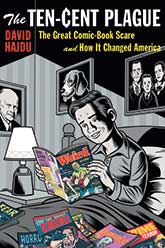

In this earnestly diligent cultural history, David Hajdu chronicles the hysteria that once surrounded the lowly comic book. In the early 1950s, superheroes shared the magazine racks with underdog horror, crime, and romance comics. Titles like It Rhymes With Lust and Crime Does Not Pay depicted a sleazy, yet moralistic, universe where teens mashed at sex parties, the girl next door murdered her abusive father, and many a glowering mug or moll thrust a red-hot poker into the eyeballs of many a deserving snitch. Ultraviolent and anti-social, they were the video games of the McCarthy era. The nation’s bluenoses rushed to protect wayward youths by burning their comic books—sometimes literally.

Hajdu ably details the pyrotechnics of this culture clash, interviewing dozens of the cartoonists and writers who found themselves accused of what psychoanalyst Fredric Wertham had called “the seduction of the innocent.” The climax came with televised Senate hearings in 1954, where Bill Gaines, the publisher of—ahem—Educational Comics (and Mad magazine), was confronted with the cover of EC’s Crime SuspenStories featuring a man standing above a supine woman, gripping a blood-splattered ax and her severed head. “Do you think that is in good taste?” demanded Democratic presidential hopeful Estes Kefauver. Gaines, strung out from an all-night amphetamine binge, stammered, “Yes, sir, I do.”

After that, a draconian Comics Code essentially banned everything but bunny wabbits and Goody Two-shoes in tights. More than 800 comic-book creators were put out of work. For Hajdu, these urban, ethnic, working-class “cultural insurgents” were the great comic-book witch hunt’s forgotten victims. Then, of course, there were the kids, who had to wait a decade for the underground comics that recaptured the anarchism of their ’50s forebears.