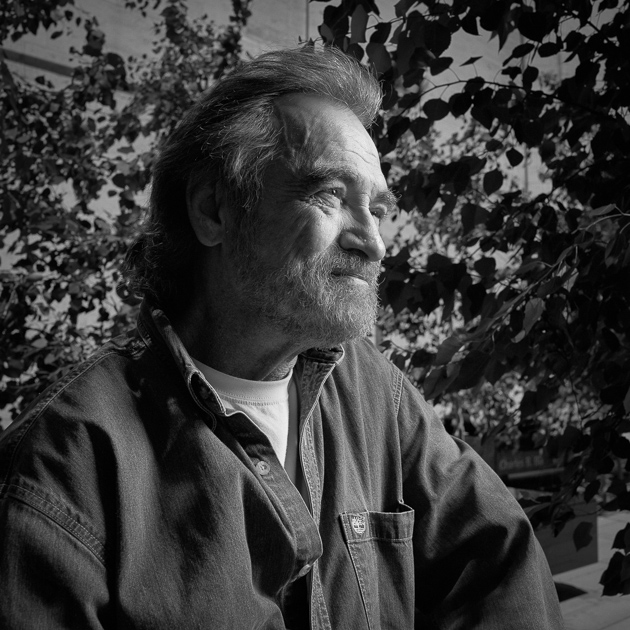

Over more than five decades, Donnie Fritts’ behind-the-scenes contributions—as a songwriter, session musician, and bandmate—have become integrated into the very DNA of soul and country music. Born and raised in Florence, Alabama, Fritts, 72, contributed to the birth of the famed Muscle Shoals recording scene as a regular presence at Tom Stafford’s studio and as a close friend of Arthur Alexander, a black singer whose early songs were covered by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. When they weren’t recording, Fritts and other Muscle Shoals studio musicians would make money playing R&B on the local fraternity circuit. After moving to Nashville he befriended a young Kris Kristofferson and joined his band, where he remained for several decades. Among his many writing credits, Fritts’ ballad “We Had It All” (co-written with Troy Seals) is an undisputed country-soul classic, recorded by everyone from Ray Charles to the Stones.

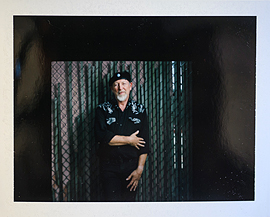

Fritts averages one solo album per decade going back to 1974’s Prone To Lean. Out October 9, his fourth and latest record, Oh My Goodness, gives listeners the best opportunity yet to appreciate Fritts’ rough yet vulnerable voice, love of song, and earthy funkiness. Musical support comes from the likes of Single Lock Records co-founders John Paul White and Ben Tanner, along with Brittany Howard, Jason Isbell, and John Prine—all of whom stepped back to allow Fritts to fully shine, a testament to lessons learned from the deep but unassuming musician. I interviewed and photographed Fritts this past summer in New York City.

Mother Jones: John Paul White tells this story of when he first met you: You were at a keyboard at home playing Amanda McBroom’s “Errol Flynn” and tearing up as you sang it. Singing must be a very emotional experience for you.

Donnie Fritts: Extremely! There are some songs that I know if I tried to sing right now I couldn’t do it. That damn “Errol Flynn” gets me every time.

MJ: It’s a beautiful song, with a pretty complicated premise and structure.

DF: It really is. I haven’t talked to the gal that wrote it, but she sent me a letter through the label and was very sweet. She loved how we did it, because it’s nothing like the way she wrote it. Which is cool. She did it the way she did it. Her version is more operatic. She wrote “The Rose,” which Bette Midler recorded. It was a huuuuge hit. I’d like to hear the demos she did on that damn song. This girl can write.

MJ: You were close with Tom Stafford during the onset of the Muscle Shoals scene. What was he like?

DF: He was an odd character, you know—a brilliant guy. He looked weird and I think he took a really defensive attitude about being a hunchback. You know how people can be, giving him a hard time. So he turned that into a defensive mechanism. He would strike first, a lot of times. But he was a great guy, and really those talks we had when I was about 15, out of all of that came the studio over the drugstore and everything else. I’m not saying—I’m no big deal, but I was a part of the birth of the music there.

MJ: I gather people were always hanging out and talking with him at that first studio. What were those conversations like?

DF: Something about everything. You got to understand, Arthur Alexander was there with us, and some of his crew. It was in the ’50s in Alabama. It was before even the civil rights stuff even started. You can imagine the hatred, although we didn’t have it as bad as other parts of the country, I must say. Nobody acted on it as bad as some places like Birmingham, but it was a concern. The only thing we could do was joke about it.

MJ: Alexander is another very special figure.

DF: I loved that guy so much. We were like brothers just right off the bat. He was a very deep thinker. You know how Jerry Lee Lewis always had this fight going on in his soul—Jerry Lee was doing all of this shit wrong, singing for the devil or whatever? Then he’d get on the other side and be singing all this gospel. So it was a continual good vs. bad cycle. Arthur had that going.

We wrote a song called “Thank God He Came.” It was on that Warner Brothers album that has “Rainbow Road” on it. Anyway, he kept having a hard time with fact that it was a gospel song. He loved that music and he didn’t want to use it in the wrong way. I said, “If nothing else, that song can help people, it can inspire people.” But man, he had trouble with that. He had a lot of bad incidents happen where he would just go off. He caused a big scene at a church one night. But that was a big struggle with him. We’ve talked it out so many times.

