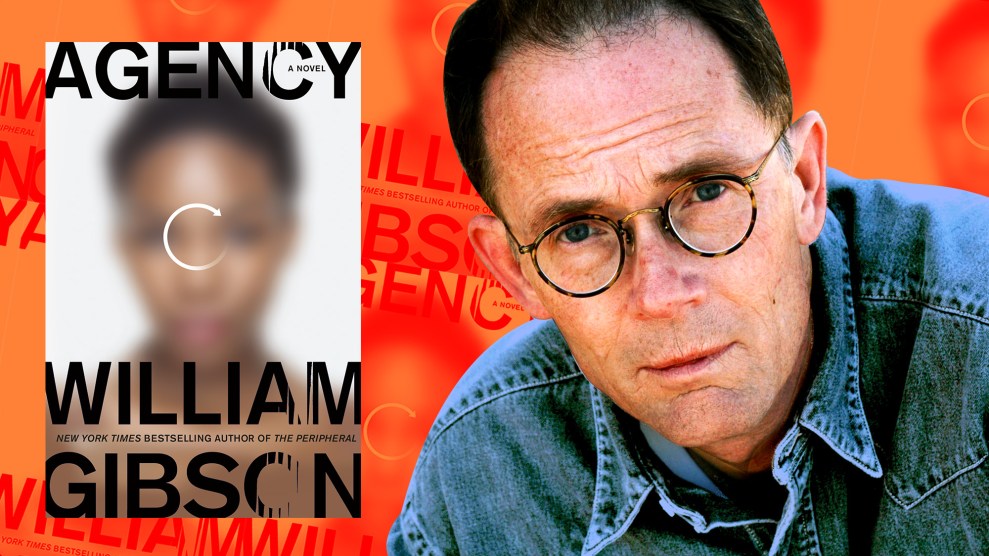

Ulf Andersen/Zuma/Mother Jones illustration

There are many alternate futures. But what if there were also… alternate pasts?

That’s the premise of William Gibson’s latest novel, Agency. Gibson is the pioneering science fiction writer who coined the word “cyberspace” and whose 1984 debut novel, The Neuromancer, inspired The Matrix.

In, Agency, the second novel in Gibson’s Peripheral trilogy, we’ve arrived back in 2017, at a fork of the past, called a “stub,” in which Trump was never elected and Brexit never happened. In this stub of 2017, an app-whisperer named Verity Jane is testing a beta super AI named Eunice, and crisis communication expert named Wilf Netherton has teamed up with a cop named Ainsley Lowbeer to try to avert a nuclear war. In other words, it’s a novel that looks unflinchingly at the importance of choice and the complex decision trees that could precipitate, or prevent, the end of the world as we know it.

Mother Jones Editor-in-Chief Clara Jeffery sat down for a conversation with Gibson at Public Works in San Francisco last January to talk about his new book. They discuss how politics has influenced his writing, and how the real-life climate crisis intersects with his fictional imaginings of the end times.

Read an edited transcript below, or listen to a recording of their conversation on this bonus episode of the Mother Jones Podcast.

There’s so many cool concepts in both of these books. But was there a particular one that got you on this path that you really took ahold of when you started the process?

I had been working for about two years on the beginning of a completely different book. I had described the book to my publisher as a satiric romp through contemporary Silicon Valley. Another time I described it to them as like Thelma and Louise, but really upbeat. That got me some really weird looks. Then one day I was on Twitter and I saw the video of Trump coming down the escalator to announce his campaign. Oh yeah! And all of my bad scenario gears stirred uneasily, but, you know, I’m not going to worry about that. Then one day I woke up to see that the Brexit referendum had passed in the UK and I thought, “Holy shit, if the UK can do that, and that’s all so stupid, the United States might actually be able to elect Trump.” And I thought, “No, it can’t happen.”

And then I woke up after November 6th and looked at my manuscript and it was set in a zeitgeist of 2017 that I knew was never going to exist. It had been made obsolete by the outcome of the presidential election, in this shatteringly absolute way. It really messed me up for about three months. I really felt like I had a head trauma or something. Seriously. I found myself, for the very first time in my life, questioning the reality of what I was experiencing. I was kind of going on like, how the hell could that be really happening? And I thought, what if it’s not? And then I happened to look over at my open laptop where the manuscript for my dead novel was. So I thought, okay, it’s a sequel. It’s a sequel to The Peripheral. After that it was just like years of work and missing hard deadlines and having the most patient man in publishing my publishing company. And then finally it’s here.

