For primary voters who lean toward the left of the Democratic Party, the candidacy of John Edwards has presented a series of impossible contradictions—the latest being the fact that the further down he dips in polls and in fundraising numbers, the more he starts saying the kinds of things they have been waiting to hear from a mainstream Democrat for twenty years or more. At a campaign stop in New Hampshire on Saturday, Edwards told an overflow crowd:

I think there are powerful interests in Washington DC…. The entire system is rigged, and it’s rigged against you…. From insurance companies to drug companies to oil companies, those people run this country now…. And I think you got to take them on and beat them, I don’t think you can sit at a table and negotiate with them. The idea that they are going to voluntarily give away their power… that will never happen…. They have billions of dollars invested in making sure there is no change, that the system continues exactly like it’s continuing today.

At a stop in Iowa a few days earlier, Edwards took his populist rhetoric a step further, characterizing the attention to “silly frivolous nothing stuff” (presumably including his $400 haircuts and his former hedge fund salary) as a backlash—apparently, with the support of the mainstream media—by the rich and powerful, especially corporations, who are threatened by his campaign:

This stuff’s not an accident. Nobody in this room should think this is an accident. You know, I’m out there speaking up for universal healthcare, ending this war in Iraq, speaking up for the poor. They want to shut me up. That’s what this is about. Let’s distract from people who don’t have health care coverage. Let’s distract from people who can’t feed their children…. Let’s talk about this silly frivolous nothing stuff so that America won’t pay attention. They will never silence me. Never. If we don’t stand up to these people, if we don’t fight ‘em, if we don’t beat them, they’re going to continue to control this country. They’re going to control the media. They’re going to control what’s being said. They do not want to hear us talking about health care for everybody. They don’t want to hear us talking about a fair tax system. You think these people who make $100 million a year, you think they want to pay their fair share of taxes? That’s what they hire all those lobbyists for in Washington, DC. They hate listening to people like me.

These are words to strike hope in the hearts of progressive Democrats. But are they just words? Beyond the question of whether “they” are attacking Edwards, does his campaign really present a threat to the powerful interests that do indeed, as he says, “run this country now”?

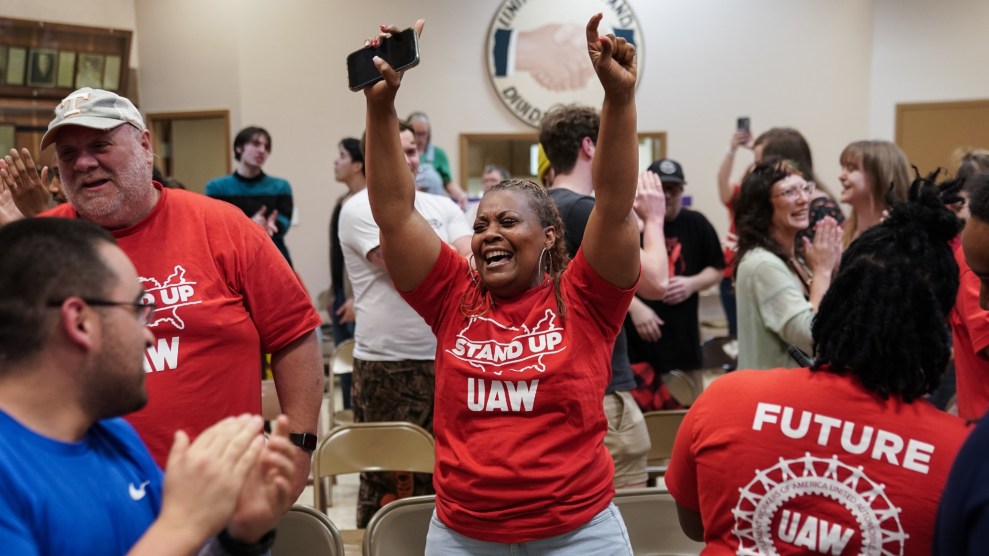

From the start of his campaign, Edwards, considered one of only three viable candidates for the nomination, has positioned himself slightly to the left of frontrunners Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, especially on questions of economic justice. At the Democratic National Committee’s winter meeting in 2007, the first major public forum for 2008 presidential candidates, “Edwards drew a rousing reception,” the Washington Post reported, “with a sharp attack on Bush’s plan to send more troops to Iraq and a populist appeal for Democrats to return to their roots as defenders of the union workers, the poor and struggling middle-class families. ‘Brothers and sisters, in times like these, we don’t need to redefine the Democratic Party,’ he said. ‘We need to reclaim the Democratic Party.'”

Five weeks earlier, Edwards had announced his candidacy in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, surrounded by hurricane survivors who had been not only exploited by conservatives, but also largely ignored by most liberals. That day, Edwards finally highlighted poverty—an issue that had been so conspicuously absent from the Democratic Party platform, both in the failed 2004 presidential campaign and the triumphant 2006 mid-term elections.

