In the late 19th century, the US government opened the first of 25 off-reservation “American Indian boarding schools.” Over the years, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were bused to the schools as part of a federal effort to inculcate them with Judeo-Christian values and speed their assimilation.

The last of these schools, the Sherman Institute, opened in Riverside, California, in 1903. In a new photo book, Shadows of Sherman Institute, co-authors Cliff Trafzer, tell the story of the school and its students with the help of more than 150 rarely seen images.

“It’s a hidden part of American history,” says Trafzer, a professor of American Indian History at the University of California-Riverside who began working with the school, now Sherman Indian High School, in 1991. “Few people know about the boarding school system and the United States government taking children and bringing them to these schools, separating them from their families and their communities on purpose.”

Many of the photos show students learning practical skills, such as sewing, smithing, or shoemaking. Those that appear staged, Trafzer says, were typically used by administrators to lobby for more federal funding.

“Yes, they were teaching English, a little bit of math and science, but the emphasis was on making it a trade school—to make Native Americans useful,” he says. “To make them part of broader society. It was part of the assimilation program of the United States, to totally change them. That’s what we’re seeing. An attempt to destroy that which was Indian and re-create people in the image of White America.”

Here’s a selection of photos from the 1940s and 1950s taken from the book, which is available in paperback.

Students arrived at Sherman Institute by bus, typically from rural reservations.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

Girls learned to quilt as part of the school’s domestic science curriculum.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

Students were responsible for cooking and food prep. Here, boys make biscuits or rolls. Male students could take a vocational course to become bakers, an option not available to the girls.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

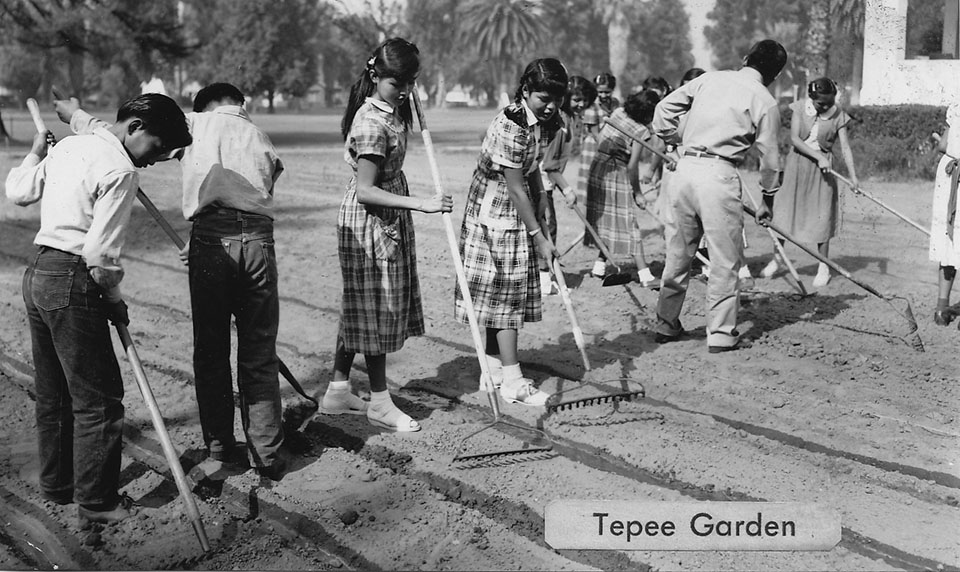

Students work in a dormitory garden. The school gardens were intended to teach self-reliance through Western growing practices. This photo is probably staged, given the relatively formal clothing.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

Short haircuts were mandatory for boys. Students learned to work as barbers (boys) or hairdressers (girls).

