Bruce Jackson

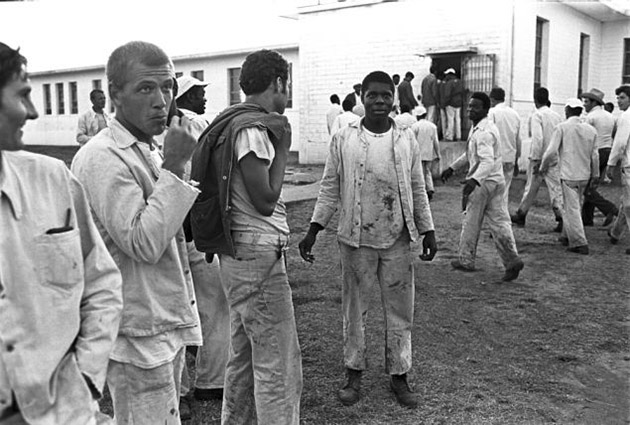

In the summer of 1964, Bruce Jackson—then a junior fellow at Harvard—arrived in Texas to record work songs on several state prison farms. He was researching the music and folk culture of incarcerated men, a project that had earlier steered him to Indiana State Prison and Missouri Penitentiary. Landing in Texas was essentially dumb luck; Jackson had family there, and knew that the Lone Star State claimed many of the country’s harshest prison farms.

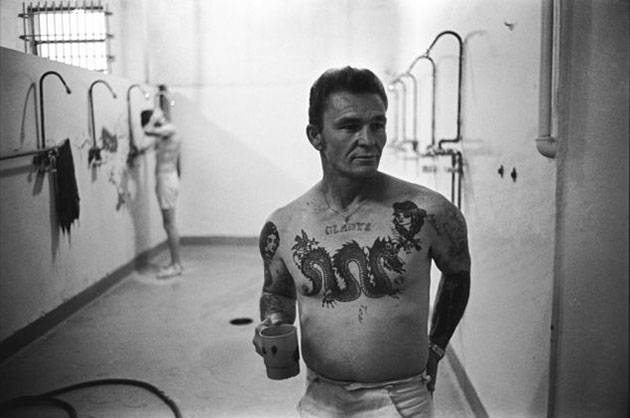

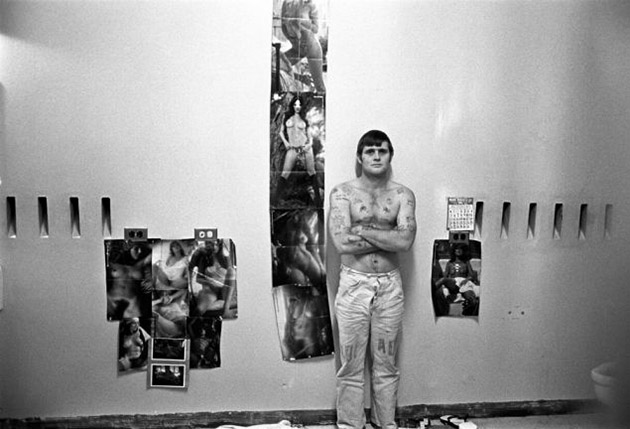

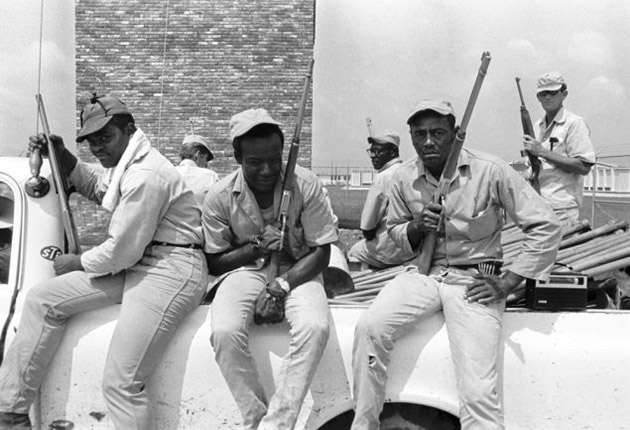

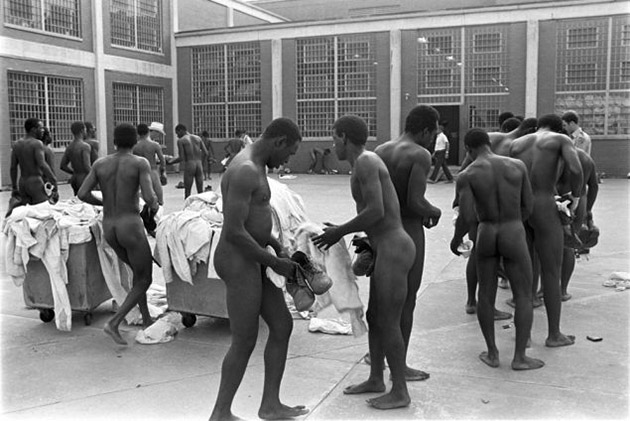

Besides audio equipment, he also brought a 35mm Nikon with which he intended to create a visual diary of the inmates he met. Fifteen years and thousands of photos later, the diary had become more like an encyclopedia—portions of which you can now read.

