Illustration: Maurice Vellekoop

when Henry David Thoreau retreated to the woods, he famously told his readers that he wanted “to front only the essential facts of life.” What he didn’t say is that he also wanted to front the essential facts of his ambition. It was at Walden Pond where Thoreau, an original slacker, finally became a writer. He finished his account of a canoe ride with his brother, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, and wrote the first draft of Walden, the book that made his name.

After 150 years, Walden endures as a monument to frugality, solitude, and sophomore-year backpacking trips. Yet it’s Thoreau’s ulterior motive that has the most influence today. He was one of the first to use lifestyle experimentation as a means to becoming a published author. Going to live by the pond was a philosophical decision, but it was also something of a gimmick. And if you want to land a book deal, you gotta have a gimmick. Recently, with “green living” having grown into a thriving and profitable trend, the sons and daughters of Thoreau are thick on the ground. Not many retreat to the woods anymore, but there are infinite ways to circumscribe your life: eat only at McDonald’s, live biblically, live virtually, spend nothing. Is it still possible to “live deliberately”? What wisdom do we take away from our postmodern cabins?

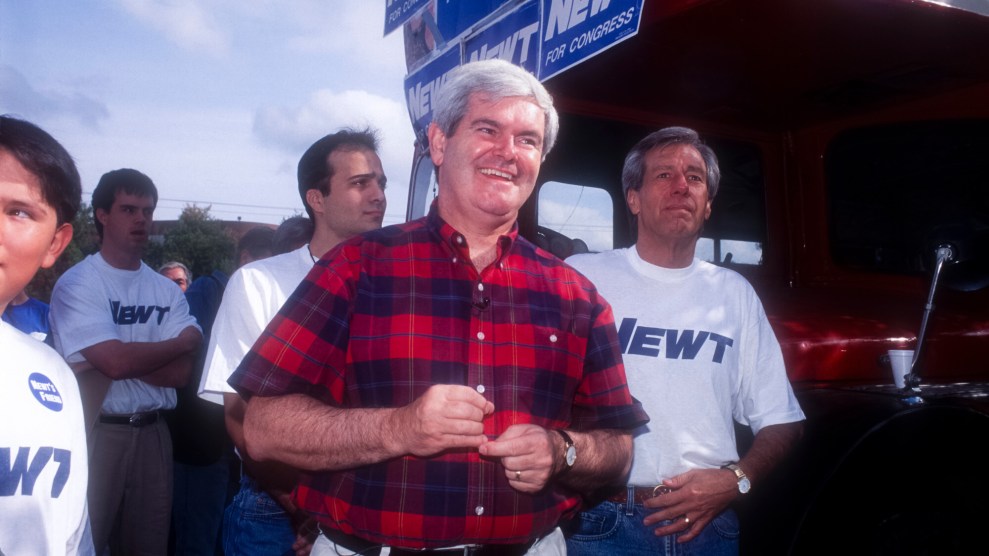

The most notorious neo-Thoreauvian might be Colin Beavan, a 45-year-old New Yorker better known as No Impact Man, and even better known as The Man Who Doesn’t Let His Wife Use Toilet Paper. That last detail was the highlight of a 2007 New York Times profile of Beavan, which portrayed how he, his wife, and their two-year-old daughter were attempting to live in downtown Manhattan with zero “net impact” on the environment. This goal involves eating only organic food grown within a 250-mile radius, composting inside their small apartment, forgoing paper, carbon-based transportation, dishwashers, TV, and adhering to whatever new austerities Beavan dreams up.

Naturally, Beavan is hoping his no impact experiment has maximum impact. Like Thoreau, who, after all, was living on Emerson’s land, Beavan is well connected. He has a book contract. His wife’s friend has made him the subject of her documentary film, and he has a website, where people praise his boldness and question his motives. One commenter, Naysayer, speaks for the cynical: “Well, you’ve found your ticket to fame and fortune. Just undergo a period of time where you are inconvenienced (but plenty of exceptions) then cash in with book and movie deals, then speaking engagements around the globe.” And then there are those whom Beavan has simply annoyed: “For the next year, I will be your polor [sic] opposite,” writes Full Impact Woman. Unlike his deadly earnest spiritual mentor, though, Beavan views his project with an ironic distance, telling the Times, “Like all writers, I’m a megalomaniac. I’m just trying to put that energy to good use.”