The book never names Hillary or Trump. And I was going to say that in some ways it feels like a lament, but maybe it was just denial for you? I mean, was this how you processed your grief and worry by…

No, it wasn’t. I don’t know. It was some sort of decision, but it was an organic decision. I mean, from the evidence of the text, it can be nobody but Clinton and Trump. There’s his behavior on stage with her during the debate… it’s him.

There’s a piece of graffiti that says, “lock her up.”

Yeah, it’s him. And everything that’s said about her, you know, it’s her. It felt to me like I would break some sort of spell, maybe just for me, if I named him. It felt to me that if I named him somehow it made it too on the nose. I don’t know, but I don’t think I would’ve been able to do it if I had to see his name over and over. Or even her name over and over.

You’ve said that as a child of the 50s, and same as a child of the 70s, we kind of went through early childhood really believing that the world could end at any time, and that that sense of imminent nuclear annihilation ebbed after the Cold War ended—or whatever it did. But now it’s back. And I’ve seen on Twitter that people are kind of constantly asking you, are we in “the Jackpot”? Which is that apocalypse that moves very slowly. So, are we?

I don’t think this is the beginning of the Jackpot. But some people are asking, quite unrelated to my book, the equivalent question: did climate change began 100 years ago, 200 years ago? We know when it began to change, but when did the trends in human behavior start to become set in certain ways? If it’s really coming down, we’re not going to be around for the end of it. It’s going to take about 300 years. It doesn’t make any cultural sense to us. The apocalypse is like, “bang.” We have this thing that we’ve been doing for so long. For at least 100 years, maybe 200 years. Some people are dating it to the emergent technology of agriculture. That’s when it began. This is a tragedy of unrecognized consequences, of actions we take for granted, and that we’ve regarded as wholly good things.

You’ve always had an uncanny ability to write about technology that doesn’t exist or certainly isn’t widely known, but that then comes to the fore. Do you study cutting edge research or are you just a time traveler come to warn us like Wilf?

No, I’m lazier than that. I just walk around. And when I’m my normal human self, and not actually sitting at a computer writing fiction, I walk around with sort of an eye peeled and looking for little bits of new stuff, or sometimes old stuff that we’ve sort of forgotten about, but that could, if it got into sufficient circulation, really change things. I see that as often how technological change happens. It’s never the stuff that the people who invent the technology or develop the technology think is going to happen. That’s never the stuff that causes the big change. It’s stuff that nobody anticipates.

I think most people, or at least popular culture, present all powerful AI, generally, as a completely ominous thing that’s probably gonna, you know, kill us. The Terminator and The Matrix, movies like that have really trained us to think about things that way. So Eunice offers a different view of what that could be. How did you start imagining it differently?

I was always deeply unimpressed with the way AI was presented. It’s either like godlike benevolence, godlike totally pragmatic uncaring, or godlike pure evil. And I go, no, forget the “godlike.” The first time I read about or heard about the theory of the singularity. I was immediately totally uninterested in the idea of the pure singularity. I thought, what about a half-assed singularity? Some kind of half-cocked shit, but it’s so powerful. And that really turned me on. I don’t know what it is. It’s just the way my mind works. I also like to think about pissing readers off who would just hate the idea of the first sentient, really, really powerful AI being a black woman.

You are such a tactile writer. You have such an eye for fashion and style and detail and just closely observed things. So I’m wondering when you’re writing, what part of it is distilled observation versus pure imagination? How does that synthesize for you?

I suspect it’s more observation than pure imagination. One thing I’ve found really fun about The Peripheral was that, in the 22nd century thread, I got to imagine these totally off-the-wall science fictional things. Like the thing that comes to kill Daedra or her sister or whoever it kills… I’m losing it. I’ve already lost the plot line to that one. But it comes like flipping it’s way up the side of the skyscraper, and it’s just not like anything that’s ever existed, except it does look kind of like a particular kind of egg sack I used to see as a kid on the beach in South Carolina.