MJ: In the song “Tuscaloosa 1962,” you paint a picture of the Muscle Shoals scene and the fraternity gigs. Tell me about that.

DF: The guys that I played with, Hollis Dixon and the Keynotes—just about all the great musicians from Muscle Shoals came through his band at one time or another. Hollis seemed to get the best work. He was really funny on stage and a good singer. We played fraternity parties and kids’ dances. They were called “lead outs” for kids in high school. We played wherever we could—in the down time when you weren’t recording, people had to make money.

I was in Hollis’ band for eight years, playing drums. At one time we had Barry Beckett, Jimmy Johnson, David Hood—everybody but Roger Hawkins. We had a hell of a band. You talk about being the weakest link—here I am playing drums! Spooner Oldham was in it most of the time too; it was rockin’! We did a few recordings: We cut stuff at FAME, but I don’t think anything was really done with it.

MJ: As FAME records started take off, Rick Hall was putting together a stable of songwriters to support the label and the recording studio, but you didn’t sign with him. You worked with Nashville people instead. How come?

DF: The main reason was a lot more money. I didn’t move, I was still there in Muscle Shoals for another 10 years, but I was writing with different people in Nashville—whoever I could. Eddie Hinton came on the scene about 1963, and about four years later we wrote a ton of songs together. I drifted around, but Eddie and I had some cuts through the ’60s and ’70s. I went on the road with Kris Kristofferson in 1970.

MJ: How did that come about?

DF: I was writing for a publishing company in this old building right next to the RCA Victor Studio in Nashville. We were on the top floor, and Combine Music was on the bottom floor. Combine had Kris and Billy Swan and Tony Joe White, so I was friends with all those guys. Finally, Kris was starting to get cuts, and he decided he was going to try to get into that business of touring, because he looked like a star—he just had to do it. So I went with them when they did their first show at the Troubadour in Los Angeles. I was just hanging out. We had a great time. We got to go to Jack Nicholson’s house. First trip to LA and we end up a Jack’s house! He was real sweet.

The next show we did, this guy who owned the Troubadour, his name was Doug Weston, a big tall son of a bitch. Strange, but a good businessman. He opened up a brand new Troubadour in San Francisco, and we were the first act to play there. That’s when I joined Kris’ band, on his second show ever.

That was June of 1970. Things moved pretty fast. Every big city had a club like the Troubadour, and we played every one of them. By August, we got booked on the Isle of Wight festival. That was huge, a big damn deal. By Christmas, we were at Carnegie Hall. We were a bunch of guys who didn’t have any idea what we were doing, but we had Kris’ songs. As long as you have those brilliant songs, it didn’t matter how bad you played, or how bad he sang on ’em sometimes. It was one of those magical things that really worked, and I don’t think could ever happen again.

MJ: In 1974, you released your first solo album. How did that come about?

DF: Well, I was wanting to do an album but I didn’t know if I was really ready. Jerry Wexler was one of my closest friends and allies, like my godfather. He said, “Let’s do an album.” So great, we got Kris to co-produce it. I couldn’t sing worth a damn, but there were some good songs.

MJ: On that album was “You Had It All,” which was covered by an impressive list of people. What’s the story behind that song?

DF: It was total luck on my part. I went to visit a friend of mine, a writer name Troy Seal, a songwriting fool. He’s had a ton of hits. He said, “I’ve got a thing I’m stuck on.” ?I can hear the wind a blowin’—he already had that. You and me lord, we had it all. ?He only had that first verse. For some reason he was stuck. But that’s how that came about.

That song has meant a lot of things to a lot of different people. We got it in front of Ray Charles, that was a big deal for me. The Stones cut it. Bob Dylan cut it—even though Ray Charles means the most to me. Dobie Gray was the first one to cut it, and I would have to say Dobie probably had the best record on it. In terms of a commercial record, nobody’s going to beat Ray singing it. He changed a couple parts to make it work commercially, which is okay by me. He can sing it in Chinese if he wants to!

MJ: Since 1974, you will have only released three solo albums. Are you reluctant to be in the spotlight?

DF: There’s a reason for us getting into the music business, and that’s for performing. If you’re a songwriter, it’s to perform your songs. For singers, it’s just to get to sing somewhere. So while there may be a reluctance with all the things that go along with it, you got to choose, and this is one of my big opportunities to get back doing it.

MJ: Single Lock, your current label in Florence, Alabama, uses some of the original Muscle Shoals musicians for recordings, but develops new artists as well. What are they trying to accomplish?

DF: They are carrying on the tradition in their own way. It can’t be the same as what we did; it’s a totally different world. By they, by God, will get in there and work. Their hearts are in the right place. And for John Paul to give me a shot, I’ll never forget as long as I live.

MJ: What do you hope will come from doing an album now?

DF: Well, your hope would be to at least make a little bit of noise and have a little action on it. Or a lot. I know that’s tough. It’s a roll of the dice, and everything’s against you, really. I’ve been there many times. I’ve known just thousands of people a hell of a lot more talented than me who never could get anywhere. So I don’t know what the answer is, but I’m very blessed and lucky to have made a good living doing what I’ve loved to do. I just hope I can do another one after this.