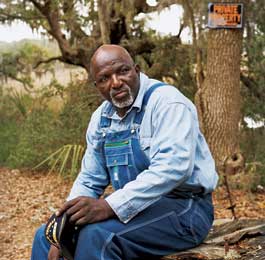

Photo: Sarah Kehoe

the land had been in Roges Brown’s family since 1882, all of 23 acres on the South Carolina coast, reverted now to oaks, magnolias, Spanish moss. Brown had played there as a child more than a half-century before. He had cleared the brush, gardened, gone crabbing down in the marsh. He knew there were no taxes owed on the land, nor any liens against it, and so he couldn’t understand why, at the Charleston County Courthouse, the land was being auctioned off like an abandoned car. All he could think was that it had to have something to do with the array of white lawyers and judges he’d encountered up to this point. “Everything you have, they take from you—just take it,” he thought. A glowering, 64-year-old Vietnam vet, he ended up appearing at the auction in full camouflage, “ranting and raving,” his lawyer remembers, “saying someone needed to die.” When the winning bid was submitted by a black man—his own nephew, no less—Brown was stunned. He wandered Charleston for a long time afterward, “just thinking, ‘search and destroy, search and destroy.'” Then he started writing letters to every public official he could think of, and finally he walked into the Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation in Charleston, where he told the story first to managing attorney Willie Heyward, and, much later, to me.

In short, as Heyward explains it, Brown had fallen victim to the “heirs’ property” conundrum that afflicts tens of thousands of people throughout the South, many of them descendants of slaves who bought plantation land after the Civil War. Through Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, black landowners tended to stay away from the courts and rarely put their wills through the legal system; without those official filings, title dispersed over time among all of an original owner’s descendants. Fractured ownership isn’t generally a problem unless the land becomes valuable—at which point someone typically discovers a provision in the law allowing any heir to file suit for his cut at any time. An auction is a common result, and developers, knowing that auctions mean deals, have been known to recruit an heir to file suit against his family, or to buy the heir’s share outright and file suit themselves. They appear at auction, as one observer puts it, “rubbing their hands and licking their lips.”

It has happened with particular frequency in Charleston County, where the coast is lined with old plantations and as many as 2,000 parcels of heirs’ property. Heyward can remember when few cared to be out there with the mosquitoes. Now, he says, “everyone wants to live by the marsh. Everyone wants to be by the birds and be secluded.” But as property has increased in value, black owners’ hold on it has loosened. Heyward travels the coast, informing owners on how the game is played and how they might solidify their ownership; he uses Brown’s odyssey as a case study of what can happen when a family ends up in court. “All you’ve got to do is turn one heir,” Heyward says, “and everyone loses.” Or almost everyone.

He and Brown took me for a tour of the land, a forest just a few miles from one of the state’s most prestigious golf courses. Heyward pointed beyond the marsh to two oak-covered islands (“That’s the ultimate in seclusion there”) and to the deep water that would allow yachts to dock at their owners’ doorsteps. “Believe me,” he said, “it’s an expensive piece of property.”

Brown confesses it was he, years ago, who first expressed interest in selling. When his nephew, Ben Smith, came forward offering to look into the matter, Brown and several other family members agreed to let him, even though Smith was not in line to inherit. Smith spoke with a woman whose grass he mowed, a realtor named Terryeabrook, whose Space Co. advertises itself as “Charleston’s only full service, African-American real estate company.” She in turn got in touch with a firm called Landmark Properties Inc., whose president was Melissa Seabrook. (According to Terry Seabrook, the two are not related. There is no current listing for Landmark Properties in Charleston; the attorney named as the firm’s representative in filings with the state of South Carolina, Ronald Richter, did not return Mother Jones’ phone calls.) Brown and other family members seem to have been ready to accept Landmark’s offer of $550,000, but a condition of the sale was a clear title. Hoping for a quick resolution, Brown and his siblings agreed to file the suit. When, in the course of the proceedings, the land was reappraised at nearly $2 million, Brown and six other heirs broke with Smith, and the court nullified thyeabrook deal. Judge Roger M. Young ordered the land placed on the market, and when after six months the property failed to sell, he set a date for it to be auctioned.

The day of the auction, August 21, 2002, there may have been more lawyers present than family members. As for bidders, there were only two, and one was Ben Smith, who seemed to have found someone to back his bid. (He “may have teamed with some other investors, I don’t know,” his lawyer told me.) Smith quickly won the land for $500,000, a quarter of its appraised worth.

The money arrived three years after the suit was filed. The suit itself had had the effect of a dinner bell, and so after the lawyers took their fees, some 70 heirs reached in for their share. Among them was an ancient woman from New York who, contrary to common belief, had never divorced the heir she’d married 75 years before. Her share was $34,000. Most of the rest had to content themselves with significantly less. Even long after the case was settled, there were letters coming into the file from heirs wanting a cut, claiming that relatives (“whom I know quite well”) had never notified them of the sale.

Roges Brown’s interest in the land was determined to be .74 of 1 percent, or $3,272.97, not much more than he had paid in legal fees. Ben Smith, who did not qualify as an heir at all, got about the same by way of compensation for trying to find a buyer for the land. Everything had gone according to proper procedure, Brown’s lawyer, Edward Pritchard Jr., told me, and he couldn’t understand why his client was so angry. “A lot of people,” he said, “just don’t understand how the law works.”

When Brown went finally to a lawyer who charged him nothing, Heyward agreed that the family had not understood the law, but he also knew the law had not looked out for the family. Changes that would protect heirs’ property—such as mandatory mediation—depend on political clout, which in the case of real estate laws comes mostly from developers. Charleston, notes Heyward, remains a culture that has changed very little. “They pride themselves on not changing,” he says. “That’s the tourist attraction. People come to Charleston to see things the way they were, not for progress.”

A year after buying the land, Smith flipped it to a developer from Pinehurst, North Carolina, for double what he’d paid at the auction—$1 million. Terry Seabrook brokered the deal. Plots next door to the property were recently selling for $200,000 an acre. For a time Smith lived directly across the street, in a gated golfing community called Hope Plantation. I wanted to ask him where he had gotten the money for the auction, but Brown said you can’t go into Hope Plantation, not even if you’re family. When I got Smith on the phone, he didn’t want to talk, and said in a cold, flat voice, “If you put my name in the paper…I’m going to have to shoot someone. Do you understand?” His name was going in, I told him, at which point he began to shout: “If you do that, sir, I’m coming to find your ass, and I’m going to put a bullet in your fucking head!” Then he slammed down the phone and returned to the solitude of his wealth.