There’s a very good New Yorker profile that came out recently about you, and there’s this amazing detail of how a bomber jacket variant that you describe in Pattern Recognition started to be demanded from fans to make that jacket. It was not sufficiently authentic to the 1940’s thing. But then they made it anyway and, with your help, now you see it everywhere, especially in tech circles. I’m imagining a few people are probably wearing it here tonight. But then another marketer called K-HOLE turned the fashion philosophy of your protagonists into the sort of beginnings of the notions of “normcore.” So says the New Yorker. But essentially, you sort of recoded fashion. And that’s not too far off from what the klept are doing in the stubs.

Well, that’s true. That’s true. But in both cases I had no intention of so doing. Like it wasn’t as though one day I was sitting at my computer and I thought, you know, I’m going to take the MA-1 bomber jacket, which is one of the most iconic pieces of American military clothing of the 20th century, and I’m going to make it even more iconic and popular. It would have been crazy. But through this sort of odd course of events, I think, I’m not positive, but I think I may have contributed to an increase in popularity of copying that pattern. But to deliberately do it, I don’t know. I’m not even sure it could be done. If somebody could go, okay, I’m going to do this now, it would be really scary.

We’re in San Francisco. You set much of the Bridge trilogy here, which had a sad forecasting of the explosion of homeless shantytowns that we see now. Agency is largely set here. What is it about this city? I know you’re fascinated with London and Tokyo, but what is it about this city that you’ve wanted to explore?

I think it’s because I’m an American who’s lived in Vancouver all my adult life. And that’s probably one of the reasons that in Neuromancer you can’t prove from the text that the United States still exists. The cities are still there, but from what the text says, they might be like independent city states or something, owned by multinational corporations. The United States is never mentioned as an entity. At that time I was covering my ass because I didn’t know the United States. When I started selling books and I started touring, San Francisco was the place that made the sort of impression that allowed me to write about it. Like my imagination works differently here. Or when I’m writing an imaginary San Francisco, I’m just sort of able to do it. I’m comfortable with it, and in some way and I don’t think there’s really much much else to it.

Can you unpack, say Verity Jane’s name? I’m curious about the meaning behind some of the names. They seem to be multilayered, like I’m in inception going down through that name.

I don’t know where Verity Jane’s name came from. I don’t remember. And that’s not atypical of my process. I have no idea why Flynne Fisher in The Peripheral is called Flynne Fisher. I know that Henry Dorsett Case is named that because… I forget where the Henry came from, but the Case is from an iconic brand of the 19th century, and still surviving, American pocket knife. And Dorsett was the surname of a dear friend of mine, who’s now been dead for 20 years. Richard Dorsett, who is a sort of running mate of the Austin cyberpunks, and just a really smart creative guy who didn’t have to bother with writing fiction. Cayce Pollard… I don’t remember where the Pollard came from, but I named Cayce after Edgar Cayce. But I didn’t know that Edgar Cayce’s name was pronounced Casey. All my life I’d been saying Edgar Case in my mind, and I never had cause to talk about it with anyone. It’s more the way they sound than any any meaning they might have. But if they seem to have potential to cause a reader to scratch her head, that’s sort of viewed as a plus too.

We’re in the middle of a real timeline where hackers helped elect a kleptocratic president who acts on behalf of oligarchs and is running a scheme to dupe the public aided by malevolent media forces, ignoring runaway inequality and a clear and present danger to the world’s ecology. When can we expect the next book? And do you think you need to know the results of this election to finish it, or maybe even to start it?

There are a lot of little ways in which Agency is shaped, and a lot of little moving parts in Agency’s structure that a reader probably wouldn’t notice. Particularly because you wouldn’t notice them until it would be necessary to turn the thing. It’s like I was creating a kind of universal joint. And the joint is there to avoid disruption by current events. Like a nuclear war would take it out. Because I think we would know if there had been a nuclear war in the history of Wilf world.

How big a nuclear war are we talking, really? You know maybe a little small nuclear war could be part of the jackpot…. I’m just kidding.

Today I was reading about shutting down another city in China to try to contain that coronavirus. And I’m remembering Netherton’s wife says, she’s talking about this 2017 stub and says, “it’s not too bad there.” It’s before the pandemics anyway. And that kind of thing. Like I’ve got the pandemics covered. I’ve got all kinds of stuff covered, up until the election of President Gonzalez. Actually, if there’s a female president elected this year, it’ll blow my universal joint. And, okay, I would welcome it still.