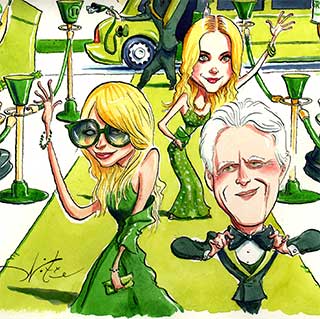

Illustration: Michael Witte

as tourists ogled Johnny Depp’s fossilized footprints in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on a mild day last December, a couple hundred entertainment industry insiders gathered on the other side of Hollywood Boulevard to celebrate their shrinking environmental footprints. Inside the first Hollywood Goes Green conference, attendees heard about how Evan Almighty had neutralized its carbon emissions and how the 2007 Academy Awards had been “greened” right down to the recycled toilet paper. Producers delivered elevator pitches for ecofriendly reality shows; an nbc exec praised her bosses at General Electric for being “great green activists.” Willie Nelson’s biodiesel supplier drummed up business, and former Dallas oilman-turned-avocado-farmer Larry Hagman boasted about the size of his solar array. After hours, the fate of the earth was considered over organic vodka cocktails mixed in bicycle-powered blenders.

A day earlier, Al Gore had accepted his half of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, affirming his role as the patron saint of the burgeoning environmental-media complex. An Inconvenient Truth was a wake-up call for the film industry, whose previous climate-change disaster flick was the apocalyptically absurd The Day After Tomorrow. Though fewer than 5 million people saw AIT (as it’s known in the biz), those are extraordinary numbers for a documentary film. AIT proved not only that audiences would sit through a glorified PowerPoint presentation billed as “the most terrifying film you will ever see,” but also that a low-budget, feel-bad movie could become the 21st-century version of Silent Spring.

But don’t expect to see AIT 2: Judgment Day in a theater near you anytime soon. As Tinseltown steps up as the public-relations wing of the environmental movement, it’s following a very different script than the one written by Gore and decades of environmental activists before him. It’s turning the traditional messages of the environmental movement on their heads, replacing existential anxiety with a relentlessly feel-good, prime-time-ready version of saving the planet. Like many Hollywood adaptations, it will pull out all the stops to make you laugh, cry, and kiss a few bucks goodbye. And even if it stays true to its source material, a lot of the substance and sweep of the original will wind up on the cutting-room floor. In Hollywood, the truth may be inconvenient, but the solutions are anything but.

This happy-ending vision of environmentalism was on full display at Hollywood Goes Green. The current state of the world, speakers reminded conference-goers, was not so much a crisis demanding difficult choices as an opportunity for some painless—and even profitable—lifestyle upgrades. Ed Begley Jr., whose reality show Living With Ed chronicles the trials and tribulations of low-impact living, spoke passionately about the need to combat global warming yet soft-pedaled his radical way of life. He proudly described taking the L.A. Metro to the event but reassured the audience that it need not go to such extremes. Instead, he emphasized the simple things it could do at home or on a movie set—like printing scripts on recycled paper or convincing talent to carpool with the crew. “We can do this,” he repeated, mantralike. It was a far cry from the call for shared sacrifice that Gore had just reiterated in Norway, where he’d exhorted the world to “abandon the conceit that individual, isolated, private actions are the answer.” But if Begley—a man who bought his first electric car in 1970—wasn’t going to lay down a little collective guilt trip, no one was.

Of course, guilt-free environmentalism is appealing to an industry that craves publicity for its good deeds yet is hypersensitive about accusations of limousine liberalism and greenwashing. A 2006 ucla study found that the TV and film business is one of the Los Angeles area’s top producers of air pollutants and carbon emissions, mostly due to transportation. Tom Cruise’s annual fuel bill is reportedly $1 million. (“It’s the dirtiest [industry] because it’s the biggest,” retorted Begley a bit defensively.) Which is not to say that Prius-driving stars aren’t serious about the environment, just that they want their commitment to be judged by the long-standing code of celebrity activism—that doing something, no matter how slight, insulates them from criticism of their otherwise profligate way of life. As Laurie David, a producer of An Inconvenient Truth, told the online magazine Grist, “Sure, I have a big house”—her PR people won’t reveal just how big—”but I use it to gather hundreds of people for eco-salons…[T]he point is not necessarily what more you could do—we could all do more—the point is that we do our part.”

