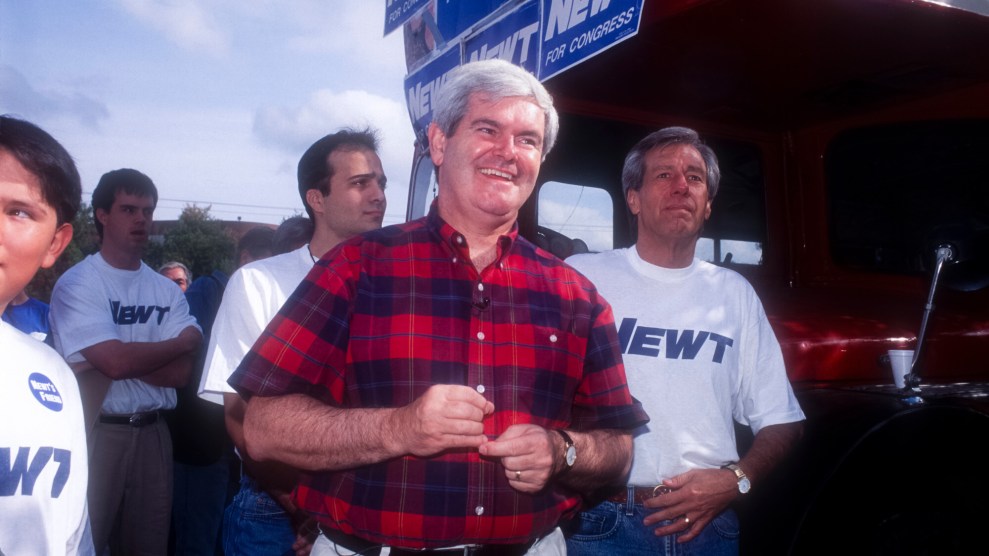

Jose Antonio Vargas with his grandfather in California. Photo courtesy of Jose Antonio Vargas

When Jose Antonio Vargas came out as undocumented in the pages of the New York Times seven years ago, he had no idea what would happen next. Before he published that essay, “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” Vargas was best known as a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter. He’d achieved the career he had been working toward ever since he was a teenager, all while keeping his immigration status carefully hidden. To come out publicly would be to risk throwing away his life in America. “One lawyer went as far as calling it, ‘legal suicide,'” Vargas writes in his new memoir, Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen.

Vargas did it anyway, providing a candid account of the years he spent hiding his status after his mother sent him over from the Philippines at age 12 to live with his grandparents in Mountain View, California. The revelation thrust him instantly into the center of the immigration debate. Since then, Vargas has been on the cover of Time magazine, produced documentary films, and founded a nonprofit called Define American, which seeks to change how immigrant stories are told by the media and entertainment industries. He’s even had a school named after him: Jose Antonio Vargas Elementary School is scheduled to open in Mountain View next year.

In Dear America, which comes out today, Vargas tells the story of his tumultuous 25 years in the United States, his experiences of “coming out” (first as gay, then as undocumented), his newspaper career, and his newfound role as an “activist/advocate/whatever-this-was.” He’s explored this territory in his earlier work, but Dear America may be his most personal effort. Vargas writes with a newspaper reporter’s spare, forceful prose, but he’s searching and highly introspective. And he wanted, he told me, to explore what he describes as a “mental health crisis” among immigrants in America.

Vargas recounts his tense encounters with Fox News hosts—like the time Tucker Carlson joked about having him deported—and his complex position within the immigrant rights movement now that he’s “the most privileged undocumented immigrant in America.”

He also interrogates his own fame, which, in 2014, helped him get out of being detained by immigration officials in Texas: “I didn’t want to know that while most undocumented immigrants are arrested, detained and deported, without due process, I was able to get out after eight hours of being locked up.” Yet he’s quick to point to the common ground he shares with millions of other undocumented people. “The contours of our experience,” he writes, “are much the same.”

Mother Jones: Since 2011, you’ve told parts of your story in articles and a film. Why a memoir?

Jose Antonio Vargas: Well, I really didn’t want to write a memoir. When I was writing it, that’s not how I was thinking about it. Once my editor and I settled on the structure of the book, which is [three sections called] “Lying,” “Passing,” and “Hiding,” it took on a life of its own. Having that structure allowed me to really investigate my own psychology. The book is really about psychological trauma: these stages that an undocumented immigrant goes through to just exist in this country. When I was writing it, it became very apparent that it’s not only undocumented people who can relate to that—having to lie and having to pass. You can argue that the whole arc of American history is about passing as American…

A friend said to me that reading the book felt like getting to know me for the first time, which I thought was interesting because I thought I’d already shared a lot of things, but apparently, I haven’t, really. When I think about it, in many ways I think I did this book to make sense of myself.

MJ: What did you learn?

