Update (9.3.13): Another dubious development in Larry Ellison’s troubled quest to mainstream the America’s Cup: The Cup jury penalized Larry Ellison’s Team Oracle USA after the team was accused of deliberately violating race rules during the preliminary races that precede the official America’s Cup races. Four members of Team Oracle were banned from participating in part or all of the Cup—the first time sailors have ever been banned for what the San Francisco Business Times called “cheating.” Team Oracle has been docked points and fined $250,000 that will go to charity. Now, in order to retain the Cup, Ellison’s team will have to win 11 of the 17 races in the series, which starts on Saturday, September 7.

The scandal first came to light in early August, when the America’s Cup was gearing up for youth teams to race the AC45 catamarans Team Oracle and competitors had raced in the preliminary series. Regulators found that Oracle’s boats were heavier than allowed by the racing rules, which gave the team a competitive edge in the races; they found bags full of resin or lead in two boats inside a part known as the king post, according to the jury’s report, which you can read here (PDF).

*****

“…and the crowd goes wild!!!” an announcer enthuses over the loudspeakers at an America’s Cup viewing area on the San Francisco waterfront. The crowd, realizing that this is the point where it is supposed to be going wild, lets out some perfunctory cheers. Some onlookers take an anticipatory gulp of a beer, which is selling for $8 to $12 a pop. The New Zealand boat rounds the final mark and crosses the finish line minutes in front of its competitor, owned by Prada CEO Patrizio Bertelli, and swings down by the waterfront so fans can catch a better look.

Up close, the boat is an immaculate carbon-fiber spectacle, a marvel of engineering. Even while doing its victory lap past the spectators, it’s impossibly fast. The waving crew is tiny compared to the “Fly Emirates” ad prominently displayed on the boat’s 130-foot-tall sail—since each team spent around $8 million to build its boat, it’s financially necessary to deck them out like NASCAR racers. The sailors wear body armor and carry ropes, knives, a water-activated strobe light, and small bottles of air good for a few breaths in case a boat capsizes and they are trapped underneath.

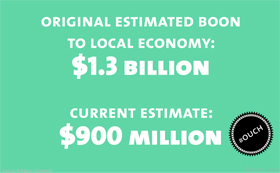

Such was the scene at a trial run for the America’s Cup, the international sailing event that San Francisco never asked for, and by which its habitants have alternately been thrilled, horrified, and baffled since the hoopla began in early July. The Cup was brought to San Francisco by the billionaire tech prince Larry Ellison, who managed to sell City Hall on the notion that it would bring glory, and more than $1 billion in economic activity, to the Bay Area. (Click the box at right to see the numbers.)

But ever since Ellison and the city cut their deal in late 2010, the Cup has been plagued by skepticism over what San Francisco would actually gain as its host. At one point, it appeared that city taxpayers would have to shell out as much as $32 million, although San Francisco would reclaim some of that through higher tax revenues. Current cost estimates are significantly lower because the event will be smaller than projected: Only 4 boats ended up in the competition, not the 10 to 15 organizers had expected. That meant significantly smaller crowds, thus less police overtime and so forth—the city, its rep on the line alongside Ellison’s, has attempted to spin this as good news. Read on for the lowdown on the cash and the characters and the inevitable lawsuits and political skirmishes that make the America’s Cup sailing’s biggest circus act.

Welcome to the Larry Ellison Cup

As the 2010 winner, Larry Ellison got to choose the location of the next race. Ellison, an avid sailor who currently holds the Cup—like the Stanley Cup, it is a physical trophy—is the swashbuckling cofounder of Oracle, the Bay Area database-software maker. According to Forbes, Ellison is the world’s fifth-richest man, not to mention the owner of 98 percent of the Hawaiian island Lanai. He once offered his neighbors $15 million for their $7 million San Francisco home because their redwood trees were blocking his views, and then took them to court when they refused the offer.

Historically, the Cup is a rarified event that takes place far from shore. Ellison dreams of turning it into a spectator sport the public can watch from land and view live on network television. That’s a tall order. “San Francisco is a notoriously prickly place to hold an event like this,” says Julian Guthrie, who wrote a book about Ellison’s crusade to bring the Cup to San Francisco. Consider the struggles of basketball’s Golden State Warriors, who have been working for years to move from Oakland to a waterfront stadium in the city. “This is a NIMBY town,” Guthrie explains.