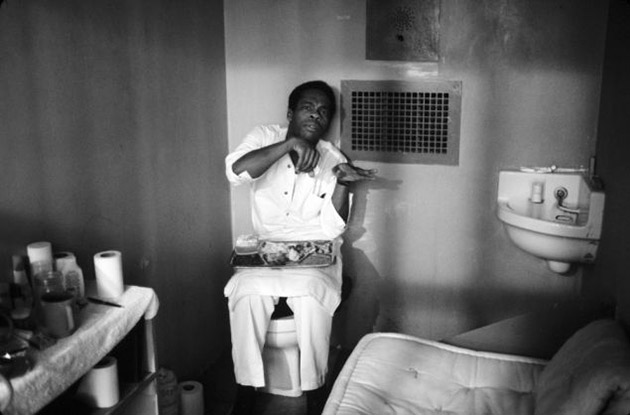

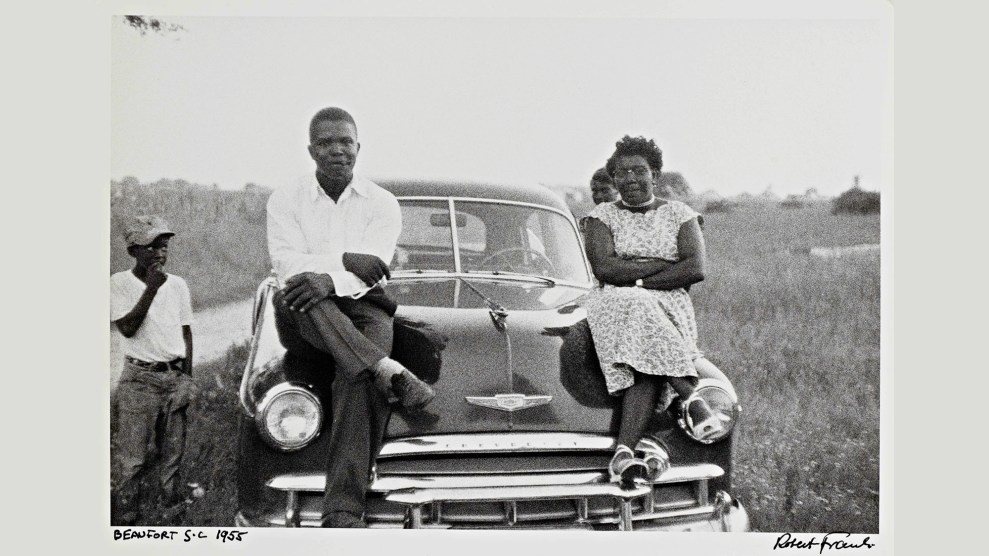

In his new book, Inside the Wire: Photographs From Texas and Arkansas Prisons, Jackson documents a society and economy whose roots were entwined with the antebellum South. Many prison farms were converted slave plantations that still bore the family name of long-buried landowners: Ellis, Ramsey, Cummins, Wynne. Sprawling across thousands of acres, these were agricultural purgatories where prisoners harvested much of their own food, spun cotton into clothes, and staged annual rodeos for the amusement of each other and the locals, all while living under the long shadow of death row. (The state prison system’s psychiatric unit, Jester IV, is located on the site of a former prison farm called Harlem Plantation, but that’s another story.)

Like Danny Lyon, whose seminal Conversations with the Dead was shot in many of the same prisons where Jackson worked—the director of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice sought Jackson’s approval before granting Lyon access—there’s no doubt where the photographer’s sympathy lies. Although many of the men pictured were convicted of brutal crimes, Jackson imbues them with dignity, or at least a degree of stoicism. And just to dispel uncertainty about his own politics, Jackson writes: The prisons “continue to be grim places where American society hides its failures…the two primary functions shared by American prisons now are providing jobs to people in rural counties who would not otherwise have jobs, and keeping off city streets people the cities don’t know what else to do with, about, or for, or just don’t want to look at.”

Prison farms have grown increasingly marginal. In 2005, the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that only 298 facilities still employed inmates in agricultural labor, a 12 percent drop from 1990. The nation’s remaining farms, such as Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, feel anachronistic, or like relics of a system that reduced convicts to sheer manpower. Although prison bureaucracy has modernized, the core reality of life behind bars remains grimly constant. As Jackson notes: “I doubt the world has changed much in the interim, other than that it is even more crowded and more mean.”

These images are excerpted from Inside the Wire: Photographs From Texas and Arkansas Prisons, published by University of Texas Press.