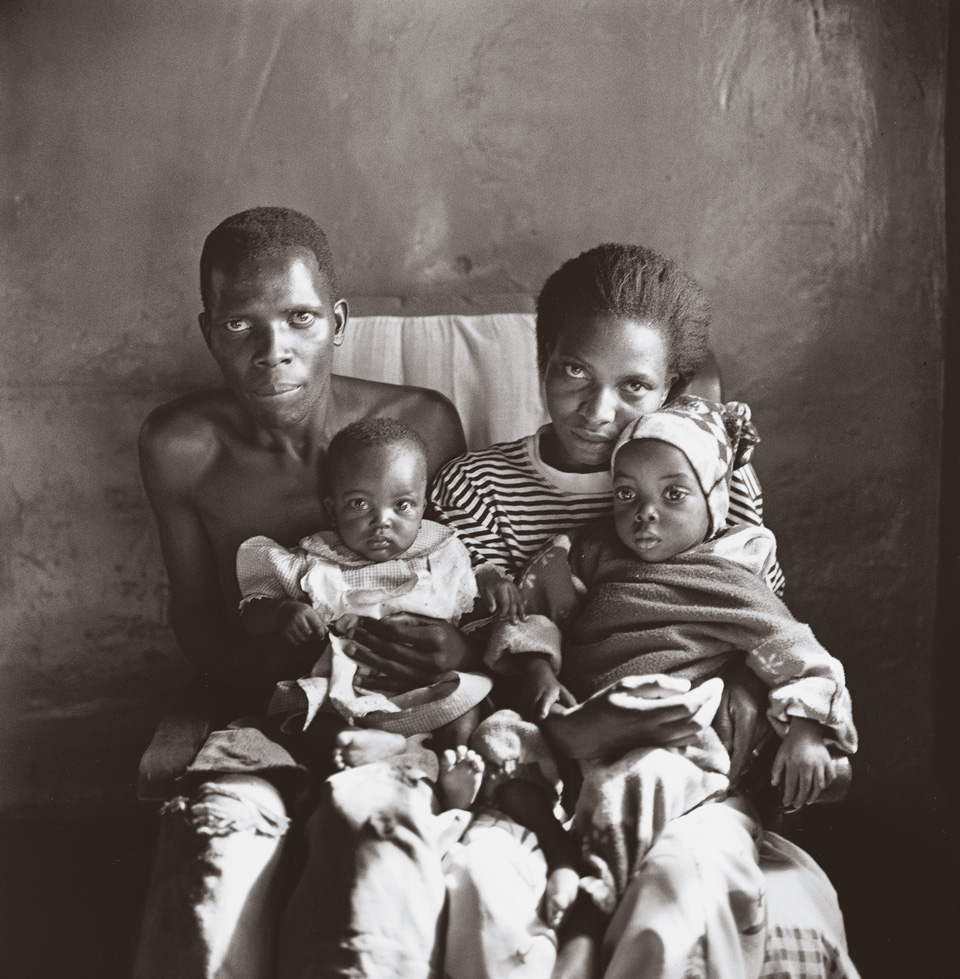

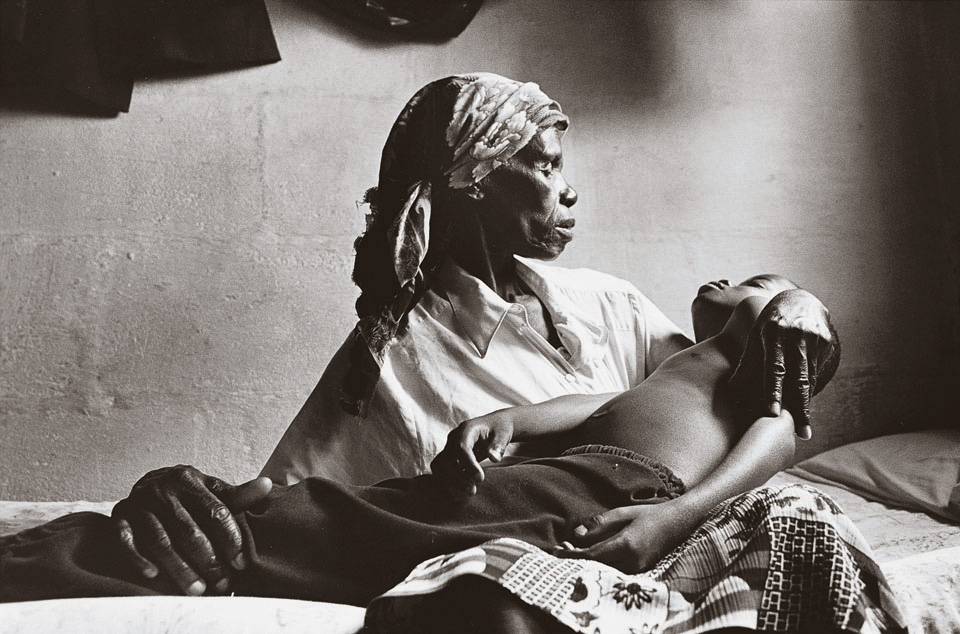

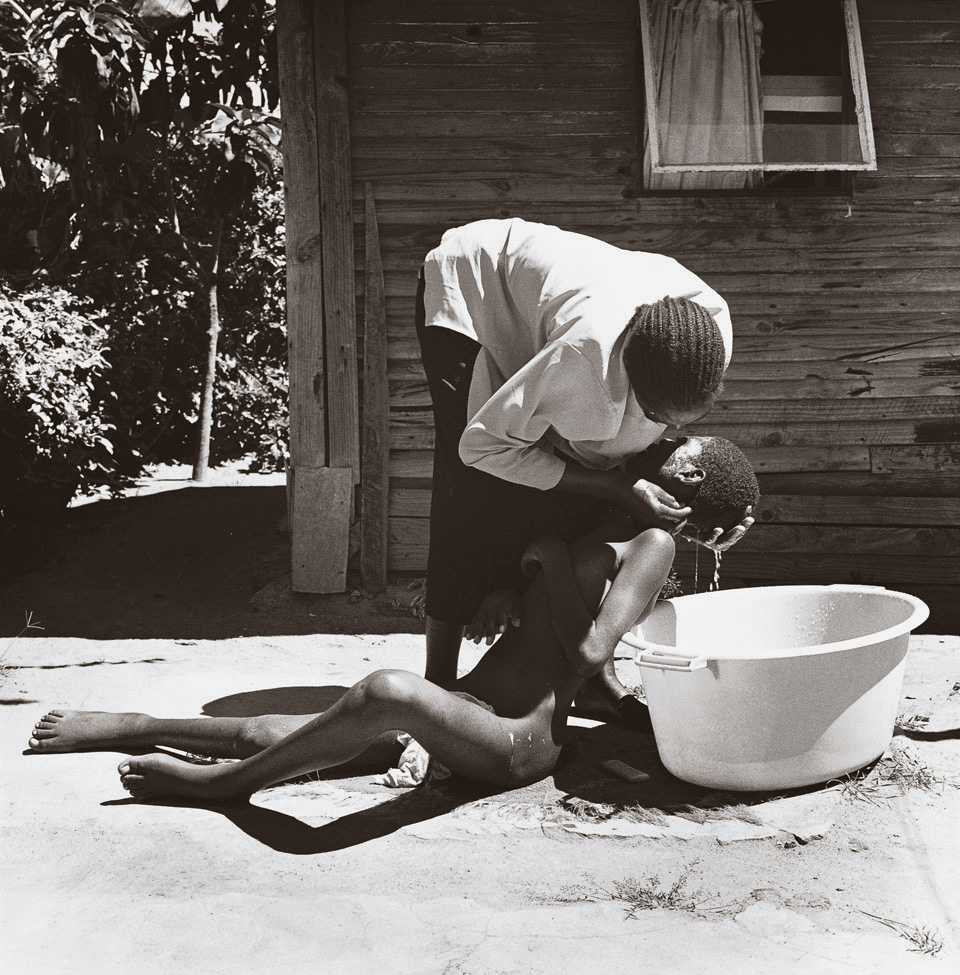

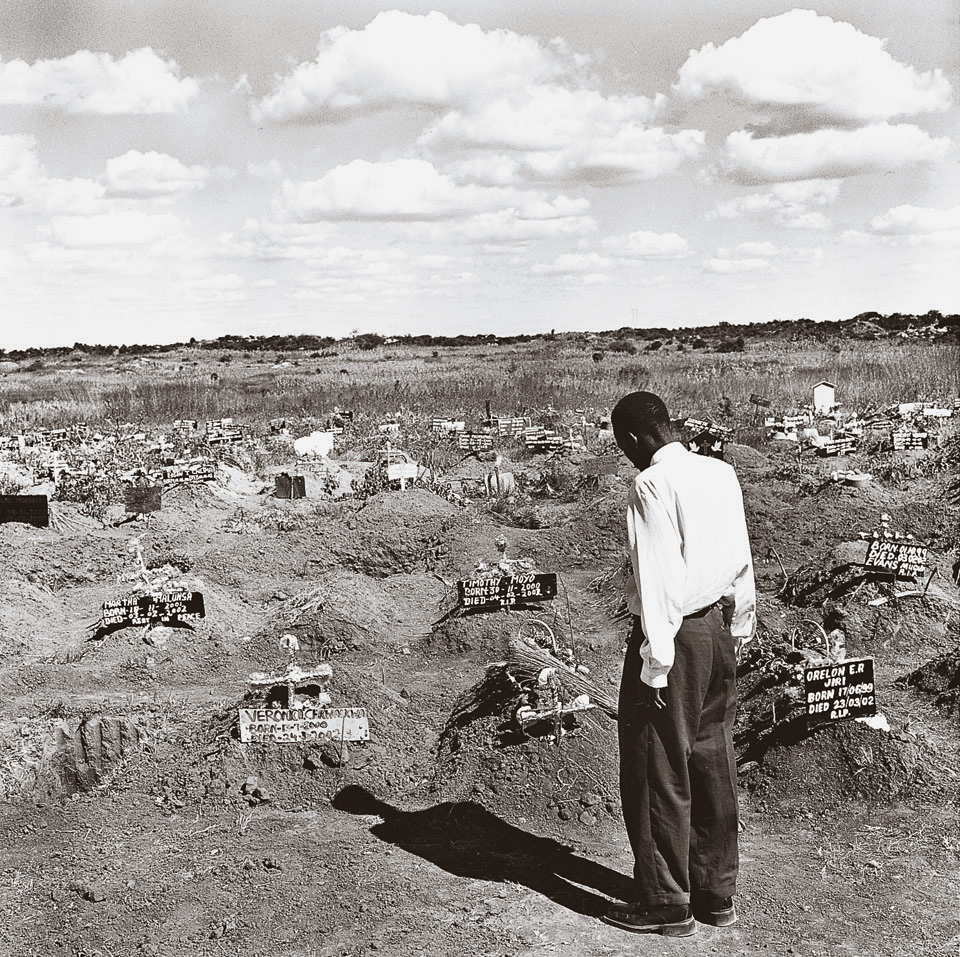

When the photographer Kristen Ashburn went to a township outside Harare in 2002, she came upon a woman carrying her grown son in her arms—intent on giving him a bath. For the past two years, 20-year-old Simba had been unable to walk or speak because an AIDS-related fungus had infected his brain. Taking care of him was a 24-hour job; even if she had been able to find employment in a nation where 75 percent are unemployed, and 34 percent are HIV positive, this woman could not have considered it. But statistics alone do not tell this story.

