Image: AP/WideWorld

Her most recent work, S.: A Novel of the Balkans, explores the brutal ethnic conflict that tore through the former Yugoslavia. The novel, which delved painfully into the realities Bosnian women faced if they were unlucky enough to end up in a concentration camp during the war, was published two years ago in the US.

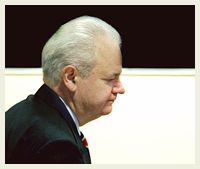

Her next book, due out in a year or so, will explore war criminals — specifically those on trial for their actions in the Balkans conflicts — and the popular desire to dismiss them as monsters totally unlike normal people. In a recent interview, Drakulic, who was in The Hague for the opening of the long-awaited war crimes trial of Serbian strongman Slobodan Milosevic, made clear that she rejects that way of thinking.

“Even today, I still think we need this tribunal, and I think we should be grateful that there is such a place, because if it was up to us, the people in Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia, we would let our criminals walk in the street,” she says. “And why? Because we don’t consider them criminals. We consider them heroes.

MotherJones.com: Danis Tanovic, the Bosnian film director whose film, “No Man’s Land,” won best screenplay at Cannes last year, has said that he thinks the Serbian people are angry with Slobodan Milosevic — not for anything he did, but for not going far enough. What do you think?

Slavenka Drakulic: Probably. I think the Serbian people were much more upset with Milosevic, and it’s visible today, because of what he did to them. They consider themselves the biggest victims of the last 10 years, and in a way they were right. His own people were also victims of their own regime. I think it’s an interesting example of victimology.

Even today they will say, ‘Oh, it’s good he’s on trial for war crimes, but we would prefer he be put on trial here for what he did.’ In a way they still don’t recognize that there was a war. They still don’t recognize that they started the war, that they were the aggressors. They still don’t realize that they participated. Milosevic didn’t kill anybody. It was Serbian men who went into the army, either drafted or as volunteers, and they went to Bosnia and Croatia and killed.

Right now, Milosevic is only a scapegoat. Because he’s on trial, the Serbian people will be absolved of their crimes. This is what I think is not just. There is no process of thinking and asking questions about “What did we do wrong in the last 10 years?” except for a very small minority, as there is no such discussion in Croatia. From that point of view, it would be better if these people would be on trial in their own respective countries, because perhaps then a process of catharsis would be triggered.

MJ.com: Much was made by Western observers in the former Yugoslavia about the importance of historical hatreds in understanding what was happening. How important do you think historical causes were in what took place?

SD: Usually when we speak about war criminals, we would like to believe that they are some kind of monsters, some kind of perverse people, people who are not normal — people who like to kill. We have this belief because it’s easier. When you isolate the people, you want to assure yourself that you would never end up as a war criminal, and you protect yourself in this way.

But researching them, and looking at them, it becomes obvious that the opposite is true, that they are in fact ordinary people. If we cannot consider war criminals in relation to our own life, then why should we put them on trial in the first place? Yes, they have to be punished, but one aspect of punishment is that we learn from them. I’m not sure if we learn anything from them if they are monsters. But if they are ordinary people, then you learn what the circumstances are that brought them into it.

History certainly plays a role. But it’s what happens with history, and this is political manipulation. It takes years and years of preparing the war through the media in order for this history to become important in individual lives, and for people to take this or that side. Otherwise, how could you explain that with the same history, people were capable of living together through 50 years of peace? It’s the same history. The question is: Do you leave it, or do you use it for manipulation?

MJ.com: David Halberstam and others have written that Bill Clinton read Robert D. Kaplan’s book Balkan Ghosts during his first term, and that it seemed to influence him toward this view of intractable historical hatreds.

SD: Maybe Clinton interpreted this way. At the beginning of the war, this was the general thesis. It was the easiest way out for many journalists who just flew out and didn’t know where they were and didn’t know the language and hadn’t read any books about the Balkans. The easiest explanation was “1,000 years of hatred.” It was really a cliche at the beginning, and then after a couple of years they realized it was too easy an explanation. Later on, I have to say, the articles and TV reports were quite good.

I was talking to a person at the Library of Congress in Washington, and she told me there have been more than 900 books about the war. I think it’s a fascinating number. Today, if somebody wants to know something, they can read about it, and the cliches about “1,000 years of hatred” don’t work any longer.

MJ.com: When you talk about the importance of seeing war criminals as ordinary people, at least in some ways, that sounds a lot like the work of the journalist Gitta Sereny, who did so many interviews with former Nazis. (A collection of Sereny’s work, The Healing Wound, was published last year.)

SD: She’s doing the kind of investigative journalism I would like to do, but my health is such I cannot travel so much. I read her book about Franz Stangl, the commandant of the Treblinka death camp, and this is where she shows step by step that he was an ordinary person. He was capable of separating his private life from the rest of his life. Hannah Arendt analyzes this as an aspect of modern life, people separating their private life and professional life. So you end up with a war criminal like Eichmann, who is actually surprised that he is on trial for something that he considered his job. He was only following orders.