Progressive voters can also find encouragement in the assessments of the mainstream press, which depict Edwards as the Southern New Democrat who left the fold of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council to take up a populist cause. After a day on the New Hampshire campaign trail with Edwards in February, ABC’s Terry Moran declared, “He’s different this time around. In 2004, when he was a relative unknown, Edwards was a cheerful moderate populist. Now, in what some critics call a convenient conversion to woo liberal Democrats, Edwards is tougher, staking out positions on health care, national security, and the environment much further to the left than he advocated in 2004.”

Convenient or not, the idea of Edwards’ “conversion” is buoyed not only by his own rhetoric but also by attacks from conservative critics. “He is a redistributionist, another word for socialist,” Cal Thomas wrote recently in USA Today. “His populist jargon is nothing but class warfare, the 2007 version.”

And yet this same John Edwards can also come off as a slick lawyer, who has plenty of stories to tell about his legal victories defending Main Street Americans injured by uncaring or nefarious corporations and health care providers, but rarely mentions the fact that these multimillion dollar civil suits also made Edwards himself a very rich man. His assets total some $30 million, and while the senator likes to talk about his days of poverty and hardship, he did not hesitate to build an ostentatious 28,000 square-foot mansion in North Carolina. In between his two presidential campaigns, he also worked for a hedge fund that engaged in the kinds of practices he now decries, and suggested, in an AP interview, that he had done so largely “to learn about financial markets and their relationship to poverty”—although “making money was a good thing, too.”

Most troubling of all is evidence that, during this same period, he used an anti-poverty foundation to fund travel, staff, consultants, and other expenses that advanced his own political career.

It’s true that the media seems to have a double standard when it comes to Edwards, largely because of his very willingness to talk about the poor. Jeff Cohen, founder of the media watchdog group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, points out that “we’ve been shown aerial pictures of Edwards’ mansion in North Carolina, but not of the mansions of the other well-off candidates” and “we’ve heard so much about Edwards’ connection to one Wall Street firm, but relatively little about the fact that other candidates, including Democrats, are so heavily funded by Wall Street interests…. You see, those other pols aren’t hypocrites: They don’t lecture about poverty.”

Edwards’ wealth alone may not disqualify him as a defender of the poor, any more than it did Franklin Roosevelt or Bobby Kennedy, two of the wealthiest men ever to run for president. But it adds fuel to the essential question: Does Edwards present a real challenge to the system that creates such massive inequities to begin with? Is he willing to help the poor even at the expense of people in his income bracket, and the corporate entities that helped make them rich? Former Labor Secretary Robert Reich told the New York Times: “Rhetorically, if you’re calling Edwards an economic populist, it’s true he cares a lot about the poor. He evinces a lot of concern for the middle class and middle-class anxieties. But he’s not in any way attacking the rich or corporations. He is not explaining one fundamental fact of modern economic life, which is that the very rich have all the money.”

During his single term in the Senate, Edwards was less corporate-friendly than the Clinton New Democrats of the Democratic Leadership Council, but not by all that much—and no amount of wishful thinking will produce evidence of a radical transformation on Edwards’s part. Still, he has indeed moved to the left on several issues—in some cases, far enough left to distinguish himself from Clinton and Obama, who can also be found playing so-called populist cards when it seems politically expedient to do so.

Edwards’ poverty reduction program is a mix of ideas advocated over the years by the party centrists, with a few imaginative touches and some stirring rhetoric. In one way or another, these are all good ideas. They have been tried off and on since the New Deal with varying degrees of success. Edwards currently proposes raising the minimum wage to $9.50 an hour, along with a somewhat vague sounding jobs program for the unemployed that would create a million “stepping stone jobs for workers who take responsibility”—minimum wage jobs lasting up to 12 months, and in return, “workers must show up and work hard, stay off drugs, not commit any crimes, and pay child support.” (Dennis Kucinich, in contrast, wants to put people without jobs to work rebuilding America’s crumbling public infrastructure—bridges, tunnels, roads—at a time when many politicians in both parties are desiring to sell them off; his program would put people of New Orleans to work rebuilding their own city and its water defenses.)

Whether Edwards’ leftward turn is sincere or merely shrewd—or, as is most likely the case, both—his rhetoric in defense of America’s poor nevertheless stands to have a much-needed and long-overdue impact on the presidential race. After accompanying Edwards on one of his many trips to New Orleans, Matt Bai wrote in the New York Times Magazine: “The significance of what Edwards is saying… goes well beyond messaging and tactics. As the first candidate of the post-Bill Clinton, postindustrial era to lay out an ambitious antipoverty plan, he may force Democrats to contemplate difficult questions that they haven’t debated in decades—starting with what they’ve learned about poverty since Johnson and Kennedy’s time, and what, exactly, they’re willing to do about it.”