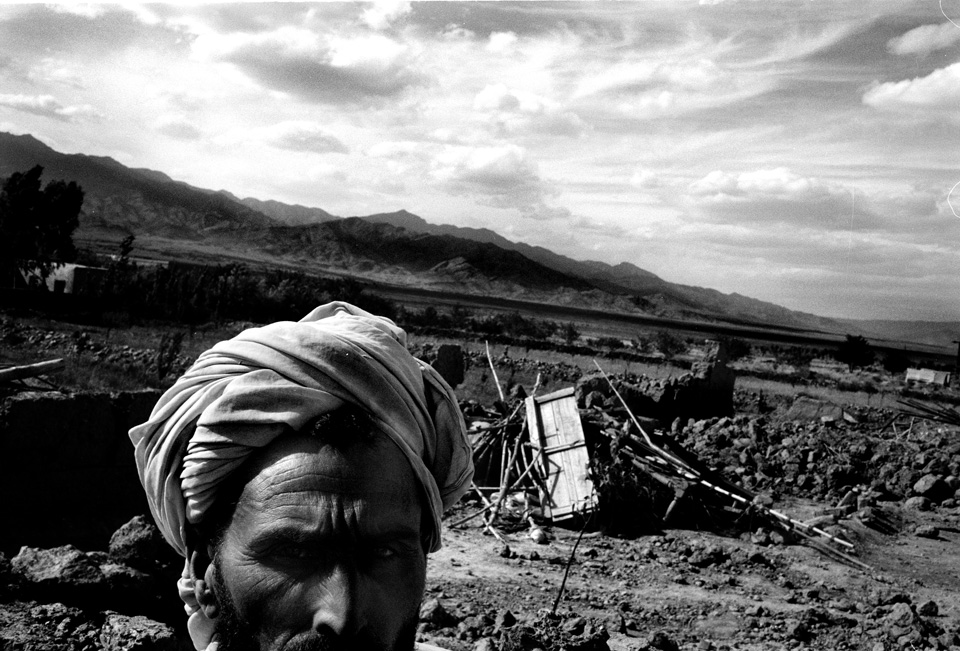

Mir Abbas Khan stares into the camera. Behind him the ruins of his home lay strewn across the dry, hard ground. Since March, when Secretary of State Colin Powell visited Pakistan and promised President General Pervez Musharraf billions of dollars in aid, the Pakistani army has been scouring the semiautonomous tribal regions of South Waziristan for Al Qaeda fighters—bombing, burning, and bulldozing the homes and belongings of those deemed collaborators, or merely uncooperative. Over the centuries, no one has exercised much authority over South Waziristan, a stark, mountainous area of southwestern Pakistan that borders Afghanistan. But in the wake of two assassination attempts, and in pursuit of continued U.S. largesse, Musharraf seems determined to try. At the start of the campaign, he announced that a senior Al Qaeda leader was surrounded, and hinted it might be Osama bin Laden. Days later, after the army met surprisingly stiff resistance, the top Al Qaeda operative was down-graded to a Chechen commander, and then to a local criminal. Eventually, senior government officials admitted they never had proof that a key terrorist was in the area.

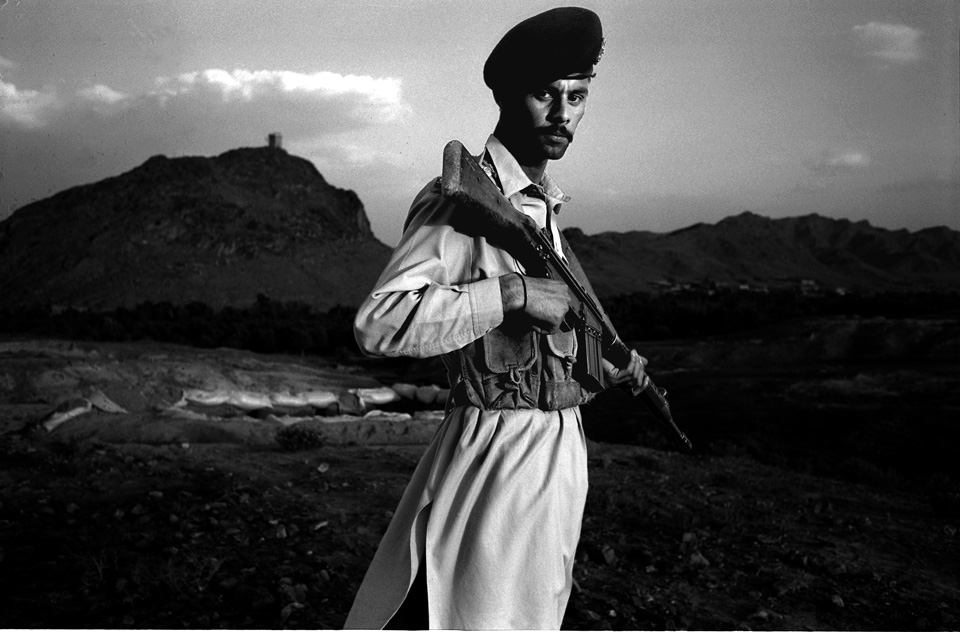

Though it boasts of killing hundreds of militants—claims that cannot be substantiated—the government is tight-lipped about casualties among innocent villagers. Journalists and human rights workers are effectively barred from entering the region. But in April, photographer Asim Rafiqui managed to sneak in by posing as a local businessman.

With no base of support in the area, the Pakistani army (mostly ethnically distinct from the Pashtuns of Waziristan) has been attempting to enlist the support of local tribes and battling those who don’t cooperate. Tribal jirgas, or councils, that comply with the army are rewarded with development aid and spared from bombardment. Other tribal leaders see the conflict as a means to turn the wrath of the army on rival tribes. In any case, lashkars—tribal posses—have ransacked scores of villages, vowing to capture or kill those suspected of cooperating with Al Qaeda. Tradition, however, forbids a host to turn over a guest to an enemy without a fight. And Waziris are even being asked to betray blood relations, although family ties extend far deeper than national loyalty.

In pitting his army against his people, Musharraf risks losing his tenuous hold on power by energizing the very Islamic fundamentalists he seeks to crush. Muslims consider soldiers killed in combat to be martyrs. But many of the tribesmen battling the army are former mujahideen, who, in the 1980s, were actively recruited by Pakistan and the United States to resist the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and support the Taliban. They came from all over Central Asia and settled in the tribal regions. They married, had children, and became woven into the local culture. To many Pakistanis, who don’t understand the about-face of the Musharraf government, it is not the soldiers who are martyrs, but the Waziris fighting them. “America is a wolf at our door,” said retired Lt. Gen. Hamid Gul, a fundamentalist Muslim. “Pakistan throws it crumbs so it does not attack our house. South Waziristan is a crumb. But the people know defenders of the tribal areas are defending their country. Are they terrorists, and the attackers good boys? No. The people don’t believe this.”

Pakistanis are all too cognizant that it is at America’s bidding that Musharraf, his army, and the lashkars of Waziristan carry out this campaign. Any resentment it causes will inevitably flow back up that chain.

Consider again Mir Abbas Khan, in the photo on the opposite page. Look at his eyes, his ruined home, and back to his eyes—full of fear and hurt, but mostly rage.