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

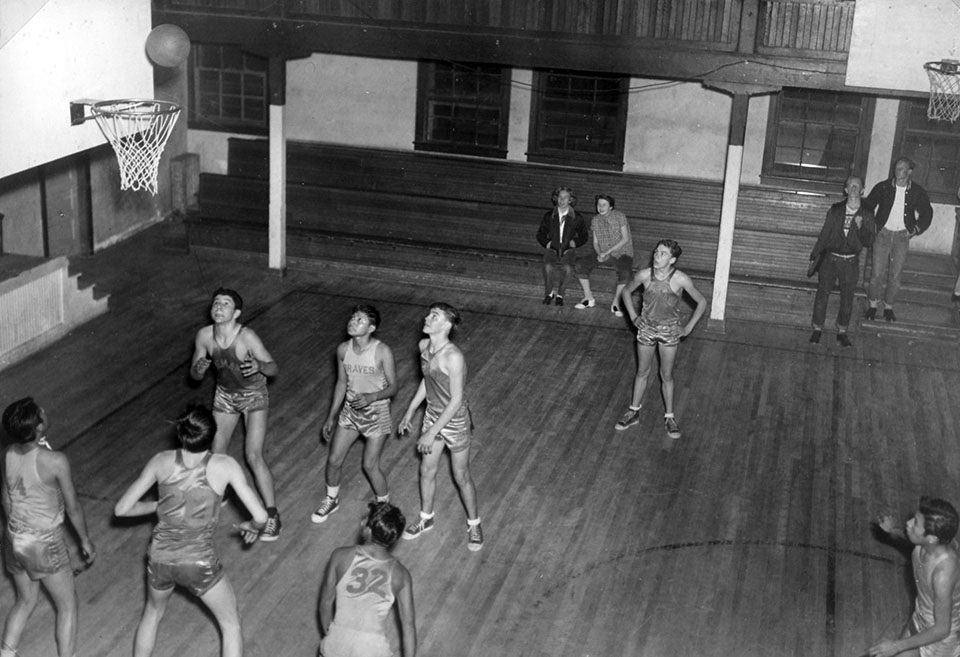

Sherman boasted a sizable gym, and boys’ and girls’ teams hosted other schools for basketball competitions. The sport was relatively popular on Indian reservations around the country.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

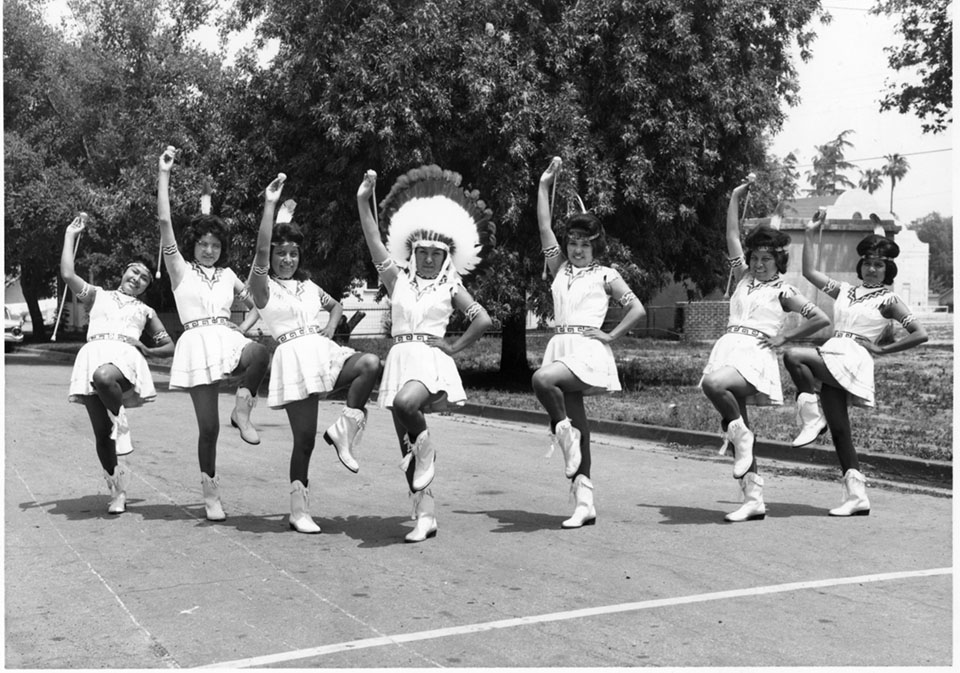

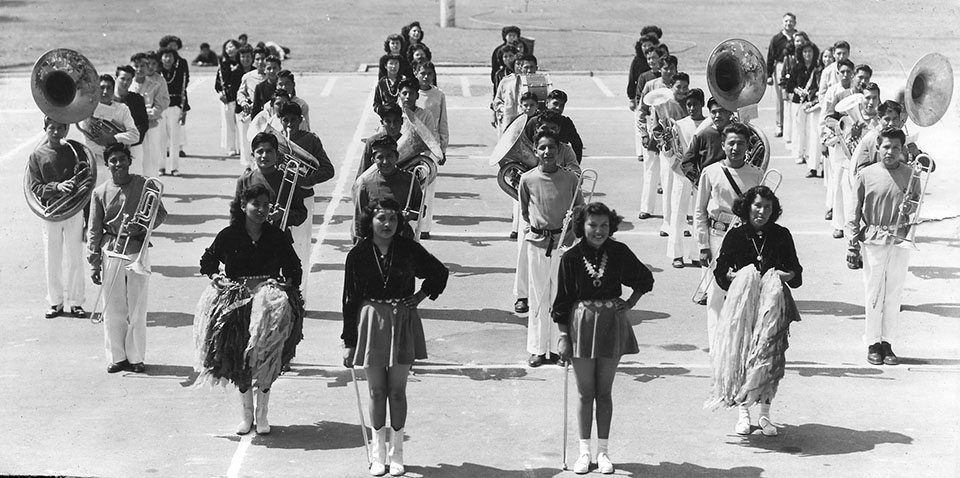

Students called themselves the Braves. In this candid photograph, baton twirlers wear headbands, concho belts, and cowboy boots. The lead twirler wore a Plains Indian-style headdress—which was not native to California.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

A girl poses in her tribe’s traditional dress. She would have learned to play the violin at Sherman. The book’s authors believe the image aims to demonstrate the school’s success at assimilating its students.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

A student float for “Sherman Day” at the Sherman Institute. The tipi motif was likely a tongue-in-cheek gesture.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

Girls pose during a Christmas party. Students generally stayed on campus to celebrate the Christian holidays with their “Sherman family.”