The moral questions aren’t there. There don’t need to be, when your personal life and private life are completely divided. Sereny shows in that book on Stangl how these worlds can coexist. What is more important is we would like to believe that all the evil in the world is done by some evil men, and has nothing to do with us. But it’s all about us, it’s about ordinary people.

What she shows is how did it happen day by day. When you take it day by day, it doesn’t look so bad. One day you sign a paper, another day you sign another, and you don’t even think of how it accumulates.

War criminals do become criminals overnight, in a way, but there is a long way of adapting to the situation, where the other are turned into nonhumans. Our moral code forbids us to kill someone who we consider human, but if you manage to turn the other into someone who you consider nonhuman, then it is not such a big problem. To come to this point takes a lot of time for psychological preparation. In a way we all participate in that. We all accept that. We are responsible. Because we make war criminals, in that sense.

MJ.com: What’s your perspective on the War on Terrorism? Do you see a similar attempt to turn enemies into nonhumans?

SD: There is no other way. To make a war, you have to turn them into nonhumans. I am trying not to watch so much of that on television, but one thing I’ve heard is if you think America is our model of democracy, then you also cannot understand how it’s so easy that all the so-called free media turn into the state propaganda media. I think it’s absolutely astonishing. This is not what we expected.

We think this is the most advanced democratic world, and that the media there are the most free, but now we see that in the moment, now, it’s like putting on another coat, of ideology, and they are all now in the service of state propaganda. This is to me astonishing, and it’s also dangerous. Americans swallow everything that is given to them by the mass media. That’s the question: How free is the media? I don’t think they are free at all.

MJ.com: What do you think of Milosevic’s performance this last week before the War Crimes Tribunal in the Hague?

SD: I think it was very much expected, but very good. I think his speech is not going to help him very much in his defense, because it wasn’t a defense speech, it was a political speech. His aim was political, to discredit NATO. And I have to say that after he spent hour after hour after hour, listing civil objects like bridges and maternity wards and factories and roads and civilian houses, and also listing civilians and showing pictures of dead civilians, I have to say this was very effective in discrediting NATO.

It’s one thing when you say, “NATO bombed us unjustly and killed civilians,” and it’s another when you spend so much time listing. It had quite an effect, I can say. This is one reason why CNN censored him the second day. They didn’t want to show him any longer.

His aim was to discredit NATO, and that’s his right, but it will not help him with his defense.

The question is: What is he going to do next? I think that was partly answered on Tuesday. He cross-examined the witness of the prosecution, which means that in spite of him saying that he didn’t recognize the court, and it’s not legal, nevertheless he’s completely involved with the process. He will always try to deliver political speeches, and try to put the blame on NATO. He doesn’t recognize there was any kind of war and that he was to blame. He was in his view a peacenik.

You can see he’s very much ready to defend himself. He’s not depressed or something. This is a man who is ready to fight. He’s not giving up in any way. He will involve Bill Clinton and Tony Blair and Madeline Albright. He will call them all as witnesses, if he can. And I think they should come. But this will last two years, and I don’t know how good he will be at organizing his defense. Now it can be politics. Later it will to have to be the nitty-gritty details of the war and the answer to the 66 counts against him.

He can be very cocky now, but it doesn’t mean he will be cocky a year from now. My problem with Milosevic is this: I think that he’s completely separated from reality. He does not recognize reality, he does not want to discuss reality, he has his own construction that he calls reality. And this is a big problem. It’s almost like he would be a schizophrenic.

MJ.com: Isn’t that often true of absolute leaders, like, for example, Hitler, especially later in the war?

SD: Hitler or Stalin, yes. When you are such a person, when no one dares to tell you the truth, it makes you like this. People who have absolute power, people don’t dare to tell you things. As a President, Milosevic was more and more autistic, like an autistic child, in the sense that he doesn’t want to take reality.

MJ.com: And how will you explore this theme in your next book?

SD: What I would like to achieve is when a person reads my book, they will ask, “Could I have done this? Could I have committed such a crime?” Because if we don’t ask ourselves that question, then everything from Primo Levi to Gitta Sereny, writings about the Holocaust, that’s useless.

We always have to ask ourselves if we could have done that. We have to remind ourselves all the time that there is such a thing as moral choice. There is always the ability to decide. This is what makes us human. Sometimes it’s a difficult choice, but it’s always a choice.

War and war crimes are what we do to ourselves. We are participating in it, we are making it possible. If we don’t commit crimes ourselves, we are still a part of all of it. In other words, these people are not monsters, we turn them into monsters.

MJ.com: How do we do that?

SD: I think it starts with not saying “Hello” to your neighbor who is of a different nationality or a different race or a different color. It starts with the very, very small steps. And then, even without thinking, especially without thinking, you end up approving — a war, or war crimes, or fascism or whatever, you are in it.

It all starts with everyday, small decisions: Today I am not going to say hello to the neighbor. Tomorrow, you take the place of someone who has been taken away, without asking where he was taken away. It’s these kinds of decisions that make you a collaborator in fascism and war crimes. If Slobodan Milosevic is on trial, it doesn’t mean the people of Serbia are not responsible, too. For me myself, the same would be true for someone from Croatia who is on trial for war crimes. We are not excused if someone else is a scapegoat.