Photo: <a href="mailto: raphael@wraphael.demon.co.uk">Raphael Schutzer-Weissmann</a>

IN THE WINTER OF 2001, after American fighter planes destroyed a warehouse behind their home in an Afghan village, Fatima Abdulbaqi and her husband, Khalid Alasmar, packed their seven children into a white Toyota Corolla and fled for their lives. The U.S. Air Force was dropping bombs on the mountain roads that the family took to the Pakistani border, and at one point, the way was blocked by burning cars and trucks. Alasmar veered off into a ravine. A plane homed in on the Corolla, and, as the family bolted from the car, bombs fell within a few feet of them. But the worst part of the journey came after they reached Islamabad and the promise of safety.

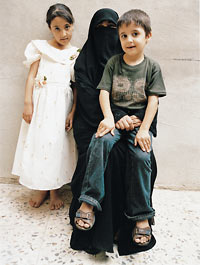

As she recounts what happened next, Abdulbaqi, who is 31, sits with her black-stockinged feet pressed close together beneath the hem of her burka. Her eyes are large and expressive above the veil that covers her nose and mouth. She pulls at the blue embroidered sleeve under the burka and speaks in long and heated bursts of Arabic; the translator has to break in periodically to keep up.

Abdulbaqi explains that her husband, who is Jordanian, had come to Afghanistan in 1986 to join the guerrilla war against the Soviets; she’d met him at a medical clinic run by her parents, and they had lived in Afghanistan and Pakistan for 14 years before deciding to leave the region for good. In Islamabad, they had found a Libyan charity that was arranging flights to Jordan, where Alasmar’s family still lived. But the day before they were scheduled to leave, Abdulbaqi got a call from her husband on his cell phone. He’d gone out to buy presents for his relatives, and the Pakistani police had picked him up. He told Abdulbaqi to leave without him. “I wasn’t worried, because I knew Khalid had done nothing wrong,” Abdulbaqi says. She and the children flew to Libya, and for four months, they waited in a small hotel room in Tripoli. Daily calls to Pakistan yielded empty assurances—”next week he’ll be released, next week, they kept saying,” she recalls.

Desperate for money, Abdulbaqi sold the gold bracelets her parents—who had been killed by a bomb during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan—had given her when she was a child. Then she sold her wedding ring. In late summer 2002, she and the children traveled on to Jordan and moved in with Alasmar’s brother and his family, whom Abdulbaqi had never met. Seven months after Alasmar’s disappearance, she finally got a letter from her husband. It was postmarked Guantanamo Bay.

The Bush administration has never wavered in its assertion that Alasmar and the estimated 550 other detainees currently being held at the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo are enemy combatants—devoted, as Vice President Dick Cheney put it in 2002, to “killing millions of Americans”—who are beyond the reach of U.S. courts. To extract information from the detainees, interrogators have used techniques that the Red Cross says are “tantamount to torture.”

Yet in recent months, the claim that the detainees represented either a significant threat to the United States or a key intelligence asset has rapidly unraveled, with military and intelligence officials publicly saying that, at most, a couple of dozen of the hundreds of prisoners are Al Qaeda operatives or other militants with valuable information. In response, the administration has broadened its claims, arguing that it has the right to indefinitely hold anyone, from an Al Qaeda informer to a “little old lady in Switzerland,” as one government lawyer put it at a recent hearing, if she unwittingly wrote a check to a terrorist group masquerading as a charity.

But amid the wrangling over the detainees’ status, one group of people has rarely been heard from—the prisoners’ families. A few of them live in countries, such as Britain, France, and Australia, that have found lawyers for their detained citizens. But the majority have been people like Fatima Abdulbaqi and her children—Middle Eastern families of modest means who for three years now have been waiting to tell someone, anyone, their stories.