JAV: I didn’t realize how much I’d been hiding from my own friends and people who were close to me who had always had a problem getting close to me. This has been a very challenging few years, especially after the election of President Trump, and I went to this really dark place in which I didn’t want to go out, I didn’t want to see anybody. I get asked a lot to go on television to talk about immigration—I said no to lots of them. I wanted to figure out my emotional state, but also how we got to where we got. Originally, I was going to write a migration manifesto, but the book took on a whole life of its own. I said things in this book that I’d never really said to my own friends, my own family.

MJ: Your New York Times essay ran during Obama’s second term, before the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy. Would it have been different had it come out in the current political moment?

JAV: Oh yeah, totally different.

MJ: Would you still have done it?

JAV: My biggest regret is that I didn’t do it sooner. I could have done it in the Bush era, when I was still at the Washington Post covering the 2008 campaign. There were many moments in my career, during my 20s, when I was surprised I didn’t just blurt it out loud.

What’s interesting is there are people who have read the book who are surprised [it] is not all about Trump, given that Trump has put immigration front and center. Honestly, I think if I had called the book Dear Trump—anything Trump—people would be interested. But that would not have been accurate, given that what we’re living through has been a culmination and a manifestation of both Democratic and Republican administrations. I date that all the way back to the Clinton presidency. I mean, clearly, this has been a horrendous, terrible time. The only analogy I can think of, historically, is the 1920s. But this does not happen overnight; it’s been policy after policy, a bipartisan mess that both parties are responsible for.

MJ: In the book, you go much further back, to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, for example. Why was it important to include that history?

JAV: Gore Vidal called the United States “the United States of Amnesia.” For a country with a relatively short history, especially in comparison to the Indians or Chinese or Europe, the American public in general—this has been my experience traveling around the country—don’t know much about our own history. That’s why you have people saying, “My great-grandparents did it the right way.” Wait a second: what right way? [There are all these] misconceptions about quote-unquote “legal” migration and how illegal migration was created. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act benefited immigrants from Asian countries, but did not benefit immigrants from Mexico and other countries. As much as we talk about Mexico in this country, and as anti-Mexican as this country has gotten, most people probably don’t know the complicated, tortured history of US-Mexico relations. So that’s why. History gives us a lot of answers. And I feel strongly that we have to really study it and really face it.

MJ: You’re pretty critical in the book of how the mainstream media has covered immigration. Have you seen any improvements in the past couple of years?

JAV: It’s interesting that it took Trump getting elected for many members of the mainstream media to finally understand the moral corruption and the inhumanity of the issue. If you look back to the coverage during the Obama era, you see how willing political reporters are to keep just politicizing immigration and not look at it as an issue directly impacting families. It’s been interesting this summer looking back at the coverage of the Central American refugee crisis, especially with kids being detained and locked up in cages. If you compare that coverage with the coverage it got in 2014, it’s pretty remarkable.

However, I still think there’s an oversight when it comes to connecting the dots between the demographic changes that are not only unprecedented but irreversible. You cannot separate the undocumented population from the documented population. In the next 50 years, according to Pew, 88 percent of US population growth is going to come from the immigrants in this country. And yet when we talk about America, for the most part, I think there’s still the propensity to talk about a black and white America. Whenever we talk about Latinos and Asians, it’s very politicized and one-dimensional for the most part. That’s why the success of Crazy Rich Asians has been so important. That’s why Jane the Virgin has been so crucial. But those are two examples. We need more.

MJ: Do you still think, given the actions of this administration, that your celebrity offers you some protection, or might it be a double-edged sword?

JAV: I don’t know. What did James Baldwin say? “All safety is an illusion.” I was prepared for anything and everything seven years ago, and I think that’s even more true now.

MJ: I was really interested in the parallels you draw between the LGBTQ rights movement and the immigrant rights movement.

JAV: I think it’s important to underscore the parallels—this whole idea of “coming out.” These are both movements that have benefited from the people who are directly impacted telling their stories. When I look back at being gay in the late ’90s, during Will & Grace, during the rise of Ellen DeGeneres, those were cultural moments. The No. 1 show on television was Will & Grace, and it was about this gay man with a straight best friend, and they were roommates. I like to say that for every Will, there’s a Grace. That’s been kind of a model for how we do our work at Define American. Clearly, Define American was founded and led by an undocumented person, but this issue is not only about the undocumented immigrants who live under these conditions, but about all the people that allow people like us to pass, who are hiding people like us.

I did this event in Aspen a couple months ago. After the event, this man came up to me and said that he employs thousands of undocumented workers. And I was thinking to myself, I wonder what would happen if anybody who’s ever employed or done business with an undocumented immigrant, if they all came out together and said, “This is what I’ve been doing for decades now.” To me, it’s this national need for us to really face the issue, which means facing people’s stories.