Ellison no doubt knew this, but he’s not the type to give in easily. Indeed, look around these days, and you’ll see the America’s Cup and Ellison on display all around the city. Witness…

The massive event space: The city of San Francisco spent $22 million to help Ellison develop two San Francisco piers and a waterfront park, the Marina Green, as public viewing areas. Since much of the racing happens out of sight, the piers are equipped with giant screens—there are also exhibits, concessions, and other trappings you might find at any stadium. You can reserve semi-private tables in a “VIP section” above the public area for $35,000 for the three days of Cup finals. Private waterfront “chalets” will run you $400,000. If you’re looking to tie up your yacht, you’ll pay anywhere from $36,000 to $160,000 for a three-week mooring. Ellison’s Event Authority (the group running the event) gets to keep all the revenue from all of these rentals.

The 9,000 seat concert venue: Sting, Sammy Hagar, and the Jonas Brothers were among the host of acts booked at an outdoor venue Ellison’s people built on land supplied by the city. Next Wednesday, for instance, you can catch Heart with Jason Bonham’s Led Zeppelin Experience (tickets: $26-$100.50). The concerts are promoted by LiveNation, which leases the venue from Ellison. Under normal circumstances, the city would demand a cut of the revenue from other concerts on city-owned property. In this case, San Francisco won’t see a dime in ticket revenue.

Exhibits at two major art museums: The Asian Art Museum is exhibiting Larry Ellison’s Japanese art collection, which the San Francisco Chronicle called one of the museum’s “finest exhibition projects”—possibly because Ellison hired the museum’s former art director to build his collection. The America’s Cup trophy—definitely not art and definitely not Asian—was on display during the opening days of the exhibit.

San Francisco’s natural history museum, the California Academy of Sciences, is hosting a “Built for Speed” exhibit sponsored by Oracle and by Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt and his wife. Museum-goers get to learn about fast things like fish and orcas, and can “examine” up close a boat similar to Team Oracle’s.

A documentary, produced by Ellison’s son and narrated by Jeremy Irons: Ellison commissioned his son David, a film producer, to make a movie titled The Wind Gods telling the story of his father’s victory in the 2010 Cup. The film, which later aired on PBS, screened at the America’s Cup event space last spring. Guests received books about Ellison’s America’s Cup career in their goodie bags.

The 16-hour NBC America’s Cup infomercial: The idea to make the America’s Cup into a grand, televised event was at the heart of Ellison’s plan for a reinvented America’s Cup. If Ellison succeeds both in winning the Cup and selling it to the public as a spectacle, then the TV deal could prove lucrative for him down the road. To make sure it succeeds, Ellison has employed helicopters with military-grade GPS and wired the boats with sophisticated tracking systems and more than a dozen microphones to make the broadcast more thrilling.

The equipment is rumored to have cost a fortune, and so will all that air time: NBC isn’t buying the rights to the America’s Cup. Rather, Ellison’s Event Authority purchased air time from the network. Yep, Ellison is paying NBC, not unlike an infomercial, to air 16 hours of national regatta coverage this month and next.

How did Ellison snag the cup to Begin With?

Ellison’s 2010 victory in Valencia, Spain, was years (and millions of dollars) in the making. From 2007 to 2009, Ellison fought a series of legal battles so that his team could replace a newly formed Spanish team that was set to compete. He won, then proceeded to fight then-Cupholder Swiss pharmaceutical heir Ernesto Bertarelli in New York state courts over the time and location of the race. Ellison’s lawyer was David Boies, who represented Al Gore in the 2000 recount battle, and George Steinbrenner in his suit against Major League Baseball.

Eventually, the terms of the race were settled and everything was set to proceed until, just days before the race, Ellison replaced the soft sail of his boat with a stiff carbon-fiber wing. Bertarelli’s boat couldn’t compete with the new design, and Ellison prevailed.

To the casual observer, all these lawsuits, dangerous boats—a sailor was killed after a team’s AC72 capsized earlier this year—and obsessive one-upmanship might make it seem like Ellison is trying to destroy a 160-year-old regatta. But such power plays are as much a part of the event as the actual sailing, according to America’s Cup historian Chris Pastore. “Yacht racing is inherently litigious,” he says.

This is hardly the first time people have fretted about the race being too dangerous. In 1903, Cornelious Vanderbilt and William Rockefeller spent about $4.6 million in today’s dollars to build the Reliance, a marvel of engineering in its day—just like the AC72 is in ours—in order to best their rival, Sir Thomas Lipton. They employed engineering tricks that let their boat be bigger than Lipton’s while still meeting the technical specifications for the race.

Half a million people gathered to watch Lipton’s defeat off the coast of Sandy Hook, New Jersey. After the race, both parties agreed to ban boats like the Reliance from future America’s Cup regattas because the boat, it was said, was too dangerous to sail.

will the Cup be a win for San Francisco?

