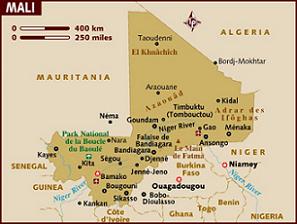

Eight years ago, 31-year-old teacher Jack Carneal moved with his wife and young son to Bougouni, Mali. While his wife was busy researching rural education, Jack became immersed in the region’s home-grown musical culture, buying up hand-copied cassettes and recording live street performances. Upon returning to the states, his handing out of Mali mix-tapes for friends grew into Yaala Yaala Records, an imprint of Chicago’s Drag City dedicated to bringing Malian music to more listeners. We exchanged e-mails this week.

Eight years ago, 31-year-old teacher Jack Carneal moved with his wife and young son to Bougouni, Mali. While his wife was busy researching rural education, Jack became immersed in the region’s home-grown musical culture, buying up hand-copied cassettes and recording live street performances. Upon returning to the states, his handing out of Mali mix-tapes for friends grew into Yaala Yaala Records, an imprint of Chicago’s Drag City dedicated to bringing Malian music to more listeners. We exchanged e-mails this week.

What was daily life like in your village in Mali?

It was based on domestic rituals: hanging out with neighbors, going to the market, taking naps, preparing meals. Our son was only 2 when we were there so much of our lives—the joys and stresses—revolved around our being relatively new parents, and in such a dynamic environment, to boot. On the main it was fantastic but we lived in a cinderblock house with a tin roof, and when daytime temps got up to 115 we often longed to be elsewhere.

How difficult was the process of tracking down musicians, getting their permission to record them, and, well, getting a good take?

The ‘getting a good take’ part was so simple as to be nonexistent. They played, I recorded. The musicians, in many cases, would’ve been performing regardless of whether or not I was there, and in the other cases I’d met the musicians and hung out with them a little bit before recording them.

I was, coincidentally, obsessing over Malian duo Amadou & Mariam’s Dimanche a Bamako when I happened upon the Yaala Yaala releases, but then I saw on your label’s site that they’re dismissed as music for “export”, and not really part of the local musical culture. I had thought I recognized some similar musical motifs, but am I just a naïve westerner thinking French fries make me an expert on French cuisine?

I love Amadou and Miriam, actually, but yes, they were never once mentioned out in Bougouni. There is a scale that a lot of Malian and West African music is based on and a similar long descending melody line in some tunes as well, ergo the audible similarity.

Has it been frustrating negotiating the restrictions and legalities of putting out actual releases, and dealing with the catch-22 of accusations of profiteering from the music of poor Africans?

Not too much, really. All agreements on BY were personal, between the musicians and I. I can be a bit prickly about these accusations, though. I’ve got a full-time job as a teacher and am not running this label in order that I may retire to Mustique. I do this because I love Malian music and recognized that the coolest Malian music was not being represented in the ultra-commercially oriented world music market. I have no intention of profiting. I’ll be happy to make my costs back. In any case all profits that might be accrued are going into the Yaala Yaala Rural Musician’s Collective, a fund I’ve started that will be disbursed when there’s something to disburse.

Do you think people who have expressed concerns about the financial side of Yaala Yaala are merely curious about how things were arranged, or is something more nefarious going on, like a potentially racist conception of the musicians as “primitive” and thus easily exploitable?

Do you think people who have expressed concerns about the financial side of Yaala Yaala are merely curious about how things were arranged, or is something more nefarious going on, like a potentially racist conception of the musicians as “primitive” and thus easily exploitable?

The latter seems possible if not likely. I took great issue with Clive Barker’s absolutely pretentious criticism of our guerilla take on releasing music in The Wire and thought it was patronizing as heck, even as he accused me of the same thing! I lived there, after all, among Bougounians and only Bougounians (there was no expat community out there, with gin parties at the ambassador’s, etc) and suddenly he’s the great white savior tearing down the greedy American for exploiting the poor, helpless Malians. Yes, I think there’s a tinge of post-colonial guilt there from the old Limey.

On Bougouni Yaalali, I’m not sure if it’s the background noise or the lack of song titles, but there’s a kind of dreamlike quality, like floating from one musical scene to another, down a dusty street. Sometimes I’m not even sure what instrument is being played—is that a steel drum on Track 4?—but the feeling of being there is remarkable. Was this a goal, not only to show the world these talented musicians, but to give us a sense of place?

It’s a balaphon, a West African xylophone, mic’ed and pumped through a horn speaker! Nothing was planned beforehand. However, I am pleased that people are responding to it as an auditory documentary of a very particular place: rural southeastern Mali, a region where a lot of the music we listen to today has its deepest roots.

You’re saying you see a direct line from Malian music to, uh, Fall Out Boy?

In a freaky way, YES! We’re working on our next round of releases, some of which we hope will be Malian hunter’s music. According to ethnomusicologist Eric Charry, this could be one of the oldest forms of ritual music in existence. And lo and behold, most of it is 4/4 with very rock-like tempos and inflections. It’s incredibly great music, and though I’m not claiming Fall Out Boy has listened to Yoro Sidibe, I believe that this very well could be as much a forbear of southern blues traditions as anything. Which of course became rock and roll, baybee!

Yaala Yaala Records’ home page is here; read a longer interview with Carneal in the Washington City Paper here.

MP3s from the Drag City site: Pekos/Yoro Diallo excerpt; Bougouni Yaalali excerpt; Doudala Dembele excerpt.

Update: Weirdly enough, at the exact time I was working on posting this interview, Idolator put up a piece that (in addition to misspelling the label’s name) continued the accusations of “chauvinistic bootlegging” towards Carneal and Yaala Yaala, while giving a glowing review to the Pekos/Yoro Diallo release. I’ve asked Carneal if he’d like to make a response, which I’ll post here if he does so.

Update #2: Carneal got in touch to reiterate that “any and all profits from Yaala Yaala will go to our Rural Musician’s Collective fund where it will be held and disbursed annually. …I align myself firmly with the Sublime Frequencies guys: if we weren’t putting out this music no one would hear it. That’s reason enough to do it. If money is made it will go to the right people.”