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH IS A TALL, rangy Brit who came to the United States in 1978, at the age of 19, to go to college and fight to end the death penalty. “I was sure it would only take a year or two,” he says with a grimace. Over the next two decades, Stafford Smith helped represent more than 300 clients charged with capital murder, only one of whom was sentenced to death at trial. (That verdict was later overturned on appeal.) For most of that time, Stafford Smith paid himself $18,000 a year. In 2002, the legal isolation of the Guantanamo detainees moved him to take up their cause. “The lesson I learned in 20 years of representing poor black people in the South is that no one knows where to go for help,” he says. “Who could the blokes in Guantanamo call? They had no one.”

Since the Bush administration has not allowed lawyers to interview the detainees—or even to learn their names—Stafford Smith’s first challenge was to find out who his clients might be. So last spring, he began traveling to the Middle East in search of the detainees’ families. He wanted to hear their accounts of how their husbands, sons, or brothers had been seized, and to ask for authorization to represent them or connect them with other lawyers. He started in Yemen, taking out an ad in the country’s largest newspaper. Responses poured in, and 31 families came to talk to him over three days. It was the first time anyone had asked them about their detained relatives. Stafford Smith’s second trip was to Bahrain, where he gathered statements from 27 families; his third took him to Amman, Jordan, where he met Fatima Abdulbaqi.

To interview Abdulbaqi, he drove an hour north of Amman to Irbid, a sprawling city of almost 300,000. The narrow lanes off Irbid’s main road are pitted and dusty, and a half-dozen goats grazed next to the main gas station. On a corner near the house where Abdulbaqi and her family live, a man and a boy spun rounds of flat bread on a wheel. Five of Abdulbaqi’s children sat with their mother while Stafford Smith talked with her. One of her daughters, who is 13, helped translate during the four-hour interview.

In all, Stafford Smith has talked to about 65 family members of detainees. Most insist their relatives were innocent travelers or had gone to Afghanistan on humanitarian missions. Such claims aren’t always convincing; still, Stafford Smith points out, two-thirds of the detainees whose families he interviewed were actually in Pakistan—not on the Afghan battlefield—right before they disappeared. “Either they were in Pakistan all along, or they had just jumped the border to Afghanistan when they were seized,” he says. “I can say fairly confidently that these people didn’t have time to do much of anything against the Americans.”

U.S. officials relied heavily on allied security forces, especially the Pakistani authorities, to find alleged militants; some prisoners have reported that the Americans paid $5,000 for each detainee turned over to them. “There were a lot of complaints about the intelligence behind the determinations about who was going to Guantanamo,” says John Sifton, the lead Afghanistan researcher for Human Rights Watch. “They were sending a lot of nonmilitants and riffraff rather than higher-level people.”

Khalid Alasmar certainly did not fit the profile of an Al Qaeda operative—or even an angry young man eager to battle the Americans. The 40-year-old may have aroused suspicion because he had once fought the Soviets. But Fatima Abdulbaqi says that she and her husband saw the Taliban’s war with America differently than the fight against the Soviet invasion. “This was a war for power,” she says. “Khalid wanted nothing to do with it. He said it was not for God.”

Over the last three years, the Bush administration has quietly released about 200 of the 750 prisoners originally held at the base. But it has continued to assert its right to disclose nothing about the remaining 550, and to review their status only in military tribunals that lack many elements of due process. Most of the detainees still have no way of fighting those procedures: Stafford Smith and other lawyers are lining up legal representation for Khalid Alasmar and other detainees, but more than 450 of the men held at Guantanamo are still unrepresented.

In her brother-in-law’s modest home, Abdulbaqi observed Ramadan without her husband for the third time last fall. Before he was seized, Alasmar supported the family by selling herbs and honey. Now Abdulbaqi and the children subsist on money sent by friends from their mosque in Pakistan. “We are living on donations,” she says with a mix of gratitude and bitterness. Her youngest son peeks around the cotton curtain that separates the neatly decorated front room, where visitors are received, from the kitchen and back rooms, where the linoleum floor is cracked and there is little furniture. Abdulbaqi gets up to fetch a glass of juice. The boy was two months old when his father was arrested, she notes, and he constantly asks for a man he’d never really known. “He sees an old burned-out car and he asks me, ‘Is that Guantanamo? Is my father there?'”