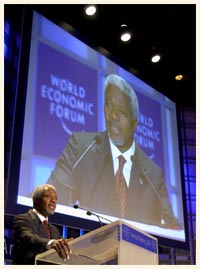

Image: AP/WideWorld

New York — Critics of globalization often refer to the corrosive influence of “the West”, as if the Northern Hemisphere, bookended by Los Angeles and Moscow, somehow acted as a cohesive whole. Judging by the mood inside the plush meeting rooms of Manhattan’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel as the World Economic Forum eased to a close, those critics may need to fine-tune their rhetoric.

The meetings, normally held in the Swiss resort town of Davos, have been decried by many as little more than an economic high-rollers’ party, a showcase for the West’s corporate-led global capitalism. This year, the party was as glitzy as ever and drew the expected cadre of corporate leaders and government power-brokers. But cohesion was in short supply.

The meeting’s final days were marked by a clear rift between European and US attendees, caused in large part by the perceived haughtiness of several notable American officials. And while many WEF stalwarts sought to keep the focus on how corporate leaders must consider all the world’s ‘stakeholders’ in their global strategies, it was the Bush administration and its strategies that dominated the debate.

Secretary of State Colin Powell caused a row when he insisted that the U.S. would not hesitate to strike against its enemies without the consent of its allies. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill added fuel to the conflagration by voicing the administration’s objections to propping up nations like Argentina, which descended into chaos after the U.S. ended emergency aid.

|

||

But the deepest rifts appeared in the debate over America’s handling of captured Taliban fighters, which has been generally portrayed as barbaric in the European press. Irene Khan, secretary-general for London-based Amnesty International, voiced her organization’s deep concern over the treatment of prisoners being held at a Navy base in Cuba, as well as the US proposal to try some detainees before military tribunals.

“There is no need to create a shadow criminal justice system to deal with these threats,” said Khan. “It’s very simple — when people are arrested, they should be charged with a crime; they should have access to a lawyer.” European business leaders, crossing one of the rhetorical divides that has marked past WEF meetings, took pains to echo Khan’s concerns about Washington’s policies.

The US delegation, led by Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), was just as quick to defend the administration’s refusal to consider captured Taliban soldiers prisoners of war — a decision that has allowed the US to bypass Geneva Convention rules on interrogations and access to prisoners. James Kalistrom, a top-ranking FBI official, dismissed the decision as simply a necessary evil required by difficult times.

The chill between the US and Europe extended to more mundane issues, as well. Participants from the continent wondered aloud whether the Bush administration, which has exhibited its distaste for international accords ranging from the Kyoto climate agreement to the ballistic missile treaty, will begin ignoring certain sections of international trade pacts that it deems similarly inconvenient.

If the US continues to act unilaterally to protect its interests, many WEF members fear, the future of globalization may be at risk. And globalization, the forum’s leading lights insist, is the key to world peace. In a spin on the old political science theory that robust democracies don’t fight each other, these WEF participants hold that nations with intertwined economies won’t go to war.

“Globalization has proven to be of advantage to the people of the world,” argued Horst Köhler, managing director of the International Monetary Fund. “The integration of nations was upset before through nationalism and protectionism, which led to two devastating wars.”

That belief in the importance of economic harmony was at the core of another key concept trumpeted in the Waldorf’s meeting rooms — the CEO as statesman. Executive after executive cooed about their new obligations: To care for the Earth’s downtrodden in addition to their shareholders. Richard D. Parsons, AOL Time Warner’s CEO-designate, waxed philosophical about the evolution of governance, from divine-right monarchies to elected democracies to, finally, corporate oligarchies.

“We are at another point in evolution where we are inheriting the responsibility for structuring social order,” said Parsons, “when the bulk of decisions as to how people are going to lead their lives, about what opportunities they have, what access to opportunities they are going to have, is migrating to the corporate sector.”

Not everyone at the Waldorf welcomed that shift, which some suggested will do little but undermine democracy.

“How can someone who was appointed to the board of Shell decide how society should be run?” asked Martin Wolf, columnist for The Financial Times. “At that point, you’re getting involved in the political process.” And that, Wolf said he fears, is a shift that is putting the power for public welfare in hands that, inevitably, must bow to the demands of shareholders.

The new breed of CEO statesmen haven’t exactly built the greatest track record when it comes to aiding and empowering the disadvantaged — a fact noted by United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan in his closing addresss. Annan pointed out that of the 1,322 medicines licensed worldwide between 1975 and 1997, only four were created specifically to treat tropical diseases. Jeffrey Sachs, director of Harvard University’s Center for International Development, underscored that discrepancy when he loudly denounced the West’s commitment to confronting the AIDS pandemic in the developing world.

“Not one single human being anywhere in the world is receiving an anti-AIDS drug as part of a program funded by the United States,” Sachs said. An official of the American drug giant Pfizer, while expressing sympathy, responded by claiming that little can change until customers in Canada and France agree to pay more for prescription medicines — a balance of social need and profit margin that did little to support the CEO-as-statesman model.

Despite the stalemates and the divisions, WEF attendees left the Waldorf on an upbeat note. With the forum’s setting and timing conspiring to keep protest muted and at a distance, participants left New York seemingly reassured that the globalization train cannot be derailed.

In a farewell toast, WEF president Klaus Schwab thanked his staff for helping make the world a better place. As they sipped champagne and tucked into roast-beef sandwiches, most of the workers gabbed about their celebrity sightings (Dick Cheney, Bill Gates, Skeptical Environmentalist author Bjorn Lomborg, looking beefcakey in a skin-tight grey t-shirt) or their need for a good night’s sleep (18 hour days were the norm).

Still, it was the parting comment of another celebrity attendee — U2 frontman Bono — that was repeated in discussion after discussion. “The credibility of these kinds of forums is in jeopardy if we don’t follow through with real action,” the rock star opined, shortly before turning down the WEF’s most prestigious award.

Unfortunately, the “real action” Bono called for sometimes affects the bottom line. And as Wolf and others clearly pointed out, that is the lasting dilemma for the CEO’s-cum-statesmen of Davos on the Hudson.