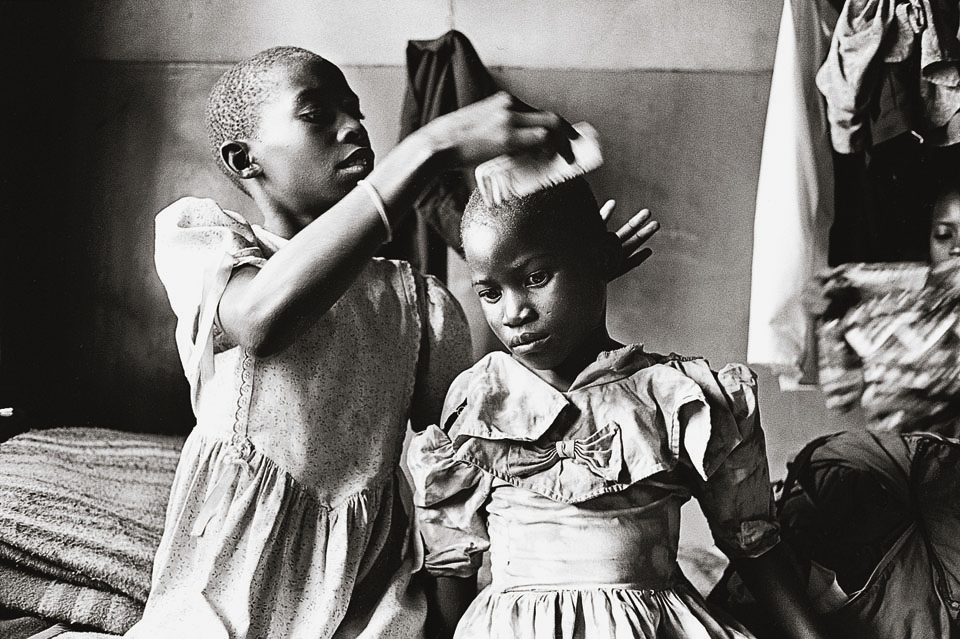

What Ashburn’s images convey is the tortured psychological reality behind them. A boy preparing coffins. Two children waiting for their sick mother to arrive. An aunt in grief for her nephew. A mother cradling her emaciated son. None of this is normal. What Ashburn’s haunting photographs may obscure, however, is that none of the people on these pages–no son, brother, sister, friend, lover—needed to die. I know of no photographer, journalist, or filmmaker who has traveled to sub-Saharan Africa and not been devastated by what they witnessed: people dying in genocidal proportions of a treatable disease. Last January, President Bush promised $15 billion, over five years, to sub-Saharan African nations and the Caribbean for AIDS prevention and treatment. Bush’s pledge appeared beneficent, but a third of the money he promised for 2004 did not materialize. Meanwhile, the U.S. government, in line with the pharmaceutical lobby, continues to push brutal, unfair drug patents on Third World nations, keeping life-sustaining medicines from 95 percent of the world. It has even worked to sideline the U.N.-backed Global AIDS Fund, which has endorsed cheap, high-quality generics. The fund is thus nearly bankrupt. It may come as a surprise to Americans that, in spite of the high-minded rhetoric, far less than 1 percent of African HIV patients are on anti-retroviral treatment today—an estimated 50,000 people—on a continent in which 34 million are infected.

Time will tell if the controversial WTO accord to export generics can improve access to treatment, but time, as these photographs make painfully clear, is a commodity that people with AIDS in Africa do not have. The Bush administration has also denied AIDS funding to African regimes it finds objectionable, including Zimbabwes. In an open letter to President Bush, T. Kujinga, founder of the Mutare-based AIDS organization, the Life Project, writes, “We are painfully aware that Zimbabwe is not listed as a recipient of the presidents philanthropy.” Zimbabweans are suffering under the double burden of a staggering HIV rate and President Robert Mugabe’s harsh policies, he adds, and “ought not to be excluded from any treatment initiatives…because of government to government hostilities.”

I wrote to Kujinga and received an extraordinary 12-page letter in reply. His story illustrates the maddening inaccessibility of treatment in Zimbabwe, even to the luckiest few who can afford it. Kujinga was a lawyer in private practice–a member of the elite. When a friend, whose wife had died from AIDS, became ill in 2001, Kujinga took him in with his two daughters. The friend soon died, and then, in August 2002, Kujinga discovered that one of the children was positive. “That was the beginning of my nightmare, and was to change my life and career.” What Kujinga then went through in search of anti-retroviral treatment for his daughter–“for that is what I consider her to be”–can only be described as surreal. He bought a months supply of a three-drug cocktail from a doctor, for which he paid $30, “a princely sum” (more than a third of his monthly salary), “but still affordable to a lawyer.” Over the next two months, prices doubled, but he was still able to purchase the cocktail from a local pharmacy. The next month the drugs became scarce, forcing Kujinga to turn to the South African black market to keep his daughter alive. Under Mugabe, Zimbabweans have seen not only massive human-rights violations, but economic devastation. Half the nation now needs food assistance. Inflation is approaching 700 percent. Just finding gasoline and getting to work is a terrible burden for most. Those few who can initially afford anti-retroviral treatment often cannot sustain it because of erratic supplies and hyperinflated costs. “Such an economic system,” he writes, “became a nightmare for me.” Kujinga soon gave up his legal practice to found the Life Project, which helps others find treatment. But he adds that most Zimbabwean AIDS activists are either indifferent to or do not know what anti-retrovirals are. “The situation is desperate and pathetic,” he writes. “People are dying without help and without hope. We now have more orphans than ever before. And our hospitals are flooded with pathetic skeletons of dead people walking.”

TK