The entertainment media have obligingly rolled out the green carpet, following the fawning lead set by Vanity Fair‘s annual green issue. The affirmation is heaped on by “green gossip” blogs such as Ecorazzi and the Green Carpet as well as the Sundance Channel’s wonderfully titled, Lexus-sponsored ode to celebrity environmentalists, Ecoists. And the ecoboosting continues with the Environmental Media Association, a nonprofit that exists to fete activists such as Nicole Richie and Mary-Kate Olsen and lets producers nominate their own shows and movies for its Green Seal awards based on self-reported achievements in recycling, organic catering, and carbon-offset buying. The amount spent on carbon offsets for a typical big-budget film is only around $10,000, but the publicity is priceless: Months after Evan Almighty flopped, its website still touts its status as “the first big movie comedy to zero out its impact on the environment.”

But the real reason green guilt has no place in Hollywood goes beyond stroking celebrity egos; it’s about nourishing the bottom line. With the green ad market valued at as much as $3.5 billion this year and the green products market being hyped at $200 billion, nobody wants to alienate what Eileen O’Neill, president of the Discovery Channel’s soon-to-be-launched Planet Green channel, calls the “bright green psychographic”—consumers who are receptive to environmental messages and awaiting further instructions on how to achieve an earth-friendly lifestyle. The key to winning over these would-be Begleys, O’Neill explained at Hollywood Goes Green, is to coddle consumers as gently as their celebrity role models. “There’s a lot of overwhelming things about the messages around greenness,” said O’Neill. A slide summed up her channel’s approach to soothing skittish viewers: “Planet Green activates the armchair environmentalist and validates every green choice they make.”

O’Neill’s pitch for “the ultimate green media destination” revealed the focus-grouped, advertiser-friendly heart of Hollywood environmentalism. Planet Green, she said, would strive to be passionate, inspiring, optimistic, and entertaining. Another slide listed what it would decidedly not be: purist, doom and gloom, instructive or didactic, preachy, earnest, or political. Instead, Planet Green’s call to action is based on “conscious consumerism,” explained O’Neill. The traditional environmentalist message that we have too much stuff will be recycled into the message that we simply have the wrong stuff. We will shop our way back from the brink of global destruction one compact fluorescent bulb at a time.

But the Planet Green approach has a point. If you’re trying to fill a cable channel with 24/7 entertainment with an environmental message, a hard sell won’t do. After all, An Inconvenient Truth may have been a fluke—the odd green movie that shifted the debate due to a combination of good timing, savvy marketing, friends in high places, and star power. In fact, not even a big name on the marquee can guarantee the success of a sincere, weighty environmental film: The 11th Hour, a compelling documentary produced and narrated by Leonardo DiCaprio, quietly faded away after its opening last August. Understandably, studios would rather plug green themes into tried-and-true formats such as comedies, home improvement shows, and reality TV. Which is why Planet Green has tapped DiCaprio to produce The Greensburg Project, a 13-part series that follows the sustainable rebuilding of a Kansas town devastated by a tornado.

This repackaging of environmentalism as a nonthreatening mainstream product unwittingly echoes Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger’s recent book Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility, which provocatively urged the environmental movement to ditch its negative, complaint-based approach for a more uplifting, market-friendly one. Exhibit A was An Inconvenient Truth, which, according to public-opinion research done in the midst of the film’s media blitz, did “virtually nothing” to make Americans put global warming higher on their list of concerns. That might have been different, wrote Nordhaus and Shellenberger, if only Gore had “dedicated the last half of his slide show to describing an inspiring vision of the future…Instead, [he] spoke almost entirely of nightmares.”

If environmentalism is truly in need of a makeover, then who better to do it than an ally with deep pockets and the power to shape public opinion? By untethering environmentalism from its old stereotypes, it’s conceivable that Sami and Lucas’ green wedding on Days of Our Lives or a tricked-out biodiesel Chevy Impala on Pimp My Ride introduced ecofriendly ideas to viewers who might otherwise never be exposed to them or would dismiss them as fringe. That doesn’t mean that consumer-driven environmentalism is a solution, but rather one end of an expanding environmentalist spectrum—the “light green” to the environmental establishment’s “dark green.” As the Break Through guys emphasize, optimism is empty without thinking big and focusing on large-scale, long-term efforts to stem climate change and overhaul our economy.

And occasionally, just occasionally, made-for-TV environmentalism may help chart this middle way between superficiality and self-righteousness. Take Al Gore’s amusing cameo on 30 Rock during nbc‘s “Green Week” last November, in which smarmy network exec Alec Baldwin tries to convince him to “throw on a pair of green tights and a cape and tell kids how big business is good for the environment.” After Gore demurs, a smiley-faced Earth prop bursts into flames. “This earth is ruined,” deadpans Tina Fey. “We gotta get a new one.”