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

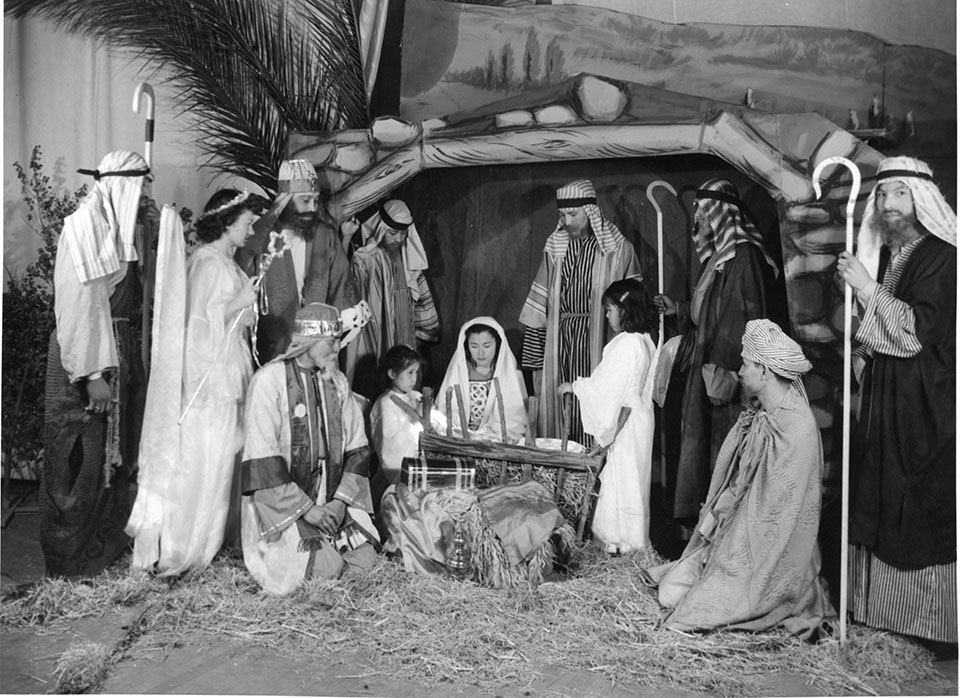

As part of the Christmas celebration, teachers organized a student Nativity play.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

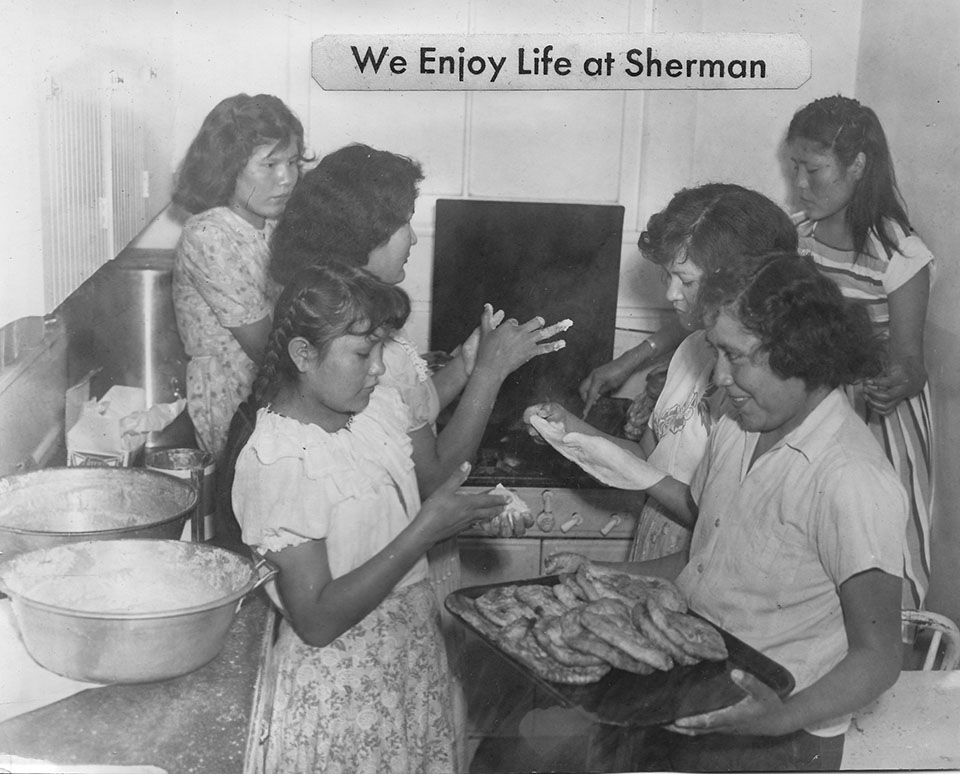

School officials hired photographers to create propaganda photos depicting the “joys” of life at Sherman. In this one, Navajo girls make fry bread.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

Social functions were designed to “civilize” Native American children. Instructors put on a formal dance for students in the Sherman gymnasium.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum

Sherman alumni sing the school fight song, a tradition at the institute’s annual reunion.

Courtesy of Sherman Indian Museum