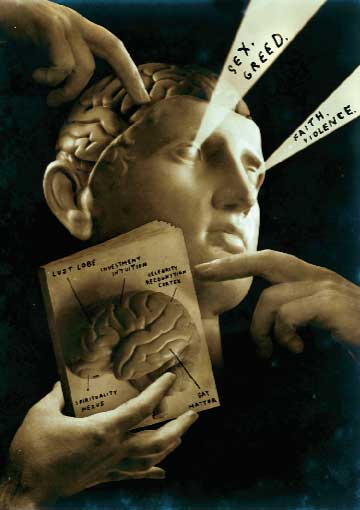

Illustration: Lou Beach

in the lead-up to the election, a popular lawn sign in my neighborhood featured a mock ballot with two choices: Hope and Fear. The red check mark next to Hope was more than just an endorsement of Barack Obama and a potshot at John McCain. It also encapsulated the dual, dueling political worldviews of the ’08 race. For liberals, it was a battle between the selfish appeal of the status quo and an altruistic call for change. For conservatives, it was about protecting ourselves from shallow feel-goodism.

Such contradictory story lines emerge in all elections. But in this past cycle they had something in common: Both flattered each side’s belief that it was the only truly virtuous one, the only one capable of ensuring the public good. In his campaign’s “closing argument,” Obama appealed to our “better angels” instead of our “worst instincts.” Meanwhile, Bill O’Reilly told viewers, “Don’t vote emotion; vote for the good of the country.” McCain urged us to put “country first.”

Yet are we really capable of transcending our self-interest for the benefit of the many? J.D. Trout’s The Empathy Gap and Dacher Keltner’s Born to Be Good weigh in on the age-old question of whether we are inherently selfless or selfish—and how these hardwired impulses might best be harnessed to create a more perfect union. Their timing could not be better: In the still-churning wake of George W. Bush’s disastrous presidency and the collapse of the conservative movement, the issue of what really drives our political choices has never seemed more urgent—or confusing. Can a high-minded leader like Obama really kill off “politics as usual”? Or are we doomed to talk a good game about altruism even though we’re programmed to act like jerks every time a politician pushes our partisan buttons?

Judging by the title of his book, you’d think that Trout, a philosophy professor at Loyola University Chicago, thinks we can see beyond ourselves. He kicks off with St. Thomas Aquinas’ tender definition of empathy (“the heartfelt sympathy for another’s distress, impelling us to succor him if we can”), then swiftly kicks it to the curb. Yes, we may have “Dalai Lama neurons” that fire when we see other people suffering, but Trout has plenty of psychological and physiological evidence that we’re not predisposed to be saints. Thanks to unconscious brain glitches like the “fundamental attribution error,” we’re inclined to blame other people for their problems, but chalk up our own misfortune to bad luck or circumstance. One neurological study found that images of starving children stimulate the amygdala, the part of the brain that reacts to threats, which might actually shut down compassion. We’re more likely to donate to charity based on our own state of mind (hungry, depressed, etc.) than in response to the actual need of others. The egocentrism of empathy can lead to good—for instance, when politicians champion causes that have touched them personally. But when it comes to something like tackling poverty, our leaders are too well fed to be of much use.

But while Trout is skeptical of altruism, he refutes the Enlightenment idea that we can compensate by employing reason. Deep down, he convincingly (and depressingly) argues, we’re nothing but bundles of built-in biases. We succumb to “base-rate neglect” and fall for sensational stories about school shootings even though they’re statistically rare. “Overconfidence bias” makes us underestimate the challenges we face, even if it’s something as simple as figuring out how long it will take to pack to move. (No wonder we’re dallying on climate change.) And thanks to the pernicious “anchoring bias,” information we know to be meaningless or false lodges—or anchors—in our heads despite our best intentions to ignore it. This is why negative campaigning works: Bill Ayers-type attacks only have to plant the seeds of doubt; the compost of our minds does the rest.

To compensate for our hopelessly selfish, clouded brains, Trout offers “prosthetics for our stunted judgment” in the form of, well, would-be philosopher kings like himself. He proposes that a slightly creepy-sounding House Committee on Social Science vet legislation and weed out policies that don’t pass muster. He doesn’t say much about how such a body would convince us to accept policies that go against our instincts, but gives plenty of examples of how “outside strategies” can be used to trick people into doing the right thing. The Amsterdam airport, for example, cleaned up its men’s rooms by sticking decals of a fly inside its urinals. Men unconsciously aimed for the fly, and voilà—”urine spillage” dropped 80 percent. If we can fool guys into peeing straight, then maybe we really can clean up Washington.

Where Trout sees flaws in our nature, Dacher Keltner sees perfection. A professor of psychology at the University of California-Berkeley, he maintains that we’re all good guys at heart. The villain is our “broader ideology about human nature,” particularly the assumption, perpetuated by Machiavelli, Ayn Rand, and the gop, that we are “selfish, competitive gratification machines.” Instead, he insists, our emotions are not “disruptive, base tendencies”—they are “commitment devices…embodied in our bodies, [that] shape judgment in [a] systematic fashion.” In other words, we don’t need religion or government to make us follow the Golden Rule; it’s already in our brains. We are not “wired to prioritize the bad.”

Unfortunately, however, modern life has made us lose touch with our basic nature. Keltner cites an experiment where subjects were asked to interpret another person’s facial expressions. When they saw someone making sympathetic faces, the subjects mistakenly thought she was constipated or drunk. Even the human voice turns out to be a poor communicator of our pro-social emotions. It seems that only touch can foster true compassion. Which is why Keltner, like Bowling Alone author Robert Putnam, wants us out in the world, playing pickup basketball, finding awe in nature, and—if we’re as lucky as he is—getting our earlobes playfully squeezed by the Dalai Lama.

Keltner suggests we all strive for the Confucian concept of jen, in which a person “brings the good things of others to completion and does not bring the bad things of others to completion.” But when it comes to politics, he avoids coming off like Dennis Kucinich in a lab coat. He doesn’t have techno-utopian dreams like Trout; he makes no grandiose calls for a Department of Peace or an inspector jen-eral. We can never eliminate the bad, but we can overcome it with individual good.

Can this optimistic, grassroots proposal for stimulating human kindness be reconciled with Trout’s wary, top-down approach? When it comes to the nitty-gritty of governing, is there a third way between aimless selflessness and narrow selfishness? Perhaps. One of Trout’s more populist suggestions is to create “minipublics,” small panels of randomly selected “ordinary folks” that would weigh in on policies before they’re implemented. As an antidote to blue-ribbon panels, similar efforts have been attempted in Canada, where they have tackled tough issues such as election reform. Trout thinks minipublics would help us keep our biases and shortsightedness in check. Yet they also could be a way to give us the intimate social experiences that Keltner believes will restore our capacity for empathy.

It may sound like the public-policy equivalent of jury duty, but this kind of civic obligation might satisfy Americans’ hunger to do more than just mark a ballot every four years. We want to do right, but we’re also inclined to think that our righteousness is not based on our actions, but rather the despicableness of our opponents. In his acceptance speech, President-elect Obama seemed to acknowledge this when he called for hard work and sacrifice in the years ahead. His success or failure may hinge on whether he can convince enough of us that doing good doesn’t always feel good.