If a billionaire wants to build a $8 million boat, race it against his wealthy friends, and commission his son to make a documentary about it, that’s all fine and good. But even someone as wealthy as Ellison needs to enter into a relationship with the host city to put on an event of this size.

Early on, San Francisco intended to give Ellison rights—valued at $90 million—to land and piers on the waterfront; a 66-year lease agreement would allow him to improve the run-down properties and run things as he pleased. The plans were even more ambitious then: Bleachers on Alcatraz Island, a heli-pad barge, and a floating 44-foot video screen (a particularly contentious element) were all in the works.

Opponents, ranging from community groups to the Sierra Club, began filing complaints—and eventually a lawsuit that settled out of court. In a plan they dubbed “Occupy the Bay,” a Bay Area swimming club threatened to swim into the paths of yachts and spectator boats during the races if the Jumbotron were built. Over time, organizers’ ambitions were pared down, and Ellison’s lease agreement was dialed back to something far more modest. Former SF Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who led the lawsuit, thinks the city was daft when it first started playing ball with Ellison. “You didn’t need to do a lot of research to realize that no matter how many times Gavin Newsom said it, it’s not the Olympics, it’s not the Super Bowl, and it’s not the Olympics and the Super Bowl combined,” he says.

As Cup preparations were underway, it became clearer that the race wasn’t going to yield all of the glittering benefits Ellison initially promised: An economic downturn in Europe, combined with the extreme price of entry and San Francisco’s nonidentity as a yachting destination all conspired against the Cup. The city now expects around 2 million spectators, down from 2.7 million, and only four boats, not a dozen or more. Louis Vuitton, one of the key sponsors, was so disappointed by the turnout of competitors that it asked for and received a $3 million refund.

There were labor troubles as well. Last spring, the city ordered Ellison’s Event Authority to pay $460,000 in back wages to workers who had built bleachers by the waterfront because the organization had failed to pay the prevailing wage—basically wages plus benefits—as it had agreed to do.

Supervisor John Avalos, who held a city hearing about the back wages, expressed disappointment over what the Cup wasn’t bringing to San Francisco: Originally, there had been talk of neighborhood art, increased tourism across the city, and other general benefits. “We were promised so many things,” Avalos told Mother Jones. “We’ve really seen nothing if you’re not directly in the port industry or the racing industry.”

David Chiu, president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, insists that the Cup will bring broader benefits and that San Franciscans shouldn’t be too quick to write it off. “When you put close to $900 million into the local economy, that has multiplier impacts throughout the entire city,” he says.

Will taxpayers have to pick up the tab?

Fundraising to cover city expenses also has fallen short of expectations. At first, local developer and politico Mark Buell, who ran the organizing committee for the event, was tasked with raising $32 million to defray the city’s costs. But Buell and the committee were under no actual obligation—they promised to “endeavor” to raise the money. As of January, Buell had only secured $9 million, so Mayor Ed Lee wound up taking on the task himself. If Lee fails to raise enough through donations and Cup-related tax revenues fall short, the city may be adding millions to its $100 million deficit.

But city taxpayers won’t have to shell out as much as some critics feared, thanks to the lower projected attendance. Also, developers who are eager to build on the city’s waterfront have begun ponying up. In June alone, a real estate developer battling to build luxury condos donated $10,000; the Golden State Warriors, who are vying for that waterfront stadium (and have been accused of trying to cut corners) gave $25,000; and developer Thomas Coates contributed $100,000. The new fundraising total is around $16 million, only half the original goal, but just $6 million short of the city’s break-even point.

So What’s a San Franciscan to do?

It’s hard to say who will have the last laugh. The America’s Cup could be a bust, giving some satisfaction to the naysayers who have been waiting three years to gloat: “I told you so.” Or it could scrape by, thanks to the reduced scope of the event and the down-to-the-wire push to raise funds. But if it does okay, and if Ellison wins the race and decides to host it here again, it could help make San Francisco a sailing destination.

In the meantime, here’s the race schedule, so you can buy yourself an $8 Bud Light and enjoy the spoils of the city’s latest culture war. Maybe you’ll even catch a glimpse of Ellison’s Danish-designed Musashi megayacht, which is a touch longer than a city block and has a glass elevator to shuttle passengers between its three decks.

If you’re going to root for a team, consider Team New Zealand, the only boat without a billionaire behind it. If New Zealand wins, team leader Greg Dalton has said he’d like to pare down the hype and get rid of the “sailing billboards,” as he calls the new high-tech sails.