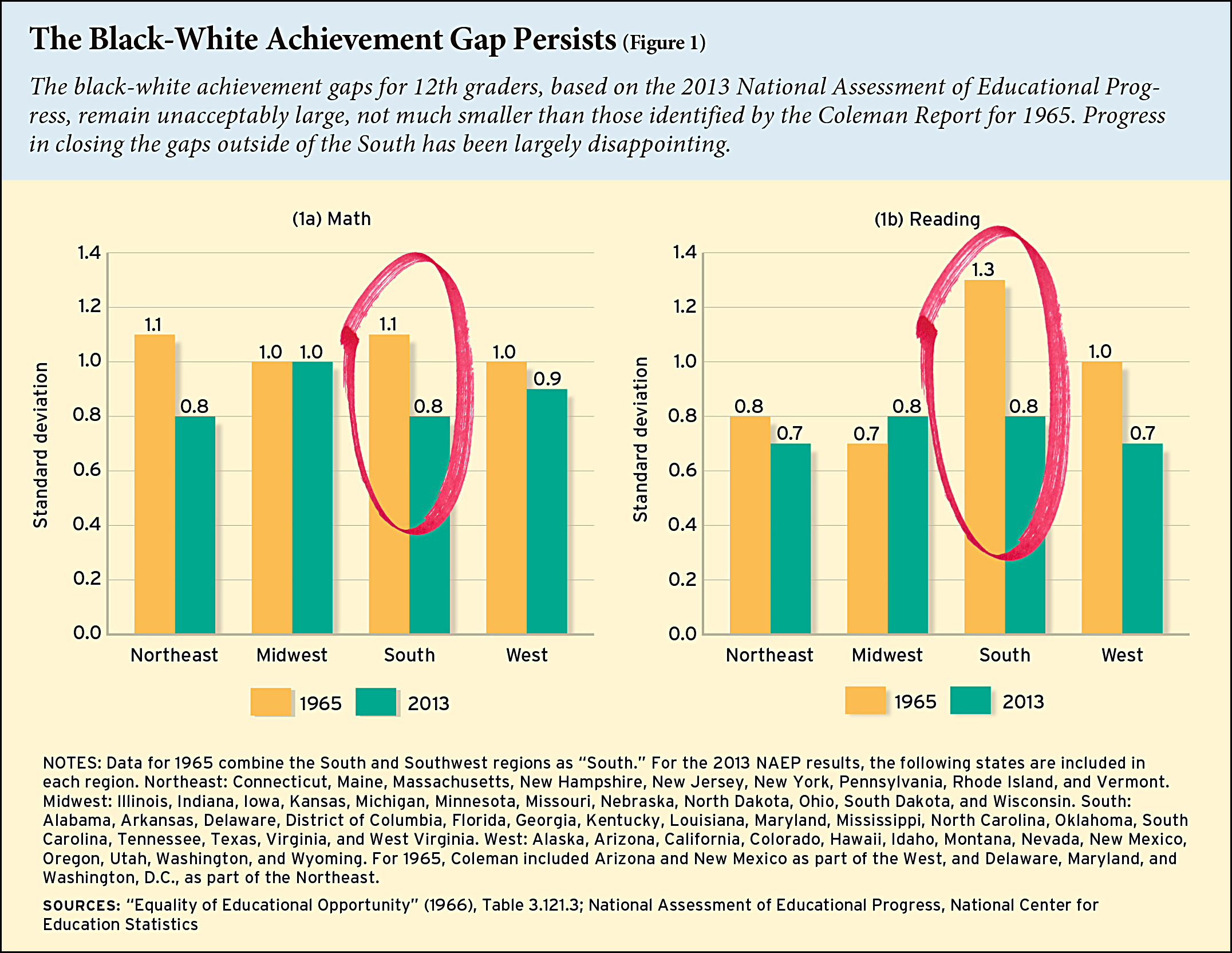

However, the fact that only the South integrated their schools in any significant way gives us a way of figuring out whether integration worked. That is, did it help black kids perform better in school? And did it do any harm to white kids? First, take a look at this chart:

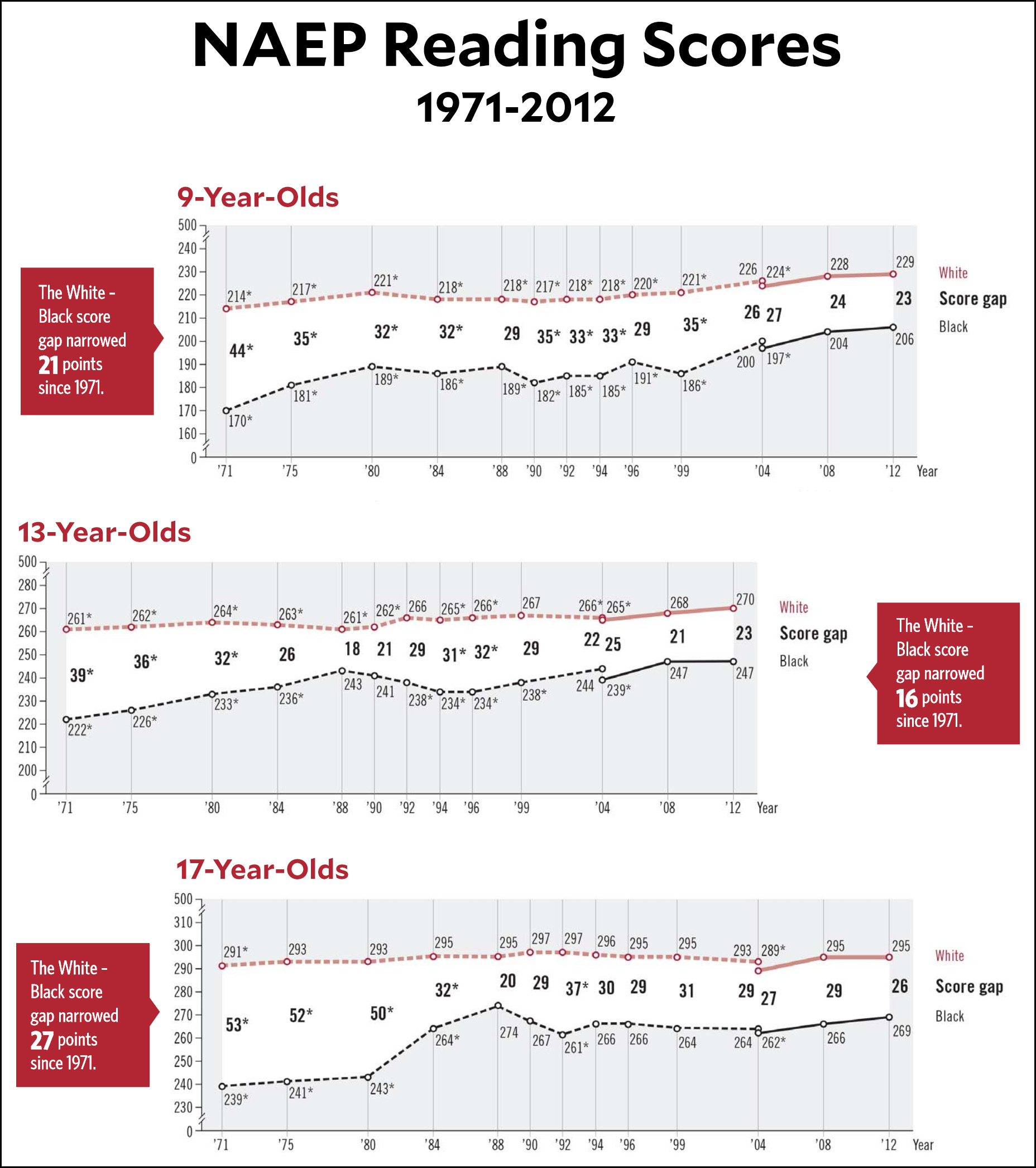

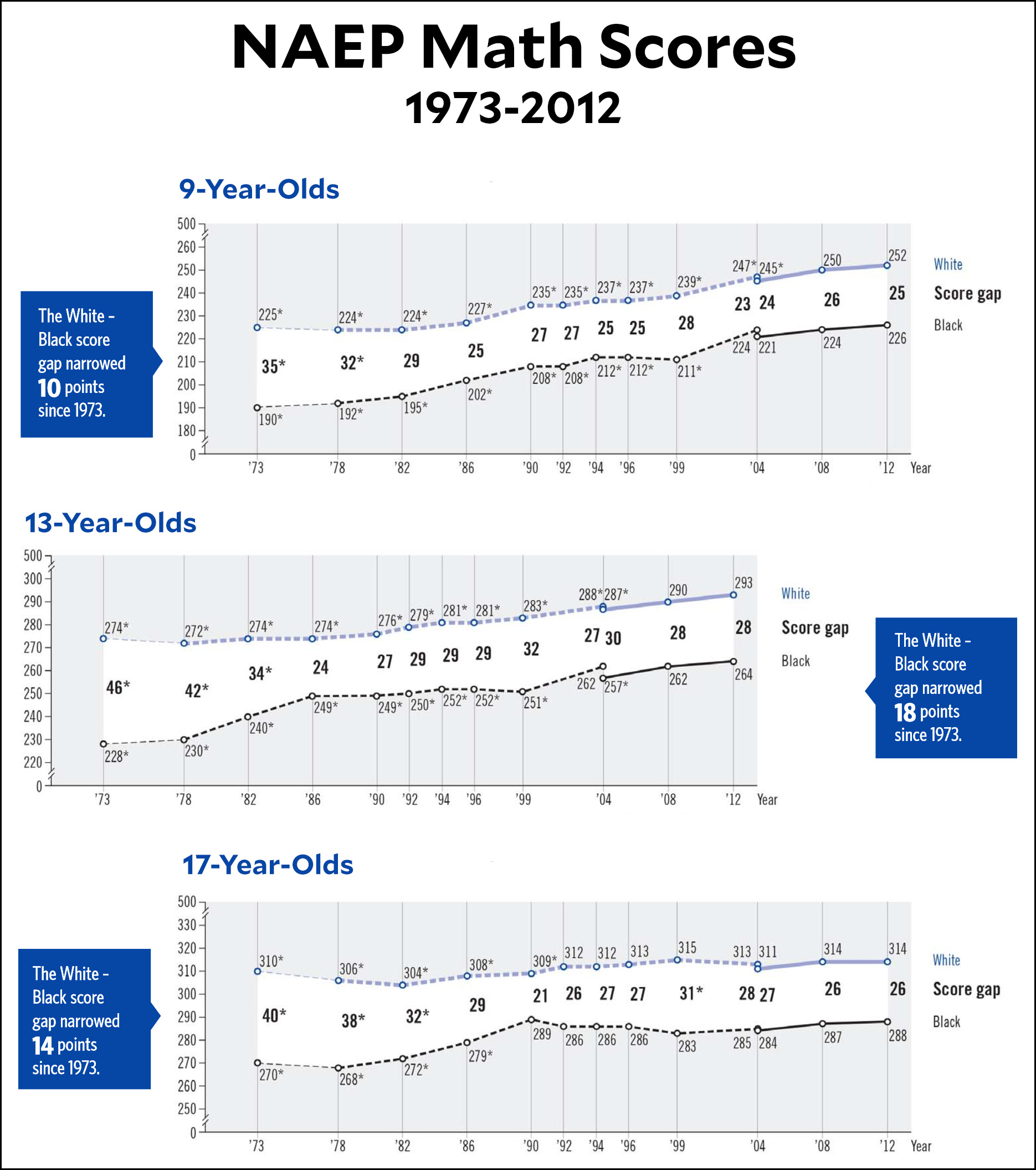

Roughly speaking, the only region that showed a significant reduction in the black-white testing gap was the South—which was also the only region that showed a reduction in segregation. But when did the testing gap narrow? And did it happen by raising black test scores or lowering white scores? I don’t have this broken down by region, but here’s the answer for the US as a whole:

These charts show two things. First, the black-white gap narrowed most strongly in the ’70s and ’80s, just when integration efforts were at their strongest. Second, the gaps narrowed solely because black kids did better. The scores of white kids were consistently either flat or up, not down. This is national data, but it’s still a very strong indicator that integration really did improve black test scores while doing no harm to whites.

There was surprisingly little rigorous research into busing back when it was happening, which makes it difficult 50 years later to say for sure how well it worked—for whatever definition of “worked” you happen to prefer. Still, the evidence we do have points in a consistent direction: integration of public schools helped black kids and probably would have had an even stronger impact if states outside the South had been forced to do it more and do it longer.²

¹In Los Angeles, as in many other places, busing was replaced by voluntary measures like magnet schools, which were designed to be so attractive that both black and white parents would want their kids bused to them. Voluntary measures, however, were never enough to overcome the desire of white parents to keep their kids in local schools that were predominantly white.

²In fairness, busing was different in the South, where black and white kids often lived in nearby neighborhoods and were bused to segregated schools during the Jim Crow era. To a large extent, the South could achieve integration simply by eliminating busing and letting kids of all races attend their local schools. Also, segregation in the South was as much a rural issue as an urban one, and even urban areas in the South were smaller than the big cities of the north. Where busing was used to reduce segregation, the bus rides were often relatively short. Outside the South, things were very different. Neighborhoods were so segregated that the only way to integrate schools was to implement busing from the start, often requiring very long bus rides within large cities and their outlying areas. Along with the acceleration of white flight, this is one of the reasons that forced busing outside the South was never all that popular with black as well as white parents.