Beavan can be overbearing, but every ascetic choice implies a critique of those who aren’t following the same path: I am giving up my car, therefore you are a selfish, earth-destroying auto addict. Also, extreme conservation—not flushing the toilet, not showering, and the like—can turn people off to conserving at all. Thoreau took it on the chin from Robert Louis Stevenson, who wrote of him, “So many negative superiorities begin to smack a little of the prig.” The critique of Beavan is the same. These men have walled themselves off in a little hothouse of their own ego. They are not living courageously and independently in the real world, nor could they if they tried. Fair points, but what’s the alternative? Every decision to try to live differently starts with a little showmanship.

So the self-deprivation author must tread lightly: Bear witness to my extreme example, but realize that I’m just like you. Judith Levine, who charts her Year Without Shopping in Not Buying It, manages this balance gracefully. She goes on a spree before the pledge begins, and keeps in touch with her imperfection throughout. Yes, there is the thrifty virtue in resisting the latest, expensive fashions, but not buying also means becoming a cultural recluse. “An informed person like me needs to see new art, new films,” Levine writes, longing for all the movies passing her by. She and her partner Paul discover that to subsist on free entertainment is to read dusty library books and endure bad performance art. Levine does experience the joyful liberation from stuff, and she temporarily gets off the hedonic treadmill. Yet she also admits that to not consume anything is to become a burden to friends, to feel old, and to develop an unholy craving for Q-tips.

Inspiration for these books can arrive in ridiculous ways. Mary Carlomagno, the author of Give It Up!: My Year of Learning to Live Better With Less, launched her self-denying quest this way: “While reaching for my black sling backs, an avalanche of designer shoeboxes hit me squarely on the head.” Gotcha. She spends a month each giving up different things: alcohol, elevators, newspapers, multitasking, cursing, cell phones, and coffee. (Coffee is a common enemy in these books, including Walden.) Carlomagno is a less rigorous self-denier than most—the height of her deprivation is to give up dining out for a month. Yet she arrives at the same destination as do her peers: reading more poetry, taking longer walks.

While most of these authors accessorize their quests with some larger purpose, Sara Bongiorni, the author of A Year Without “Made in China”: One Family’s True Life Adventure in the Global Economy, decides to boycott China simply to “see if it can be done.” (See our own experiment in buying American.) Her book is marred by a faint jingoistic tone and a deadening obviousness. Guess what? A lot of the stuff in your house comes from China! (But not Hungry Hungry Hippos, apparently.) Toward the end of her year, Bongiorni debates whether to extend her pledge, but concludes, “A Christmas without Chinese gifts under the tree looms like a date with the executioner.” Never has an attempt at conscientious consumption so missed the point.

In all of these self-deprivation experiments, there comes a moment when self-denial becomes self-defeating. An Internet entrepreneur from San Diego named Dave Bruno has received a lot of back pats for his “100 Thing Challenge,” a goal to limit his possessions to that magic number. It’s a useful thought experiment, but do shoes count as one thing, or should each shoe count as a separate item? The point—how much crap do you really need?—can quickly get lost in the details. Ascetics often become distracted by the rules or take things too far. Consider the fervent subculture of people who try to live plastic-free lives. Another perfectly worthy goal, but then you stumble upon advice like this on the blog PlasticLess.com: “Get a Vasectomy: Children are the target market for pointless plastic stuff. Most temporary forms of birth control involve some plastic packaging.” (Uh, okay.)

I don’t mean to throw cold water on earnest self-improvement. But maybe we should set about such tasks in a way that doesn’t reek of personal branding. Thoreau, after all, left the cabin behind, which earned the respect of Robert Louis Stevenson: “When he had enough of that kind of life, he showed the same simplicity in giving it up as in beginning it. There are some who could have done one, but, vanity forbidding, not the other; and that is perhaps the story of hermits; but Thoreau made no fetish of his own example.” While that doesn’t mean not writing a book, it may mean not letting the rigor of your experiment get in the way of the lessons.

All of these writers have good advice for our economically perilous and environmentally precarious moment. Not many, however, were permanently changed by their yearlong experiments. The authors of Plenty: One Man, One Woman, and a Raucous Year of Eating Locally welcome lemons and beer back into their house. Judith Levine is thrilled to buy new socks and starts to consume again, albeit in a more deliberate way. The ultimate lesson of the new Thoreauvians seems to be that change is rarely drastic. We must strive for continuous, daily, incremental improvement toward whatever social, environmental, and economic goals we deem important. That path won’t land you on Morning Edition, but it might just get you to floss, recycle, grow your own food, sit in the dark, air-dry yourself, take daily walks, and read more poetry. Which puts us back where we started: Walden Pond, 1845.